Robert Longo’s Huge Drawings of America’s Seats of Power

Did you think that was a photograph of the White House? American artist Robert Longo wants his drawings to surprise us. He likes to catch people off guard.

Longo has spent most of his career creating such drawings. Monumental, assertive drawings that make us reconsider what we are seeing.

The drawings are based on existing images that Longo combines and alters. Using different shades of black charcoal, he carefully translates and enlarges the pictures onto sheets of paper mounted on aluminum panels. Longo was part of a group of artist called the “Pictures Generation,” which shared this interest in studying and modifying photographs. Along with Cindy Sherman, John Baldessari, and Barbara Kruger, Longo grew up in a new world bombarded by mass media. Working in the 1970s and ‘80s, these American artists explored how images shape our understanding of the world and of ourselves.

Robert Longo’s Technique

Longo’s drawings can feel like stills from a black-and-white movie. In fact, he does have a director’s eye. The artist has made music videos for R.E.M. and New Order. He even directed the sci-fi film Johnny Mnemonic starring Keanu Reeves in 1995. Longo’s drawings reflect his experience as a filmmaker. They have a cinematic scale, and the stark, black-and-white contrast creates a sense of drama.

But if he’s a director, he’s also a sculptor. Studying sculpture in college has influenced his drawing technique in an unexpected way. In an interview, Longo said “I always feel like I’m carving the image out rather than painting the image. I’m carving it out with erasers and tools like that.” Instead of adding white to create highlights, he will often apply layers of black charcoal and then carefully remove it to reveal the white paper underneath.

As with any drawing, the type of paper is important. Longo prefers a particular paper: it has minimal texture, but the charcoal pigment sticks to it enough for him to create a layered effect. The paper’s manufacturer had planned to stop producing it, but now makes it in huge rolls just for Longo.

Challenging Our Idea of a Drawing

We often think of drawing as one of the most direct expressions of an artist’s personal style—like a signature or handwriting. But Longo doesn’t do this work alone. He works with assistants just like the titans of art history. Michelangelo, Rubens, and Rembrandt all had busy workshops to help create their paintings.

This practice is common, especially for artists who work at large scale and whose work is in high demand. But for Longo, involving multiple “hands” in creating his drawings adds a meaningful element. It is one of the ways he explores how images are constructed.

Maybe most of all, Longo challenges our expectations of the size of a drawing. His drawings wouldn’t fit in a notebook. They fill entire walls . . . of a very large room. They may be bigger than any drawings we’ve seen before. The three drawings in Longo’s Engine of State series, recently acquired by the National Gallery, are between 12 and 40 feet wide. That’s about the length of a school bus.

Longo creates these massive drawings using the lightest of materials—dust. These pictures made from powder depict buildings heavy with responsibility.

Robert Longo’s Engines of State

The presence of these enormous drawings matches the power within each building they depict. These structures house the three branches of the United States government: the Capitol (legislative); the White House (executive); and the Supreme Court (judicial). Surrounded by dark skies in Longo’s drawings, the landmarks feel ominous.

Standing in front of The Forest (White House) we look up at the iconic facade from below ground level. A ridge of dirt hides the bottom of the White House. Are we standing in a hole? A crater? Has something happened? Bare trees fill the left and right panels. Clouds hover above.

As we move to The Whale (The United States Capitol), we’re on the National Mall, not far from the National Gallery. We see the entire Capitol building—from the left wing housing the Senate chamber (the flag indicates that members are in session) to the right wing housing the House of Representatives (the empty flagstaff suggests that the House has adjourned). Against the dark sky, the building is starkly white—except for the dark shadows from the columns and passageways. Blurred marks of charcoal suggest the traces of the many people who have climbed these stairs.

Notably, one important feature of the Capitol is obscured: the Statue of Freedom on top of the dome. We can barely see it against the dark sky.

In The Rock (The Supreme Court of the United States—Split), the normally shining white marble exterior is a muddied grey. Longo has exaggerated the dark veins of the marble, making the building look like an ancient Roman ruin. It is split (as noted in the title) neatly in two. The division runs right through the word “justice” inscribed above the columns. Does this split refer to a political divide in the chambers?

While we recognize these buildings, Longo’s depictions of them are different enough to feel unsettling. By changing a familiar image and challenging our expectations of drawings, Longo encourages us to look more closely. “The most effective work convinces the audience to spend time seeing what they are looking at. Artists make so that people can see.”

You may also like

Article: Smithsonian Scientists on How Artists Depicted Five Curious Creatures

Staff at the National Museum of Natural History helped us identify the animals and insects in our collection.

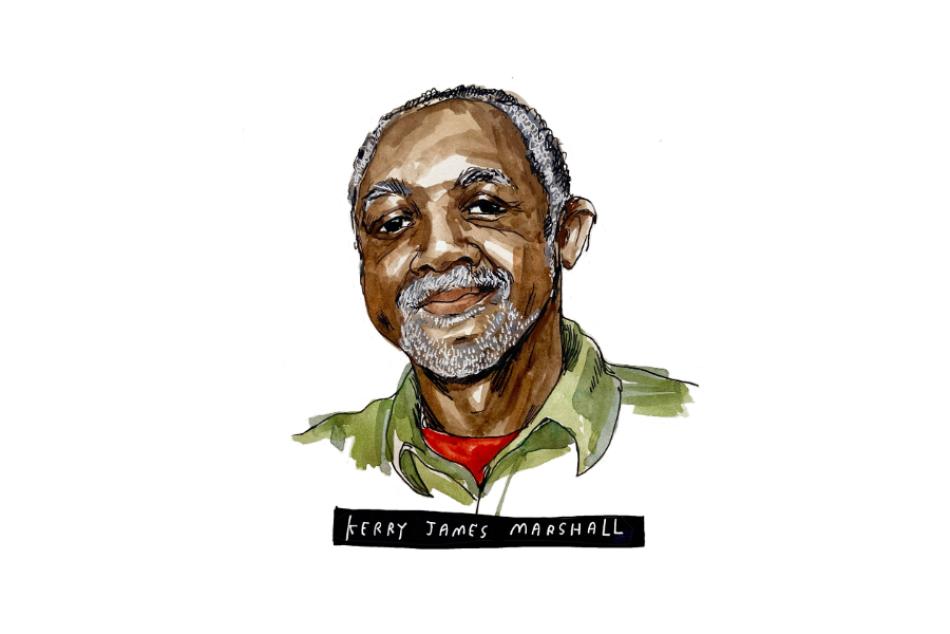

Article: Exquisite Corpse with Kerry James Marshall (and friends!)

The history painter takes inspiration from an old surrealist game — and so can we, as an opportunity for connection.