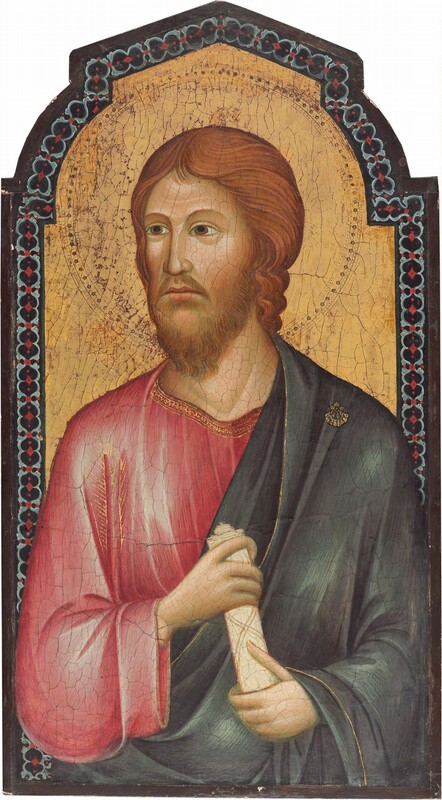

Saint James Major

c. 1310

Grifo di Tancredi

Painter, Italian, active 1271 - 1303 (or possibly 1328)

This image, along with Saint Peter and Christ Blessing, originally occupied a single panel. They and two others—one now in a museum in France, the other lost—were cut from the same altarpiece. It would have been an imposing work with triangular gables (see Reconstruction). The considerable dimensions and elaborate ornamental decoration incised on the gold ground suggest that this altarpiece must have been a commission of some importance. However, the iconographic conventions and technical features (execution on a single panel) are of an archaizing type, which indicates that whoever ordered this painting wanted an artist like Grifo di Tancredi, who worked in a traditional style.

The young Giotto’s influence was being felt in Florence at that time, but Grifo remained firmly in the orbit of the great Sienese master Cimabue and the artists of Grifo’s own generation. For these artists, producing the illusion of three-dimensional space was not of prime importance, and the influence of Eastern or Byzantine art was key. Although Saint James wears the shell-shaped pilgrimage badge associated with the saint in the West, he is also presented holding his Byzantine attribute: a scroll.

Until the late 1980s, Grifo’s identity was unknown. His works had been mostly collected in a group of paintings related to the San Gaggio altarpiece (Galleria dell’Accademia in Florence) assigned to the “Master of San Gaggio,” but a single, difficult-to-read inscription on one of these paintings was deciphered and Grifo was saved from anonymity.

Artwork overview

-

Medium

tempera on panel

-

Credit Line

-

Dimensions

painted surface (top of gilding): 62.2 × 34.8 cm (24 1/2 × 13 11/16 in.)

painted surface (including painted border): 64.8 × 34.8 cm (25 1/2 × 13 11/16 in.)

overall: 66.7 × 36.7 × 1.2 cm (26 1/4 × 14 7/16 × 1/2 in.) -

Accession Number

1937.1.2.c

Associated Artworks

Saint Peter

Grifo di Tancredi

1310

Christ Blessing

Grifo di Tancredi

1310

More About this Artwork

Artwork history & notes

Provenance

By 1808 in the collection of Alexis-François Artaud de Montor [1772-1849], Paris, who probably purchased the panels during one of his several periods of residence in Italy;[1] (his estate sale, Seigneur and Schroth at Hotel des Ventes Mobilières, Paris, 16-17 January 1851, nos. 35, 36, and 39 [with 1937.1.2.a and .b, as by Margaritone d’Arezzo]); Julien Gréau [1810-1895], Troyes; by inheritance to his daughter, Marie, comtesse Bertrand de Broussillion, Paris;[2] purchased September 1919 by (Duveen Brothers, Inc., Paris, New York, and London);[3] Carl W. Hamilton [1886-1967], New York, by 1920;[4] returned to (Duveen Brothers, Inc.); sold 15 December 1936 to The A.W. Mellon Educational and Charitable Trust, Pittsburgh;[5] gift 1937 to NGA.

[1] On Artaud de Montor, apart from the unpublished doctoral dissertation of Roland Beyer for the University of Strasbourg in 1978, see Jacques Perot, "Canova et les diplomates français à Rome. François Cacault et Alexis Artaud de Montor,” Bullettin de la Société de l’Histoire de l’Art français (1980): 219- 233, and Andrea Staderini, “Un contesto per la collezione di primitivi di Alexis - François Artaud de Montor (1772-1849),” Proporzioni. Annali della Fondazione Roberto Longhi 5 (2004): 23-62.

[2] This information on the post-Artaud de Montor provenance of the work was gleaned at the time Duveen Brothers, Inc., purchased the three panels. See the Duveen prospectus, in NGA curatorial files; Edward Fowles, Memories of Duveen Brothers, London, 1976: 116.

[3] Fowles 1976, 116; Duveen Brothers Records, accession number 960015, Research Library, Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles: reel 85, box 230, folder 25, and reel 422. The Duveen record indicates that they purchased the painting in Paris from Hilaire Gréau, a son of Julien Gréau.

[4] The three panels were exhibited as “lent by Carl W. Hamilton” in the New York exhibition in 1920. Fern Rusk Shapley (Catalogue of the Italian Paintings, 2 vols., Washington, D.C., 1979: 1:134) also states that they were formerly in the Hamilton collection, and it is reported that “the Cimabue altarpiece was seen in Hamilton’s New York apartment” by 1920 (see Colin Simpson, Artfull Partners. Bernard Berenson and Joseph Duveen, New York, 1986: 199). However, this and other pictures had actually been given to Hamilton on credit by Duveen Brothers (see Meryle Secrest, Duveen. A Life in Art, New York, 2004: 422) and were probably returned to the dealers by 1924, when they were shown as "lent anonymously" at the exhibition of early Italian paintings in American collections held by the Duveen Galleries in New York.

[5] The original bill of sale is in Records of The A.W. Mellon Educational and Charitable Trust, Subject Files, box 2, Gallery Archives, NGA; copy in NGA curatorial files.

Associated Names

Exhibition History

1920

Fiftieth Anniversary Exhibition, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 1920, unnumbered catalogue.

1924

Loan Exhibition of Important Early Italian Paintings in the Possession of Notable American Collectors, Duveen Brothers, New York, 1924, no. 2, as by Giovanni Cimabue (no. 1 in illustrated 1926 version of catalogue).

1935

Exposition de L'Art Italien de Cimabue à Tiepolo, Petit Palais, Paris, 1935, no. 110.

1979

Berenson and the Connoisseurship of Italian Painting, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., 1979, no. 81.

2014

La fortuna dei primitivi: Tesori d’arte dalle collezioni italiane fra Sette e Ottocento [The Fortunes of the Primitives: Artistic Treasures from Italian Collections between the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries], Galleria dell'Accademia, Florence, 2014, no. 79a, repro.

Bibliography

1808

Artaud de Montor, Alexis-François. Considérations sur l’état de la peinture en Italie, dans les quatre siècles qui ont précédé celui de Raphaël: par un membre de l’académie de Cortone. Ouvrage servant de catalogue raisonné à une collection de tableaux des XIIe, XIIIe, XIVe et XVe siècles. Paris, 1808: no. 34.

1811

Artaud de Montor, Alexis-François. Considérations sur l’état de la peinture en Italie, dans les quatre siècles qui ont précédé celui de Raphaël, par un membre de l’Académie de Cortone (Artaud de Montor). Ouvrage servant de catalogue raisonné à une collection de tableaux des XIIe, XIIIe, XIVe et XVe siècles. Paris, 1811: no. 39.

1843

Artaud de Montor, Alexis-François. Peintres primitifs: collection de tableaux rapportée d’Italie. Paris, 1843: no. 39.

1920

Berenson, Bernard. "Italian Paintings." Bulletin of the Metropolitan Museum of Art 15 (1920): 159-160, repro.

Robinson, Edward. "The Fiftieth Anniversary Celebration." Bulletin of the Metropolitan Museum of Art 15 (1920): 75.

Berenson, Bernard. "A Newly Discovered Cimabue." Art in America 8 (1920): 251-271, repro. 250.

Fiftieth Anniversary Exhibition. Loans and Special Features. Exh. cat. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 1920: 8.

1922

Sirén, Osvald. Toskanische Maler im XIII. Jahrhundert. Berlin, 1922: 299-301, pl. 114.

1923

Marle, Raimond van. The Development of the Italian Schools of Painting. 19 vols. The Hague, 1923-1938: 1(1923):476, 574; 5(1925):442, fig. 262.

1924

Vitzthum, Georg Graf, and Wolgang Fritz Volbach. Die Malerei und Plastik des Mittelalters in Italien. Handbuch der Kunstwissenschaft 1. Wildpark-Potsdam, 1924: 249-250.

Offner, Richard. "A Remarkable Exhibition of Italian Paintings." The Arts 5 (1924): 241 (repro.), 244.

Loan Exhibition of Important Early Italian Paintings in the Possession of Notable American Collectors. Exh. cat. Duveen Brothers, New York, 1924: no. 2.

1926

Valentiner, Wilhelm R. A Catalogue of Early Italian Paintings Exhibited at the Duveen Galleries, April to May 1924. New York, 1926: n.p., no. 1, repro.

1927

Toesca, Pietro. Il Medioevo. 2 vols. Storia dell’arte italiana, 1. Turin, 1927: 2:1040 n. 48.

1930

Berenson, Bernard. Studies in Medieval Painting. New Haven, 1930: 17-31, fig. 14.

1931

Fry, Roger. "Mr Berenson on Medieval Painting." The Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs 58, no. 338 (1931): 245.

Venturi, Lionello. Pitture italiane in America. Milan, 1931: no. 8, repro.

1932

Berenson, Bernard. Italian Pictures of the Renaissance: A List of the Principal Artists and Their Works with an Index of Places. Oxford, 1932: 150.

Nicholson, Alfred. Cimabue: A Critical Study. Princeton, 1932: 59.

1933

Venturi, Lionello. Italian Paintings in America. Translated by Countess Vanden Heuvel and Charles Marriott. 3 vols. New York and Milan, 1933: 1:no. 10, repro.

1935

Serra, Luigi. "La mostra dell’antica arte italiana a Parigi: la pittura." Bollettino d’arte 29 (1935-1936): 31, repro. 33.

Salmi, Mario. "Per il completamento di un politico cimabuesco." Rivista d’arte 17 (1935): 113-120, repro. 115.

Muratov, Pavel P., and Jean Chuzeville. La peinture byzantine. Paris, 1935: 143.

Escholier, Raymond, Ugo Ojetti, Paul Jamot, and Paul Valéry. Exposition de l’art italien de Cimabue à Tiepolo. Exh. cat. Musée du Petit Palais. Paris, 1935: 51.

1936

Berenson, Bernard. Pitture italiane del rinascimento: catalogo dei principali artisti e delle loro opere con un indice dei luoghi. Translated by Emilio Cecchi. Milan, 1936: 129.

1937

"The Mellon Gift. A First Official List." Art News 35 (20 March 1937): 15.

1941

Duveen Brothers. Duveen Pictures in Public Collections of America. New York, 1941: no. 5, repro., as by Cimabue.

Preliminary Catalogue of Paintings and Sculpture. National Gallery of Art, Washington, 1941: 41, no. 2, as by Cimabue.

Richter, George Martin. "The New National Gallery in Washington." The Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs 78 (June 1941): 177.

Coletti, Luigi. I Primitivi. 3 vols. Novara, 1941-1947: 1(1941):37.

1942

Book of Illustrations. National Gallery of Art, Washington, 1942: 239, repro. 85, as by Cimabue.

1943

Sinibaldi, Giulia, and Giulia Brunetti, eds. Pittura italiana del Duecento e Trecento: catalogo della mostra giottesca di Firenze del 1937. Exh. cat. Galleria degli Uffizi. Florence, 1943: 277.

1946

Salvini, Roberto. Cimabue. Rome, 1946: 23.

1947

Offner, Richard. A Critical and Historical Corpus of Florentine Painting. The Fourteenth Century. Sec. III, Vol. V: Master of San Martino alla Palma; Assistant of Daddi; Master of the Fabriano Altarpiece. New York, 1947: 216 n. 1.

1948

Longhi, Roberto. "Giudizio sul Duecento." Proporzioni 2 (1948): 19, 47, fig. 37.

Pope-Hennessy, John. "Review of Proporzioni II by Roberto Longhi." The Burlington Magazine 90 (1948): 360.

1949

Paintings and Sculpture from the Mellon Collection. National Gallery of Art, Washington, 1949 (reprinted 1953 and 1958): 5, repro.

Garrison, Edward B. Italian Romanesque Panel Painting: An Illustrated Index. Florence, 1949: 172-173, repro.

Carli, Enzo. "Cimabue." In Enciclopedia Cattolica. 12 vols. Vatican City, 1949-1954: 3(1949):1614, repro.

1951

Einstein, Lewis. Looking at Italian Pictures in the National Gallery of Art. Washington, 1951: 16-18, repro., as by Cimabue.

Galetti, Ugo, and Ettore Camesasca. Enciclopedia della pittura italiana. 3 vols. Milan, 1951: 1:642; 2:1486.

1955

Ragghianti, Carlo Ludovico. Pittura del Dugento a Firenze. Florence, 1955: 127, fig. 186.

1956

Longhi, Roberto. "Giudizio sul Duecento (1948)." In Edizione delle opere complete di Roberto Longhi. 14 vols. Florence, 1956-2000: 7(1974):14, 44, pl. 36.

Samek Ludovici, Sergio. Cimabue. Milan, 1956: 42-44, 48.

Laclotte, Michel. De Giotto à Bellini: les primitifs italiens dans les musées de France. Exh. cat. Musée de l’Orangerie, Paris, 1956: 15.

1958

Salvini, Roberto. "Cimabue." In Enciclopedia Universale dell’Arte. Edited by Istituto per la collaborazione culturale. 15 vols. Florence, 1958-1967: 3(1960):473.

Marcucci, Luisa. Gallerie nazionali di Firenze. Vol. 1, I dipinti toscani del secolo XIII. Rome, 1958: 56.

1960

Boskovits, Miklós. "Cenni di Pepe (Pepo), detto Cimabue." In Dizionario biografico degli italiani. Edited by Alberto Maria Ghisalberti. 82+ vols. Rome, 1960+: 23(1979):542.

Le Musée des Beaux-Arts de Chambéry. Chambéry, 1960: n.p., fig. 15.

1962

Hager, Hellmut. Die Anfänge des italienischen Altarbildes. Untersuchungen zur Entstehungsgechichte des toskanischen Hochaltarretabels. Munich, 1962: 111-112.

1963

Walker, John. National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. New York, 1963 (reprinted 1964 in French, German, and Spanish): 297, repro.

Berenson, Bernard. Italian Pictures of the Renaissance. Florentine School. 2 vols. London, 1963: 1:50, fig. 4.

Longhi, Roberto. "In traccia di alcuni anonimi trecentisti." Paragone 14 (1963): 10.

1964

Previtali, Giovanni. La fortuna dei primitivi: dal Vasari ai neoclassici. Turin, 1964: 232.

1965

Summary Catalogue of European Paintings and Sculpture. National Gallery of Art, Washington, 1965: 28.

1967

Salmi, Mario. "La donazione Contini Bonacossi." Bollettino d’arte 52 (1967): 223, 231 n. 1.

Previtali, Giovanni. Giotto e la sua bottega. Milan, 1967: 26.

1968

National Gallery of Art. European Paintings and Sculpture, Illustrations. Washington, 1968: 21, repro.

1969

Volpe, Carlo. "La formazione di Giotto nella cultura di Assisi." In Giotto e i giotteschi in Assisi. Rome, 1969: 38.

1972

Fredericksen, Burton B., and Federico Zeri. Census of Pre-Nineteenth Century Italian Paintings in North American Public Collections. Cambridge, Mass., 1972: 54, 403, 440, 645.

1974

Previtali, Giovanni. Giotto e la sua bottega. 2nd ed. Milan, 1974: 26.

1975

European Paintings: An Illustrated Summary Catalogue. National Gallery of Art, Washington, 1975: 70, repro., as Attributed to Cimabue.

1976

Fowles, Edward. Memories of Duveen Brothers. London, 1976: 116.

1979

Shapley, Fern Rusk. Catalogue of the Italian Paintings. 2 vols. Washington, 1979: 1:134-135; 2:pl. 94.

1982

Pietralunga, Fra Ludovico da, and Pietro Scarpellini (intro. and comm.). Descrizione della Basilica di S. Francesco e di altri Santuari di Assisi. Treviso, 1982: 416.

1985

European Paintings: An Illustrated Catalogue. National Gallery of Art, Washington, 1985: 90, repro.

1986

Simpson, Colin. Artful Partners: Bernard Berenson and Joseph Duveen. New York, 1986: 199.

Guerrini, Alessandra. "Maestro di San Gaggio." In La Pittura in Italia. Il Duecento e il Trecento. Edited by Enrico Castelnuovo. 2 vols. Milan, 1986: 2:625.

1987

Marques, Luiz. La peinture du Duecento en Italie centrale. Paris, 1987: 202, 286, fig. 253.

1990

Tartuferi, Angelo. La pittura a Firenze nel Duecento. Florence, 1990: 63, 109.

Damian, Véronique, and Jean-Claude Giroud. Peintures florentines. Collections du Musée de Chambéry. Chambéry, 1990: 23, 66-67.

1992

Chiodo, Sonia. "Grifo di Tancredi." In Allgemeines Künstlerlexikon: Die bildenden Künstler aller Zeiten und Völker. Edited by Günter Meissner. 87+ vols. Munich and Leipzig, 1992+: 62(2009):129.

1993

Previtali, Giovanni, and Giovanna Ragionieri. Giotto e la sua bottega. Edited by Alessandro Conti. 3rd ed. Milan, 1993: 36.

Boskovits, Miklós. A Critical and Historical Corpus of Florentine Painting. Sec. I, Vol. I: The Origins of Florentine Painting, 1100–1270. Florence, 1993: 732 n. 1, 809.

1996

"Artaud de Montor, Jean Alex Francis." In The Dictionary of Art. Edited by Jane Turner. 34 vols. New York and London, 1996: 2:514.

1998

Bellosi, Luciano. Cimabue. Edited by Giovanna Ragionieri. 1st ed. Milan, 1998: 287, 289.

Frinta, Mojmír S. Punched Decoration on Late Medieval Panel and Miniature Painting. Prague, 1998: 442, 443.

1999

Bagemihl, Rolf. "Some Thoughts About Grifo di Tancredi of Florence and a Little-Known Panel at Volterra." Arte cristiana 87 (1999): 413-414.

2001

Offner, Richard, Miklós Boskovits, Ada Labriola, and Martina Ingendaay Rodio. A Critical and Historical Corpus of Florentine Painting. The Fourteenth Century. Sec. III, Vol. V: Master of San Martino alla Palma; Assistant of Daddi; Master of the Fabriano Altarpiece. 2nd ed. Florence, 2001: 472 n. 1.

2002

Tartuferi, Angelo. "Grifo di Tancredi." In Dizionario biografico degli italiani. Edited by Alberto Maria Ghisalberti. 82+ vols. Rome, 1960+: 59(2002):398.

2004

Secrest, Meryle. Duveen: A Life in Art. New York, 2004: 422.

Bellosi, Luciano. "La lezione di Giotto." in Storia delle arti in Toscana. Il Trecento. Edited by Max Seidel. Florence, 2004: 96.

Staderini, Andrea. "Un contesto per la collezione di ‘primitivi’ di Alexis-François Artaud de Montor (1772-1849)." Proporzioni 5 (2004): 38.

2005

Leone De Castris, Pierluigi. "Montano d’Arezzo a San Lorenzo." In Le chiese di San Lorenzo e San Domenico: gli ordini mendicanti a Napoli. Edited by Serena Romano and Nicolas Bock. Naples, 2005: 109.

2007

Bellosi, Luciano, and Giovanna Ragionieri. Giotto e la sua eredità: Filippo Rusuti, Pietro Cavallini, Duccio, Giovanni da Rimini, Neri da Rimini, Pietro da Rimini, Simone Martini, Pietro Lorenzetti, Ambrogio Lorenzetti, Matteo Giovannetti, Masso di Banco, Puccio Capanna, Taddeo Gaddi, Giovanni da Milano, Giottino, Giusto de’Menabuoi, Altichiero, Jacopo Avanzi, Jean Pucelle, i Fratelli Limbourg. Florence, 2007: 68, fig. 42.

2014

Tartuferi, Angelo, and Gianluca Tormen. La fortuna dei primitivi: Tesori d’arte dalle collezioni italiane fra Sette e Ottocento. Exh. cat. Galleria dell’Accademia. Florence, 2014: 427-429, repros.

2016

Boskovits, Miklós. Italian Paintings of the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Centuries. The Systematic Catalogue of the National Gallery of Art. Washington, 2016: 177-188, color repro.

Wikidata ID

Q20172973