How Mark Rothko Made Paintings on Paper

Mark Rothko made more than 1,000 paintings on paper in his life. He considered these some of his very best work, including them in important exhibitions, selling them to collectors, and giving them as gifts.

But at the time of Rothko’s death in 1970, some paintings on paper remained in his studio, not yet prepared for display. These works “in process” are full of valuable information about the artist’s practice and preferences.

Ahead of our exhibition, Mark Rothko: Paintings on Paper, our curators and conservators examined some of these works for clues about Rothko’s methods and materials. Read on for an inside look at the artist’s tools, his brushwork and layering, his treatment of edges, and his experiments with framing and mounting.

Boards and Easels

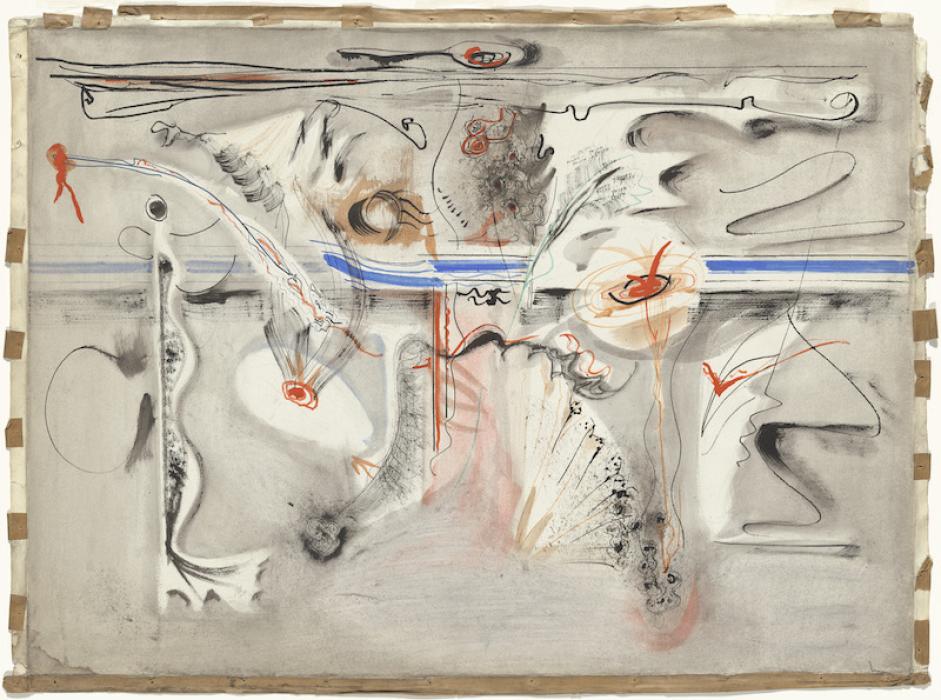

A watercolor from the mid-1940s offers a glimpse into Rothko’s process at that time. He painted on a wet sheet of good quality Whatman watercolor paper that was taped on all four sides to an upright board. Rothko removed the finished watercolor from the board, cutting and tearing its edges. Some of the pressure-sensitive paper tape still remains, now brittle and ragged. If he had exhibited or sold the work, Rothko would have cleaned up the edges.

This painting appears in a rare photograph of Rothko at work in his home studio. Maybe he is about to apply the final touches—only the bold red highlights are missing

By the late 1960s, Rothko was making his paintings on paper using two plywood “easels.” They were giant: roughly 15 feet tall by 11 feet wide. In fact, Rothko had previously used one of the easels to paint his large canvases. A pulley system affixed to the easel allowed him to raise and lower the canvases.

National Gallery conservators have reassembled and restored that easel for Mark Rothko: Paintings on Paper. The colorful paint we can see is the result of Rothko’s working process. As he painted on sheets taped to the easel, he brushed beyond their edges. This left rectangular silhouettes of finished paintings.

Frames and Mounts

Decisions about how to display a painting were an important part of Rothko’s process. He cared deeply about offering viewers an opportunity to engage with his work directly and without interruption. “A painting is not a picture of an experience; it is an experience,” he said.

When exhibiting his 1940s watercolors, Rothko preferred minimal frames with slim profiles and no mats. Sometimes he even avoided frames altogether, mounting the paintings on boards or other supports. For example, the edges of this watercolor from 1944/1945 reveal that it was folded around and tacked to a support, most likely a wooden stretcher.

Mark Rothko, Untitled, 1944/1945, watercolor, ink, and graphite on watercolor paper, sheet: 57.94 × 79.06 cm (22 13/16 × 31 1/8 in.), Gift of The Mark Rothko Foundation, Inc, 1986.43.217. Copyright © 2023 Kate Rothko Prizel and Christopher Rothko

By 1949, Rothko had settled on the “classic format” we recognize best today: soft-edged rectangles arranged vertically against a single-color background. When he painted these works on paper, he insisted that they be displayed without frames or glass. Instead, he mounted them to a support of linen or board and then to stretchers or strainers.

But some of Rothko’s “classic format” paintings on paper have remained as loose sheets. To honor the artist’s intentions, National Gallery conservators carefully mounted several works for display in Mark Rothko: Paintings on Paper.

Conservators Minah Song and Kim Schenck preparing to mount one of Rothko’s paintings onto an aluminum panel. Photo by Munyang Tengen, Howard University undergraduate intern.

Borders and Edges

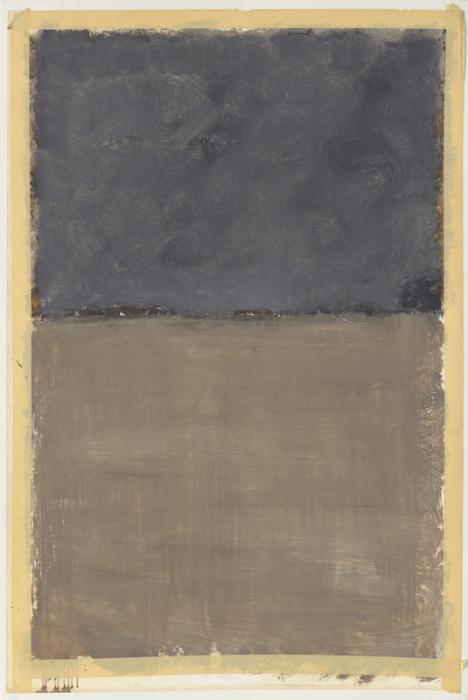

Rothko never stopped experimenting with his abstract compositions. Each painting was an invitation to test new possibilities. We can see traces of his decision-making in an early work from the Brown and Gray series, possibly the first. Rothko painted a taupe lower field in broad, grid-like strokes. The upper field is charcoal-gray, with loose, brushy boundaries.

After finishing the fields, Rothko covered their outer edges with masking tape, which he never removed. Through this simple experiment, he tested the effect of a hard-edged border. Rothko then used a similarly hard-edged border of exposed white paper for the rest of the Brown and Gray series, which marked an important development in his late work.

Mark Rothko, Untitled, 1969, acrylic on wove paper and pressure-sensitive tape, National Gallery of Art, Gift of The Mark Rothko Foundation, Inc., 1986.43.290. Copyright © 2023 Kate Rothko Prizel and Christopher Rothko

Brushwork and Layering

At Rothko’s death, many paintings on paper were still in his studio, not yet prepared for display or sale. Looking at one of those works—with the full edges of the sheet still intact—reveals how Rothko made it. He began by brushing acrylic paint in black and red washes onto a sheet that was stapled to one of the large easels. We can see staple holes in the edges, and drips and strokes over them. The artist then taped all four sides of the sheet, covering the staples and setting the boundaries of the final composition.

Next, Rothko applied layers of yellow, orange, and red. On top of this fiery base, he painted two black rectangular forms. He varied the tightness of his brushstrokes and the gloss of his paint. When the artist was finished, he peeled the tape away (though a few bits remain along the upper edge) and pulled out the staples.

Mark Rothko, Untitled, 1968, acrylic on wove paper, National Gallery of Art, Gift of The Mark Rothko Foundation, Inc., 1986.43.250. Copyright © 2023 Kate Rothko Prizel and Christopher Rothko

The drips, streaks, and traces of movement visible in paintings like this one reveal Rothko’s energetic practice. In return, he hoped for active engagement from viewers: “The artist invites the spectator to perform an aerial feat of flying from point to point, attracted by some irresistible magnet across space, entering into mysterious recesses.”

Banner image: Alexander Liberman, Mark Rothko mixing paint, ca. 1964, chromogenic process, Alexander Liberman photography archive, ca. 1925-ca. 1998, The Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles (2000.R.19), © J. Paul Getty Trust

You may also like

Article: Who Is Mark Rothko? 9 Things to Know

Brush up on key and unexpected details about the modern artist, best known for his colorful abstract paintings.

Article: Artists Who Inspired Mark Rothko

Learn about some of the artists the modern painter was in dialogue with throughout his career.