Miguel Luciano’s Portrait of a Puerto Rico in Crisis

Installation view of Miguel Luciano, Shields/Escudos, 2020, in no existe un mundo poshuracán: Puerto Rican Art in the Wake of Hurricane Maria (Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, November 23, 2022–April 23, 2023). Photograph by Ryan Lowry.

Shields/Escudos is a series of side-by-side metal shields strung together into what seems like an old yellow school bus. Through this work, first conceived in summer 2019, artist Miguel Luciano sums up the true cost of Puerto Rico’s economic and political crisis.

“This was actually made in Puerto Rico,” says Luciano, who usually creates in his Brooklyn-based studio. “For me, it was a conversion of all of these issues together that eventually led to this project materializing.”

Tracing Puerto Rican Labor and Land

Born in Puerto Rico and raised there and in the continental United States, Luciano has experienced the issues that plague the archipelago (group of islands) firsthand. They range from political corruption to mass migration. His work has long focused on colonialism and related political activism, both in Puerto Rico and in other Latinx communities across the United States.

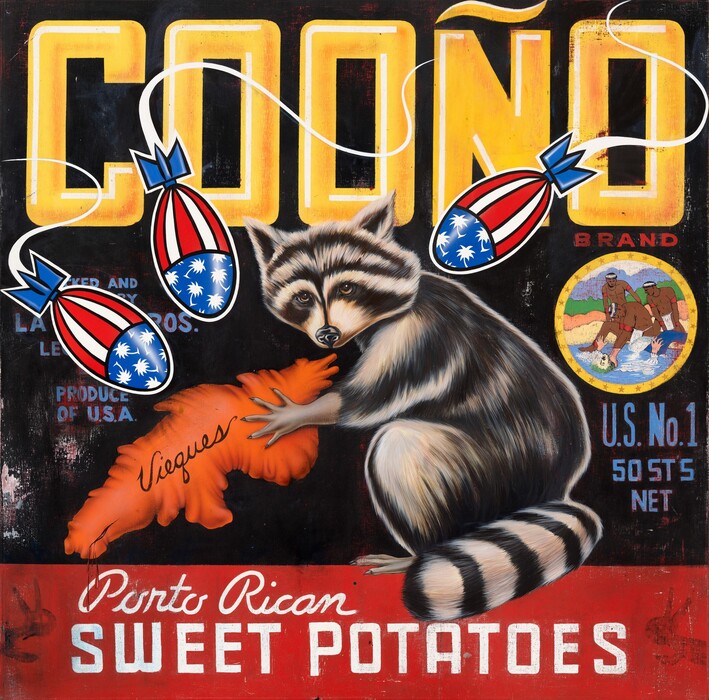

Take, for example, Louisiana Porto Ricans, now part of the National Gallery’s collection. This series is based on advertisements of Puerto Rican yams and sweet potatoes from the 1930s and ’40s. According to Luciano, those are some of the earliest depictions of Puerto Ricans in the United States. He recasts them as early 1900s ads to recruit Puerto Rican workers in Louisiana and Hawaii to sugar and pineapple plantations. “It becomes one of our early labor migrations,” Luciano says. “All of these paintings from that series have a lot of loaded critiques and embedded symbols that are strongly critical of the idea of [Puerto Rican] statehood.”

One such painting references the United States Armed Forces using the island municipality Vieques for military exercises in the late-20th century. Luciano depicts bombs printed with the American flag. They are falling around a racoon—an animal native to North America—who appears to steal a sweet potato in the shape of the island of Vieques. On the side, a little vignette reinterprets the famous legend of Diego Salcedo, a Spanish soldier killed by the Indigenous Taíno people in 1511. That is said to be a moment when the Taíno realized that the Spanish were not gods. In Luciano’s work, the drowning figure is an American instead of Salcedo. “It is about that story and a kind of transformation of consciousness. . . realizing that these are not our saviors,” the artist explains. The title appears at the top of the painting. It merges a racial slur for Black Americans that was used in the sweet potato advertising imagery with a Spanish expletive. Luciano combines them to convey outrage.

A Graveyard for School Buses and Abandoned Schools

Shields/Escudos, which was also recently added to the National Gallery’s collection, confronts us with Puerto Rico’s more recent history of economic crisis and activism.

Luciano started Shields/Escudos while visiting the archipelago in 2019. He stumbled on a graveyard of old school buses that had been out of commission since the administration of Governor Ricardo Rosselló enacted mass school closures in 2017.

“I started seeing a lot of abandoned schools,” he says. “[This junkyard] was kind of striking in addition to the schools.” Luciano recalls that every time he’d come back, more buses were in the junkyard, a direct impact from the school closures.

“They had lost their routes and they were not worth fixing, so I asked the owner to use some of the material,” Luciano explains. “I didn't know what the work was going to be, but I was drawn to the material as a symbol of a broken system.” When historic protests—that eventually led Rosselló to resign—began that summer, Luciano says, “all these things started to come together.”

Protest and Mourning Flags

The artist then made Shields/Escudos a work with multiple meanings. On one side, we see the classic yellow shade and lettering of the school buses. On the other, Luciano painted black-and-white Puerto Rican flags.

Over the past decade, as Puerto Rico’s debt crisis has deepened, the black and white has come to symbolize collective mourning. One significant example is a famous door in Old San Juan, a historic district in the capital. Decorated with Puerto Rico’s red, white, and blue flag, the door had become a hot spot for tourists taking pictures. But in 2016, after the Puerto Rico Oversight, Management, and Economic Stability Act (PROMESA) established an oversight board to manage Puerto Rico’s finances, the door’s creators painted it black and white.

Luciano has been including black-and-white Puerto Rican flags in his work around 2017. In Shields/Escudos, the symbol is a nod to the protests students and activist groups held in response to the oversight board enacting public spending cuts. The protesters have often had to shield themselves from police.

Shields/Escudos comes to the National Gallery following a stint in a recent exhibition at the Whitney Museum of American Art: no existe un mundo poshuracán: Puerto Rican Art in the Wake of Hurricane Maria, the largest survey of Puerto Rican art in the United States. Chief curatorial and conservation officer E. Carmen Ramos has known Luciano since he moved to New York in the early 2000s. She first saw Shields/Escudoss during a visit to Luciano’s studio ahead of the Whitney exhibition.

“At the time the National Gallery was acquiring The Flag is Bleeding by African American artist Faith Ringgold. She created this masterpiece during the violence and unrest of the 1960s civil rights. I see a resonance between Ringgold and Luciano. Luciano uses a flag—in this case the Puerto Rican flag—to register protest, but in our current moment,” says Ramos. “Luciano does this in his own way, shaped by the resonance of the specific materials he seeks out and transforms.”

She had long been familiar with Luciano's Cooño. “I see it in dialogue with a long history of works by artists of color who boldly challenge racist advertising imagery. I think of Robert Colescott, Betye Saar, Rupert García—to name a few.”

“Having two works in our collection that address pivotal moments in Puerto Rican history, and by one of the leading Puerto Rican artists, is just extraordinary,” Ramos adds.

Luciano’s career has confronted viewers with the realities of the Puerto Rican experience for decades. He is aware that Louisiana Porto Ricans and Shields/Escudos hold a deeper meaning inside the halls of the National Gallery. “I’m thrilled that this work is going there because it creates an opportunity for a difficult conversation in the nation’s capital at a time when I think it’s important to have these complicated conversations,” the artist says.

Top image: Installation view of no existe un mundo poshuracán: Puerto Rican Art in the Wake of Hurricane Maria (Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, November 23, 2022–April 23, 2023). From front to back: Miguel Luciano, Shields/Escudos, 2020; Gabriela Salazar, Reclamation (and Place, Puerto Rico), 2022. Photograph by Ryan Lowry.

You may also like

Article: 9 Latinx Artists You May Not Have Heard Of

Learn about the lives and works of artists of Latin American descent working in the United States from the 1930s to today.

Article: The Collective Memory of Amalia Mesa-Bains

Through her evocative installations, the pioneering Chicana artist seeks to connect the past with the present.