William Shakespeare’s Plays in Art

Some of the characters and plots in William Shakespeare’s works come directly from ancient and modern sources. Our Library exhibition Will’s World—European Literature in Shakespeare’s time explores the classic and modern writing that inspired the English playwright.

And in the 400 years since his first folio was published, Shakespeare’s plays have in turn inspired not only actors but also artists. Explore a range of artists’ interpretations of his most popular plays. Click the link to related scenes to read text from the Folger Shakespeare Library.

Two Gentlemen of Verona

As a teenager American artist Edwin Austin Abbey used a pen name from Shakespeare’s Hamlet. As a young adult, he illustrated hundreds of Shakespeare scenes magazines. “Who Is Sylvia? What Is She, That All the Swains Commend Her?” is one of seven large paintings of Shakespeare scenes that Abbey made in 1890.

The title echoes a song in act 4, scene 2 of The Two Gentleman in Verona. Proteus, one of the play’s main characters, sings the poem about his love Sylvia. Unfortunately for Proteus, “all the swains” (or suitors) are in love with Sylvia—including his friend Valentine. In Abbey’s painting, Sylvia lifts the skirts of her Italian Renaissance–style gown as she walks through a room of men enchanted by her presence.

King Lear

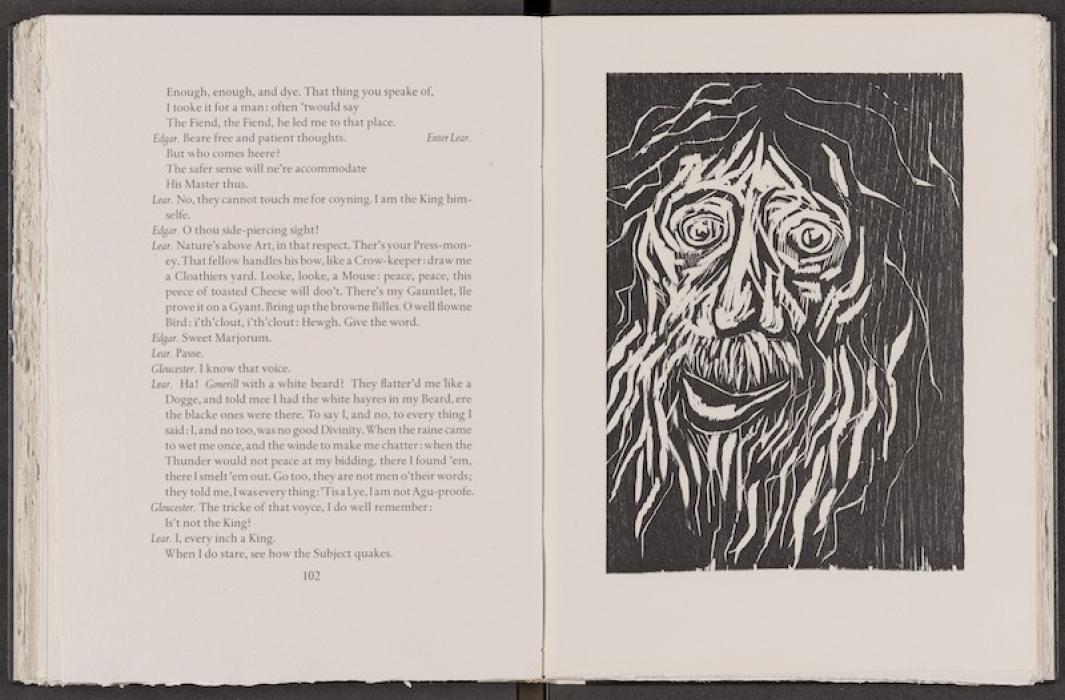

Canadian American painter, illustrator, printmaker, and typographer Claire Van Vliet paired her dramatic woodcuts with key characters and scenes from King Lear. She focused on faces and expressions, bringing out the emotions and drama of the text.

Van Vliet’s woodcuts show Lear gradually descending into madness. By act 4, scene 6, he has wild hair, a ragged beard, and a mystified look on his face. In the scene, a wandering Lear comes upon his son Edgar and his loyal nobleman Gloucester. The two don’t recognize him, but they do recognize his voice. When Gloucester asks whether this is the king, Lear replies, “Ay, every inch a king. / When I do stare, see how the subject quakes.” His mad expression in Van Vliet’s woodcut captures the full meaning of that line.

Romeo and Juliet

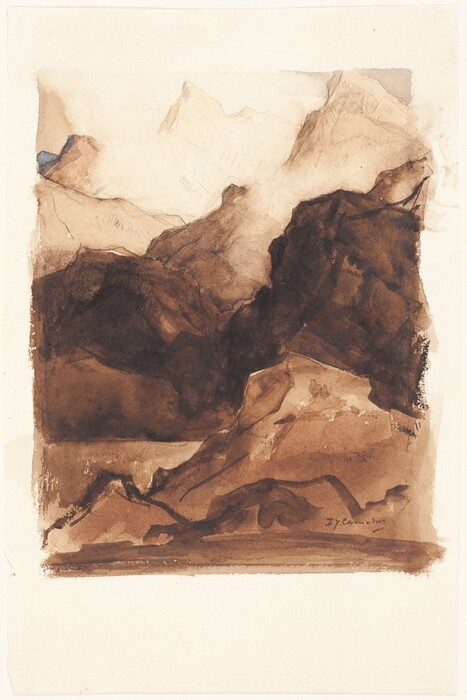

At first glance, Scottish artist David Young Cameron’s watercolor looks like an abstracted rocky landscape. But Cameron wrote these words on the back of the paper: “Night’s candles are burnt out, and jocund day / stands tiptoe on the misty mountain tops.”

The line comes from the beginning of act 3, scene 5 of Romeo and Juliet. Juliet pleads with Romeo not to leave, assuring him that they have more time before sunrise. But Romeo is fearful that they will be discovered, saying in the next line, “I must be gone and live, or stay and die.” The two never see each other alive again.

Macbeth

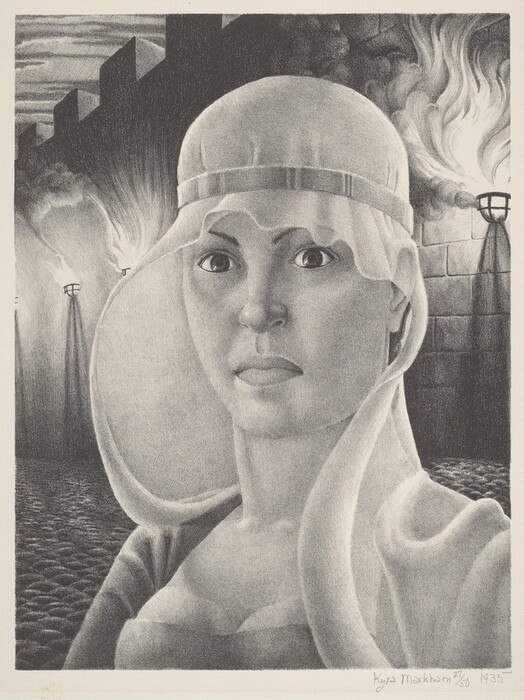

As a young woman, Kyra Markham acted professionally in American theaters and movies. In her 30s, she shifted her focus to art. She became known for her prints and lithographs and worked for the Federal Arts Project.

Her acting experience gives Markham a unique perspective on interpreting Shakespeare. In this print, she shows herself as Lady Macbeth. Her gaze is piercing, and behind her, billowing flames light up a castle wall. Does the composition show Lady Macbeth’s strength? Or does it come from the part of the play in which her guilt has driven her to sleepwalking?

Other interpretations of Macbeth:

- Wilhelm Lehmbruck, Macbeth V (The Vision of Lady Macbeth)

- Benton Murdoch Spruance, Macbeth - Ave 5

Hamlet

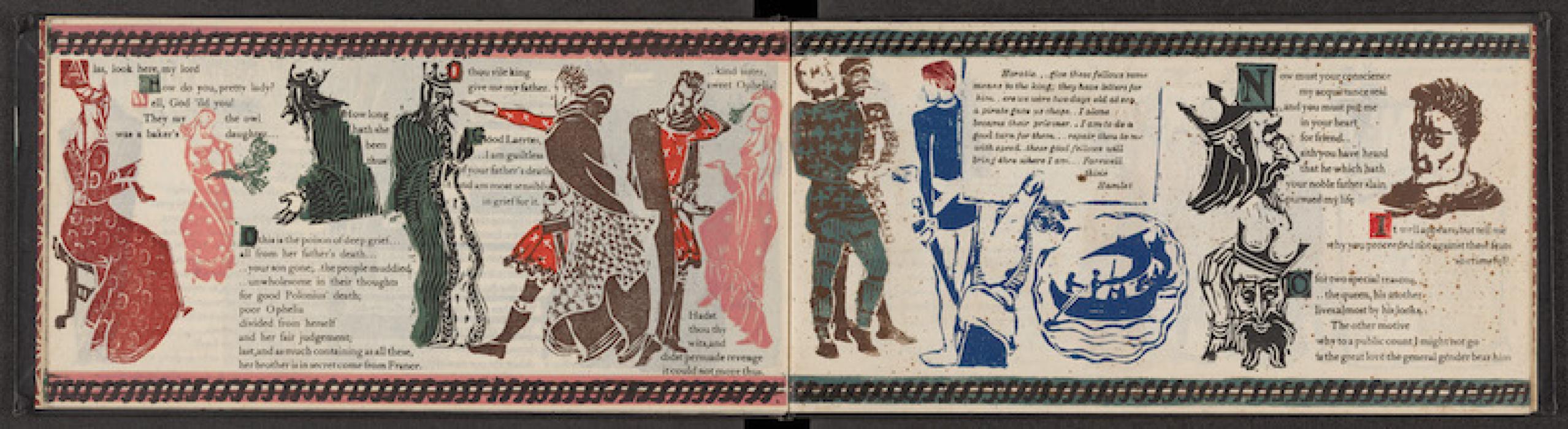

American artist and printmaker Dorothy Newkirk Stewart made this mesmerizing woodcut book of an abridged Hamlet in 1949. Stewart wove her colorful prints with the text, creating a book that almost reads like a contemporary graphic novel.

This page starts with act 4, scene 5. King Claudius enters to find Ophelia singing. He grows worried that she has had a mental break after the death of her father and son. Moving right, Stewart shows a scene in which Horatio reads a letter from his friend Hamlet. The artist simply shows a letter held in a hand. Below the letter and encircled in a bubble, an image tells the letter’s story of Hamlet being taken captive on a pirate ship.

Other interpretations of Hamlet:

- Eugène Delacroix, Hamlet and Ophelia (Act III, Scene I)

- Honoré Daumier, Hamlet

- Edouard Manet, The Tragic Actor (Rouvière as Hamlet)

A Midsummer’s Night Dream

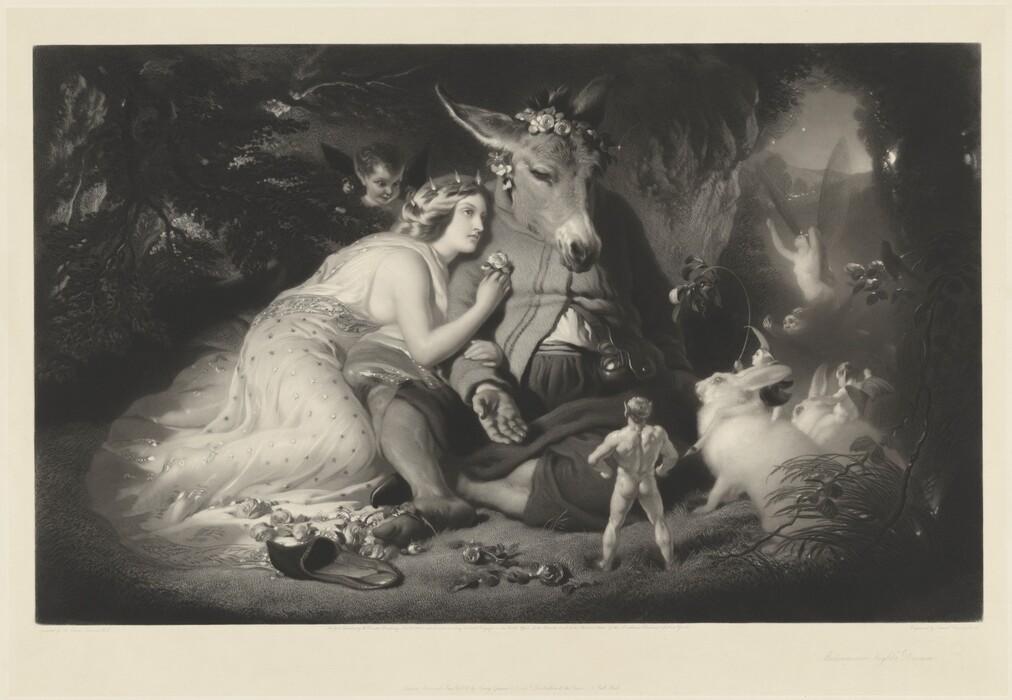

This print of a scene in A Midsummer Night’s Dream is based on a painting by Sir Edwin Landseer. Landseer was best known for painting animals, and he picked the perfect play to display those skills. The fairy queen Titania is under the spell of a potion (from the flower she holds in her hand) that made her fall in love with the first creature she saw—Nick Bottom, a man with the head of an ass. Landseer painted the ass’s head with precise detail and accuracy.

The scene comes from act 3, scene 1. The pair is in the woods, Titania resting her head on Bottom’s shoulder. They are surrounded by faeries and animals. Titania asks the fairies Peaseblossom, Cobweb, Mote, and Mustardseed to care for her new love.

The painting was exhibited and widely admired at London’s Royal Academy in 1851. Even Queen Victoria called the work “a gem, beautiful, fairy-like and graceful.” Lewis Carroll also enjoyed the painting when he saw it in 1857, noting in his diary that Bottom’s head and the white rabbit were “wonderful points.”

Other interpretations of A Midsummer Night’s Dream:

- Francis B. Shields, Midsummer Night Dream

- Harriet Goodhue Hosmer, Puck

Twelfth Night

In Twelfth Night, Viola is rescued from a shipwreck. She disguises herself as a young man, Cesario, and becomes a page (servant) for the Duke of Orsino. In act 2, scene 4, the duke is lovesick for a woman that doesn’t love him back. Cesario tries to give the duke hope that his beloved might just have difficulty expressing her feelings. Cesario (actually Viola) tells a story about his sister (actually herself) who died of lovesickness (actually alive—and in love with the duke). The title of Henry Peach Robinson’s photograph She Never Told Her Love comes from that story.

In Robinson’s photograph, his model acts as a young woman dying of consumption, presumably with a broken heart. His work recalls Cesario/Viola’s description of the sister: “She never told her love, / But let concealment, like a worm i' th’ bud, / Feed on her damask cheek. She pined in thought, / And with a green and yellow melancholy / She sat like Patience on a monument, / Smiling at grief.” Viola’s story isn’t true, though—she is talking about herself and her love for the duke.

Other interpretations of Twelfth Night:

- Sol Wilson, The Twelfth Night

You may also like

Article: Going through Hell? See Dante’s “The Divine Comedy” in Art

Travel with artists through Dante’s Nine Circles of Hell.

Article: Poems about Art

Explore works in our collection with celebrated American poets.