Look to the Light: A Reflection on Aaron Douglas’s “Into Bondage”

Imagine . . . you are already free. You just don’t know it yet.

This thought always comes to my mind on Juneteenth—a holiday named for a mashup of “June” and “19th.” Each Juneteenth, we celebrate the moment in 1865 when Union soldiers read the Emancipation Proclamation to freed Black people still working on plantations in Texas. This momentous post–Civil War action let over a quarter of a million people know that they were free—and had been, on paper, for two and a half years. On Juneteenth, without fail I wonder, what illusion of bondage could I be trapped in, unaware that I’m already free?

In Into Bondage, Aaron Douglas depicted African people, forced to walk toward their own enslavement in the Americas—a visual echo of atrocities that continued for hundreds of years. In 1862, anticipating the Emancipation Proclamation, slaveholders from Southern states including Louisiana and Mississippi forced more than 150,000 enslaved people to travel on foot to Texas to uphold an antebellum way of life.

Before Juneteenth, news from the warfront was slow to reach Texas. There, planters could continue the practice of chattel slavery, resisting change and progress. The people seen in Douglas’s painting also travel on foot, walking toward the slave ships we see on the water near the horizon line. Just under the ships, a despairing woman lifts her chained arms toward a star in the distant sky.

In creating Into Bondage, Douglas employed his most recognizable painting style and techniques. Richly layered shades of blue, pink, purple, yellow, and green fill the scene. The silhouetted figures are solid blocks of blues and greens, interrupted only by wrist shackles in starkly contrasting pale purple. A circle in the center of the scene ripples outward like sound waves or rings on the surface of water.

Into Bondage debuted on Juneteenth 1936—one of four Douglas paintings that form a mural depicting the journey of African Americans from the transatlantic slave trade to present. The mural was showcased in the Hall of Negro Life, a section of the Texas Centennial Exhibition designed to celebrate Black culture and achievements.

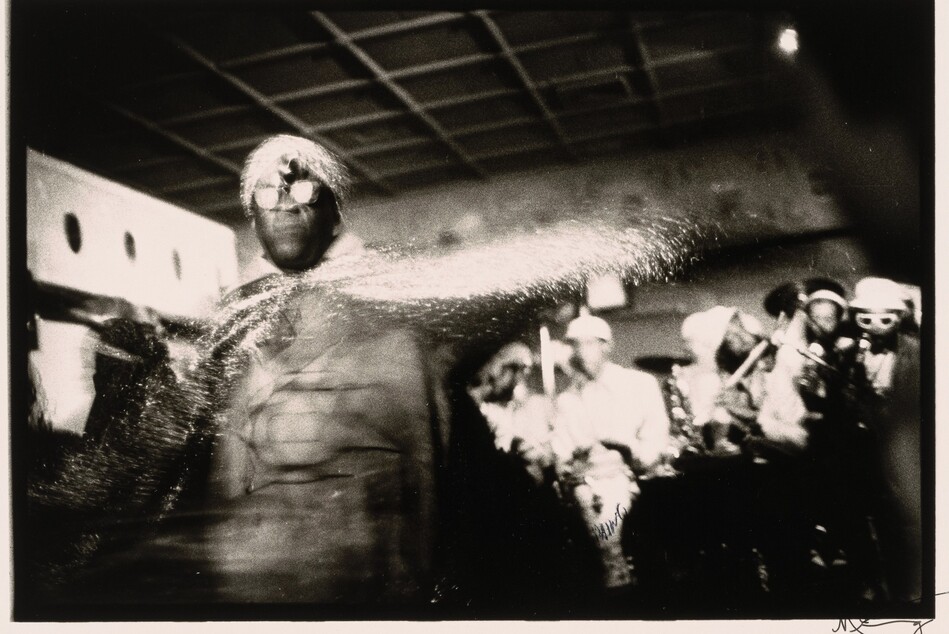

Hall of Negro Life, Texas Centennial Exposition, 1936

In the center of the painting, a man stands, his head and shoulders higher than all others. During the Harlem Renaissance, when Douglas lived and worked, many Black artists and writers looked to African cultures for artistic inspiration. The man’s facial features in profile resemble Dan masks from Liberia, with a narrow horizontal opening for his eyes.

He looks toward a star—likely the North Star, an important symbol of Black liberation. Decades before the Civil War, African Americans escaping Southern plantations on the Underground Railroad used the North Star as their guiding beacon, and after escaping slavery in Maryland (my own home state), abolitionist Frederick Douglass named his antislavery newspaper the North Star. In Into Bondage, a yellow beam of light streams from the North Star, becoming purple where it casts across the man’s face. This star represents hope—a way forward through oppression and anguish. Even as our protagonist is led into slavery, he still has mental agency. His mind is focused on freedom.

During this incredibly challenging moment in history—I look to the light. Often, the light is hard to find; every few days we witness a new story of unjustified violence against Black and brown people. As Will Smith said, “Racism is not getting worse—it’s getting filmed.” But in recent years, it seems more people are opening their eyes to the reality of anti-Blackness and other forms of discrimination than ever before. Communities came together in new and innovative ways to support each other through the dual pandemics of COVID-19 and systemic racism—even as we tried our best to remain six feet apart. It is in these acts of human kindness and connection that I see hints of light—our way forward, to freedom beyond the sickness of racism.

Originally published June 2020.

You may also like

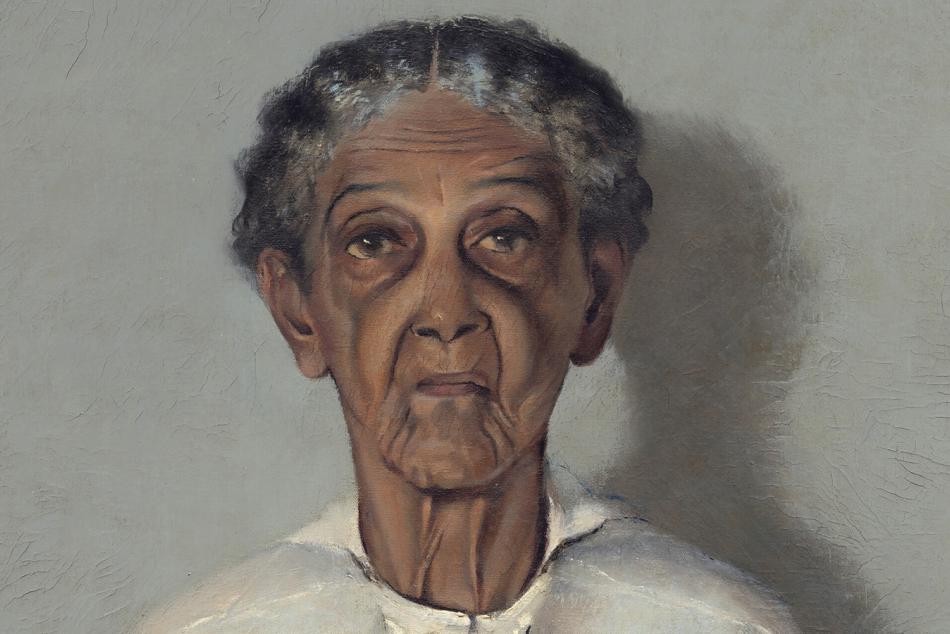

Article: Portrait by a Grandson: Motley’s Portrait of My Grandmother

Archibald John Motley Jr. captured the significance and dignity of his grandmother’s lived experience, ensuring that her story would be remembered.

Article: What Is the Black Arts Movement? Seven Things to Know

Learn how the "cultural revolution in art and ideas" celebrated Black history, identity, and beauty.