A History of the Dutch Painting Collection at the National Gallery of Art

Arthur K. Wheelock Jr.

The National Gallery of Art has one of the finest collections of Dutch art in the world, but its distinctive character reflects the attitudes of the Gallery’s founding fathers.[1] When the Gallery opened its doors to the public on March 17, 1941, it was largely through the generosity and foresight of Andrew W. Mellon (1855–1937). Mellon not only donated his European and American masterpieces to the nation but also provided funds for John Russell Pope’s grand, neoclassical marble building and for an endowment for the museum. The guidelines that Mellon established for his gift were that the gallery should be a public/private institution with free access for all. Federal funds would support upkeep and salaries but would not be used for the purchase of works of art. Acquisitions were to be restricted to works of outstanding quality, commensurate with those in Mellon’s own collection. Mellon was also insistent that the museum should be called the National Gallery of Art and not the Mellon Gallery, a decision that had important ramifications for its future.

David E. Finley (1890–1977) and John Walker (1906–1995), the Gallery’s first director and chief curator, were able to attract other major collectors who also felt that a National Gallery of Art, as envisioned by Andrew Mellon, would be an important cultural and scholarly institution for the “use and enjoyment of the people of the United States.”[2] Mellon’s gift of 123 paintings and 23 sculptures was hardly enough to fill the spacious new galleries, and a long-standing joke at the Gallery is that the guards’ main job on opening night was to direct visitors to the next painting. In fact, Mellon’s paintings and sculptures were not the only treasures on view that evening. They were supplemented, and even outnumbered, by Italian Renaissance paintings and sculptures donated by Samuel H. Kress (1863–1955). Kress and his brother, Rush (1877–1963), who would continue to acquire major works on behalf of the Gallery, later expanded the scope of their collection to include French, German, Flemish, and Dutch paintings.

In terms of Dutch art, the most important Gallery benefactor was Joseph Widener (1871–1943), who agreed to donate the remarkable collection of European paintings, drawings, and decorative arts that his father, Peter A. B. Widener (1834–1915), had assembled at Lynnewood Hall, the Widener estate near Philadelphia. In 1942, one year after the National Gallery of Art officially opened, Widener donated his collection, which came to Washington the following year. In 1943, Chester Dale (1883–1962) followed suit and donated the Gallery's first Dutch still life and its first painting by Peter Paul Rubens (1577–1640). That same year another important donation came to the Gallery from Lessing J. Rosenwald (1891–1979), whose outstanding collection of prints and drawings included many works by Dutch artists, particularly Rembrandt.

Within the span of a just few years, this young institution became an incredible storehouse for treasures of European and American art, worthy of its aspirations to be the nation’s premier art museum. It was, however, essentially a collection of collections. While each of these was among the most important of the time, in reality they had vastly different characters. Unlike Mellon’s relatively small ensemble of works of very high quality, Kress’s collection was extremely large, yet its remarkable overview of Italian art included works that were not always of the level of quality and condition to which Mellon had aspired. Consequently, over the years many adjustments were made to refine the collection.[3] P. A. B.Widener, in a similar fashion, had amassed an enormous collection—consisting of over 400 paintings—but through a combination of judicious pruning and important acquisitions during the 1910s and 1920s, the number of works was reduced and the quality rose. In 1942, when Joseph Widener donated the collection to the nation, it contained about 100 paintings, all of which were considered to be among the best available works of the artists represented.[4]

Time would demonstrate that masterpieces in the eyes of one generation of collectors were not always viewed positively by a later generation. The attribution of a number of Widener’s prized Rembrandts would come to be questioned, including the most famous work in his collection, The Mill (fig.1).[5] Even a few of Andrew Mellon’s acquisitions were not without critics, and some of his purported Vermeer paintings were later determined to be forgeries.[6] Nevertheless, on March 17, 1941, when the National Gallery of Art opened its doors, these issues had not yet surfaced or were of little concern. The twenty-six Dutch paintings from the Mellon collection were received with great public acclaim.

Andrew Mellon developed his interest in collecting old master paintings in the late 1910s, probably inspired by the example of his friend Henry Clay Frick. At that time Mellon had just purchased a new home in Pittsburgh, where he was a successful banker and entrepreneur.[7] After he was named Secretary of the Treasury in 1921, Mellon moved to Washington, where he bought a larger residence and needed more paintings to fill its walls. Two art dealers with whom he had already established a relationship in Pittsburgh, Charles Carstairs from M. Knoedler and Co. and Joseph Duveen, seized this opportunity to offer Mellon old master paintings suitable to his wealth and status.[8] Mellon, who quickly developed strong opinions about the types of paintings he wanted, primarily Dutch and British, and the prices he was willing to pay, became more knowledgeable and decisive about the direction of his collecting interests than is generally recognized.[9]

During the 1920s Andrew Mellon developed his idea about founding a National Gallery of Art, perhaps with the encouragement of Joseph Duveen.[10] With this plan in mind, Mellon made his most extraordinary art acquisitions while serving as Ambassador to Great Britain in the early 1930s. In a complex arrangement with the dealers M. Knoedler, P. & D. Colnaghi, and the Matthiesen Gallery, Mellon acquired, at very high prices, twenty-one masterpieces from the Hermitage in Saint Petersburg, Russia, among them paintings by Rembrandt and Frans Hals. These works were included among the Dutch paintings he donated as part of his gift to the nation, which comprised, in total, nine paintings by Rembrandt and five by Hals, as well as landscapes by Aelbert Cuyp and Meindert Hobbema, and genre scenes by Gerard ter Borch, Pieter de Hooch, Nicolaes Maes, Gabriel Metsu and Johannes Vermeer.

After the Widener collection was installed at the National Gallery of Art in 1943, the number of Dutch paintings exhibited more than doubled. Many of Mellon’s collecting interests had overlapped with those of the Wideners, which resulted in a disproportionate representation of certain artists. For example, combined, these two extraordinary collections contained no fewer than twenty-three Rembrandt paintings, more than a third of the total number of Dutch paintings Andrew Mellon and Joseph Widener donated to the Gallery. Among the other artists they both collected were Frans Hals (eight paintings), Meindert Hobbema (six paintings), Aelbert Cuyp (four paintings), and Johannes Vermeer (three paintings). Differences, however, also existed in their taste in Dutch art. P. A. B. Widener admired Jacob van Ruisdael’s landscapes and low-life genre scenes by artists such as Adriaen van Ostade, Isaac van Ostade, Paulus Potter, and Jan Steen, none of which appealed to Mellon. Neither the Mellon nor the Widener collection had a still life painting at the time of the gift. Only one Dutch still life was to be seen at the Gallery during the 1940s and 1950s, a painting by Willem Kalf that came in 1943 as part of the Chester Dale Collection.[11]

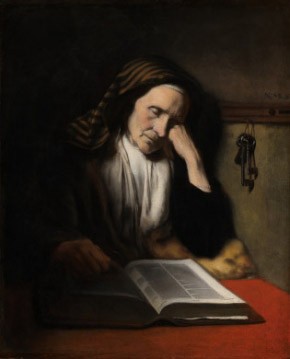

During the Gallery’s early years, its collection of Dutch paintings was essentially a period piece that reflected the tastes and aspirations of two American millionaire collectors from a narrow period of time—between 1894, when Widener purchased his first Rembrandt, Saskia van Uylenburgh (fig. 2) and 1936, when Mellon made his last acquisition of a Dutch painting, Nicolaes Maes’ An Old Woman Dozing over a Book (fig. 3). Unfortunately, little is known about the considerations that underlay the decisions they made when acquiring specific works of art. Widener and Mellon were not, of course, the only wealthy Americans collecting at that time, and, in general, the types of paintings they purchased were comparable to those that appealed to, among others, Benjamin Altman (1840–1913), Henry Clay Frick (1849–1919), Isabella Stewart Gardner (1840–1924) and J. P. Morgan (1837–1913).[12] Moreover, despite their wealth, one cannot assume that they acquired everything they desired since they were not always the first choice among dealers selling their major old master paintings.[13] Nevertheless, each of their collections has an internal consistency that reveals a point of view, even a collecting philosophy, albeit one that must have evolved over time as their own level of knowledge and aspirations for their collections increased.

The canon that Andrew Mellon and the Wideners followed was one with an English flavor, based largely on John Smith’s influential catalogue raisonné of Dutch and Flemish artists, and on the types of Dutch paintings they saw in the Wallace Collection and the National Gallery, London, where celebrated works by the recently rediscovered Frans Hals and Johannes Vermeer could also be found.[14] As far as P. A. B. Widener and Andrew Mellon were concerned, the Dutch Golden Age began in the 1630s and had ended by the late 1660s. If a painting from those decades came from an English collection, or was being sold by an English dealer, so much the better. Rembrandt held supreme, but the great overarching appeal of Dutch art for these collectors was its truthfulness to nature, particularly in regards to portraiture (Hals), landscape (Cuyp and Hobbema), and genre scenes (Vermeer, Ostade, Ter Borch). Dutch still lifes may have been of little interest, but neither were paintings by mannerists, Caravaggists, Italianates, fijnschilders, or classicists, none of which were included in the Widener and Mellon collections at the time they were given to the Gallery.

The Widener story is particularly important for understanding the character of the Dutch paintings at the National Gallery of Art. Despite his reputation as a wealthy “robber baron” who knew little about art when he began collecting, followed bad advice, and generally made a number of questionable decisions when building his collection, P. A. B. Widener’s engagement in his collecting activities was greater than is traditionally believed.[15] He learned from his early mistakes, and by the early 1900s he sought expert guidance to correct them.[16] Working with Cornelius Hofstede de Groot (1863–1930) and Willem Valentiner (1880–1958), P. A. B. and Joseph Widener de-accessioned weaker Dutch paintings and those they no longer deemed important or desirable, and they sold or traded a number of paintings to acquire better works of art.[17] As P. A. B. Widener became more concerned about the importance and quality of the works he was buying, he traveled widely, even as far as Russia, in search of masterpieces and to negotiate purchases.[18]

P. A. B. Widener came from humble origins, but he had grown in wealth and political clout through shrewd investments during and after the Civil War. Soon he built a large residence in Philadelphia and, as many of the newly rich of this era, he began to collect paintings, in large part Dutch. He had a sympathetic eye for low-life Dutch genre scenes, an interest that probably derived from his Germanic roots as well as from his modest beginnings. The quest for Dutch art also relates to a broader fascination in the Netherlands then current in late nineteenth-century America.

As Annette Stott has explained, the country was then in the midst of a “Holland Mania,” largely stemming from the writings of the historian John Lothrop Motley.[19] In the first of his influential books, The Rise of the Dutch Republic (1855), Motley wrote about the revolt of the Protestant Dutch against the evil Spanish Empire. He described how the brave, hard-working Dutch opposed dogmatism and persecution, courageously resisted foreign despotism, and expressed their love of liberty and desire for self-government. In his text Motley explicitly drew parallels between the Dutch Revolt and the American Revolution, as well as between the leader of both rebellions, the Prince of Orange (William the Silent) and George Washington.[20] In A History of the United Netherlands (1867) Motley emphasized how Dutch policies of tolerance, equality, and freedom were models for Americans to follow in their quest to become a world power.

By the early 1890s, when Widener was beginning to collect old master paintings, such sentiments were widely accepted, with some authors asserting that the Dutch system of government had provided precedents for institutions and political concepts fundamental to the United States. [21] The arguments that the Netherlands and the United States shared moral and ethical values came at a time when America was celebrating its heritage and its legacy at the Centennial Celebration in Philadelphia in 1876, and at the World’s Columbian Exhibition in Chicago in 1893. The World’s Fair, in particular, set the stage as the dawn of a new era, and commemorated man’s great achievements and aspirations, particularly in art and architecture.

The year after the World’s Fair, 1894, was a seminal one for Widener. He significantly raised the level of his collecting aspirations and began to buy important Dutch paintings.[22] Widener’s new approach is evident in the quality of the dealers in London and Paris with whom he worked, including P. & D. Colnaghi, Thomas Agnew, and Charles Sedelmeyer. Among the masterpieces he bought in that year were no fewer than five Dutch paintings that later became part of the Widener gift: Rembrandt’s Saskia van Uylenburgh (see fig. 2), Aelbert Cuyp’s Lady and Gentleman on Horseback (fig. 4), Meindert Hobbema’s The Travelers (fig. 5), Pieter de Hooch’s The Bedroom (fig. 6), and Jacob van Ruisdael’sForest Scene (fig. 7).[23]

Each of these acquisitions of Dutch art helps define Widener’s collecting ideals at this crucial moment. Beyond being a beautiful image and a portrait of the artist’s wife, Saskia was significant in that it was by Rembrandt, and acquiring a Rembrandt defined one as a major collector. Pieter de Hooch’s depictions of carefully maintained interiors expressed a positive view of domestic life that would have appealed to Widener with his middle-class Protestant background. Aelbert Cuyp was admired by the English for his atmospheric light effects, but this particular painting also came from the distinguished collection of Adriaen Hope. Meindert Hobbema was celebrated for his truthfulness to nature, and Jacob van Ruisdael was one of the heroes of the nineteenth–century romantics because of the poetic grandeur of his landscapes.

What raised Widener’s sights to such a level is not certain, but I believe his new approach reflects the influence of the German art historian, Willem von Bode (1845–1929), director of the Kaiser-Friedrich-Museum in Berlin, who had come to America in 1893 to visit the World’s Fair. After the Fair, Bode visited art collectors and museums along the Eastern seaboard, going as far south as Philadelphia. Bode does not identify the collectors he met there, but he certainly would have spoken to John G. Johnson, William Elkins, and Widener, three wealthy Philadelphians who were beginning to acquire old master paintings. He had close contacts with all the dealers from whom Widener acquired his paintings in that year, and probably directed Widener to them.[24]

Bode was, beyond all else, a Rembrandt expert, and his impact on the collecting of Rembrandt paintings in America cannot be overestimated.[25] In the nineteenth century, Rembrandt’s fame had risen to extraordinary heights, in part because his life story—his origins as a miller’s son, his marriage to Saskia and her untimely death, his fame and subsequent bankruptcy, as well as the sense that he spent his later years as an isolated genius—appealed to those who lived during the romantic era. Rembrandt’s expressive manner of painting appealed to artists like J. M. W. Turner, who wrote movingly about the Dutch master’s use of light and dark in The Mill (fig. 1).[26]

Bode, who also had a romantic view of Rembrandt, admired the Dutch master’s broad brushwork and chiaroscuro effects, and introduced a number of unfinished oil sketches into Rembrandt’s oeuvre. For Bode, the way in which Rembrandt suppressed surface details allowed him to render “souls rather than . . . existences.” While he noted that not all of Rembrandt’s works were of equal quality, he attributed their failings to be “merely the defects incidental to his great and original genius.”[27] Bode’s appreciation of Rembrandt’s late style was shared by P. A. B. Widener’s advisor, Hofstede de Groot (who had assisted Bode in writing his corpus of Rembrandt’s paintings), and his curator, Valentiner (who had been Bode’s protégé and Hofstede de Groot’s assistant), which helps explain the large number of late Rembrandt paintings, including oil sketches, that P. A. B. and Joseph Widener acquired.

It is, thus, not surprising that many of the Widener paintings are connected to Rembrandt’s biography. Widener acquired Saskia from Sedelmeyer, the very dealer that would publish Bode’s corpus of Rembrandt’s paintings a few years later. He would have to wait until 1908 to purchase from Agnew the famous Self-Portrait from the Rothschild collection (fig. 8). In 1911 Widener made his most important Rembrandt acquisition,The Mill (see fig. 1). Not only was The Mill thought to represent Rembrandt’s father’s mill, but its dark, brooding character was seen to express Rembrandt’s “financial worries, social stress, and personal bereavements” at the time of his bankruptcy. When Widener acquired the painting, he sent it to Berlin to be examined by Bode and to be cleaned by Bode’s restorer, Professor Hauser.[28] Two years later, when visiting Widener, Bode described this work as “the greatest picture in the world.”[29]

Americans’ ability to acquire old master paintings was abetted by changes in tax laws, both in England and in the United States. In 1894 the English government introduced death duties, which meant that many aristocratic families were forced to sell their art treasures. Equally important for P. A. B. Widener, and for other wealthy American collectors, was the fact that in 1909 the United States government dropped import duties for art entering the country. For Widener, the timing could not have been better: he was then actively working to improve the quality of his collection. He took advantage of the new tax laws to make a series of significant acquisitions, not only The Mill, but also Vermeer’s Woman Holding a Balance (fig. 9), both of which he purchased in 1911.[30]

The heritage of the Widener/Mellon taste was still very much in evidence when I came to Washington as a David E. Finley Fellow in 1973 and it remained so for many years thereafter. I remember vividly my first walk through the oak-paneled Dutch galleries. They were big, imposing, and austere, and spaciously hung with masterpiece after masterpiece. The Gallery’s twenty-three dark and brooding Rembrandts were exhibited in two non-contiguous galleries, one with works from Mellon and the other with the Widener Rembrandts. The division was intentional, and instituted as part of the negotiations that had persuaded Joseph Widener to donate the collection to the Gallery. The galleries were lit primarily by skylights, which did little to penetrate the thick coats of discolored varnish that covered the paintings, all of which were framed in ornate, gilded frames. The tenor was somber and hushed, appropriate for the importance of the artists represented, and even the glow of Aelbert Cuyp’s light-filled landscapes in adjacent rooms did little to lighten the mood.

John Walker, the Gallery’s director from 1955 to 1970, had always felt that the light levels should remain low, and they were. Walker also liked the patina of discolored varnish. Hence, by late afternoon the paintings were particularly difficult to view. Walker’s primary art historical interest was with Italian art, so, as a result, he had paid little attention to the Dutch collection. Only twelve additional Dutch paintings had been added since 1943, eight as a result of gifts and bequests, and four by purchase. Although these works had somewhat expanded the range of artists and types of paintings represented, particularly two important paintings by Pieter Saenredam that Kress had donated in 1961, and Joachim Wtewael’s Moses Striking the Rock (fig. 10), purchased in 1972, the predominant Mellon and Widener taste, and the exceedingly unbalanced presentation of Dutch art it presented, had changed but little.[31]

In 1973, curatorial research at the National Gallery of Art was still in its infancy. Specialized curators had yet to be appointed, and curatorial records on individual paintings were sparse. Elsewhere, radical new assessments of Dutch art were taking place. For example, Horst Gerson, in his 1969 publication of Abraham Bredius’ corpus of Rembrandt paintings, had questioned the attribution of a number of the Gallery’s prized Rembrandts, including the 1650 Self-Portrait that P. A. B. Widener had so proudly acquired in 1908 (see fig. 8).[32] Gerson’s critical assessments cast a pall over the entire collection, but his conclusions were rejected within the Gallery. In 1969, Egbert Haverkamp-Begemann, who was then the visiting Kress Professor, helped organize an in-house exhibition to celebrate the 400th anniversary of Rembrandt’s death, but he was not given free reign to express his own doubts.[33] The Gallery had remained in a time warp, little interested in re–examining the attributions of the works on its walls.

A change in approach, however, occurred when J. Carter Brown (1934–2002) became director in 1970. Together with his deputy director, Charles Parkhurst (1913–2008), Carter Brown established a conservation department. When I arrived in 1973, none of the Dutch paintings had undergone treatment, yet at least there was interest in discovering more about the works hanging on the walls. One of my most vivid memories of that year remains the experience of examining the Rembrandt paintings with Arie Bob de Vries (1905–1983), the former director of the Mauritshuis, who was then the visiting Kress Professor. Together with Kay Silberfeld, one of the Gallery’s conservators, we closed the Rembrandt rooms day after day, brought in stepladders, strong lights, ultraviolet lights, and magnifying glasses to learn more about the paint layers and old restorations that lay beneath the discolored varnish that covered all these works.

These sessions evolved into a “Rembrandt project,” which I undertook as a part-time “research curator” after my fellowship had ended in April 1974. That project allowed me to research the Gallery’s Rembrandts and build up the curatorial files. It also involved travel to examine Rembrandt paintings in other collections. Shortly after I was appointed Curator of Dutch and Flemish paintings in the fall of 1975, Kay Silberfeld began her conservation treatment of one of the Gallery’s Rembrandts: Saskia (see fig. 2). Not surprisingly, given the large size of the collection, not all of the Rembrandt paintings turned out to be entirely by the master’s own hand. Several had been created in Rembrandt’s workshop, often with the master’s participation. By the time that the catalog of the Dutch collection was published in 1995, a number of attributions of Rembrandt paintings had been revised as, for example, the Widener “Self-Portrait,” which is now designated Portrait of Rembrandt (see fig. 8).[34] Nevertheless, even though the master’s hand is not evident in all of the Gallery’s “Rembrandt” paintings, the images remain striking and compelling.

Widener's and Mellon’s paintings are at the core of the Gallery’s collection of Dutch paintings, but their appearance has changed substantially over the years. The Rembrandts are no longer hung in separate Widener and Mellon galleries but are integrated. Paintings are now carefully lit, and Dutch frames have replaced many of the elegant gold French and English frames that once engulfed the works. Almost all the paintings have been conserved. Relieved of discolored varnish, they have regained a vibrant presence and immediacy that had become dimmed over time. P. A. B. and Joseph Widener and Mellon had selected well—the paintings they acquired were in remarkably good condition, and remain the masterpieces they had believed them to be. Only among the Vermeer and Rembrandt paintings have attribution changes been made. Finally, a number of Dutch and Flemish paintings are hung together to emphasize the interrelated nature of their artistic traditions.

The construction of three cabinet galleries in 1995 had a huge impact on the presentation of Dutch and Flemish paintings. Because of these new spaces, the Gallery is now able to acquire and exhibit small paintings that would have been unsuitable in the large oak-paneled galleries. Were it not for the cabinet galleries, for example, it would not have been feasible to acquire Ambrosius Bosschaert’s remarkable copper, Bouquet of Flowers in a Glass Vase (1621; fig. 11), or Adriaen Coorte’s evocative Still Life with Asparagus and Red Currants (1696; fig. 12), one of many superb paintings acquired in recent years with funds donated by The Lee and Juliet Folger Fund.

The cabinet galleries have also proved to be excellent venues for temporary exhibitions. The ability to display prints, drawings and decorative arts in the wall cases provides an opportunity to enrich our understanding of the paintings and the context in which they were made. For example, in the Pieter Claesz exhibition of 2005, the ewer that Claesz depicted in one of his still lifes was shown next to that painting. Musical instruments similar to those depicted by Judith Leyster accompanied her paintings in the monographic show of 2009. These exhibitions have also prompted a number of generous donations, as, for example, Judith Leyster’s small roundel, Young Boy in Profile (fig. 13), that Mrs. Thomas M. Evans gave at the time of the exhibition.

A steady stream of acquisitions has also given the Gallery’s collection of Dutch art a different look. In the mid-1970s the collection numbered slightly over seventy works, while it presently consists of more than 130 paintings. Even though the Gallery does not aspire to present a complete overview of Dutch art, such as one finds in the Rijksmuseum, many more artists are now represented, and the types and chronological range of paintings are also much greater.[35] As with the Gallery’s core collection, these acquisitions have come as a result of generous donations from private collectors, whether as works of art or as funds designated for a specific purchase. Other paintings have been bought with National Gallery of Art acquisition funds, such as the Patrons’ Permanent Fund.

In the 1970s purchases of Dutch paintings were not easy to make, partly because of lack of funds, and partly because of an overriding sense that the masterpieces that Mellon and the Wideners had collected reflected the best of Dutch art, and nothing needed to be added. The idea of purchasing Dutch art was complicated by the fact that, other than for Rembrandt, Hals, and Vermeer, Dutch painters were commonly described as “little masters.” The National Gallery of Art, I was told, does not collect “little masters.” An effort to introduce some of these painters to the Gallery was made through a loan-exchange program with the Rijksmuseum in the early 1980s: eight “little masters” came to Washington in exchange for a painting by Goya. An increasingly active exhibition program also brought to the Gallery a number of “little masters” as temporary guests. Occasionally, some of these guests stayed, as with Abraham Mignon’s Still Life with Fruit, Fish, and a Nest (fig. 14), which John and Teresa Heinz donated to the Gallery in conjunction with the 1989 exhibition of their remarkable collection of Dutch and Flemish still life paintings.

By the mid 1980s it had become clear that the canon of artists that appealed to Mellon and the Wideners was overly restrictive. Moreover, more flexibility in acquisitions became possible after the Board of Trustees decided to allow the Gallery to bid on paintings at auction (up to a certain price level) without requiring that the works be brought physically to the Board for prior approval. The first acquisition under this new policy was Ludolf Backhuysen’s Ships in Distress off a Rocky Coast fig. 15), which the Gallery bought at Christie’s in London in 1985. This acquisition of a large painting was significant for a number of reasons. Prior to its purchase, the Gallery had no true Dutch marine painting, and for a collection that featured a country that was so dependent on the sea and so adept at depicting it, this lacuna was enormous. Mellon and P. A. B. Widener, moreover, had a predilection for gentle, Arcadian scenes, and this painting introduced a dramatic image of sailors facing death under threatening clouds and in storm-tossed seas.

Other major Dutch paintings acquired at auction have similarly expanded the character of the collection. Among these were Hendrick Goltzius’ The Fall of Man (1616; fig. 16), purchased through the Patrons' Permanent Fund in 1996. Goltzius was not a name familiar to the Wideners and Mellon, or their contemporaries. With the exception of Rembrandt, stories from the Bible or mythology by Dutch artists were of no interest for these collectors: such topics were deemed to be suitable for the sensitivities of Italian or French artists but not the Dutch. Even more radical than purchasing a Goltzius history painting, however, was the fact that it featured two large nudes, which would never have been acceptable to Andrew Mellon. In fact, the classicizing style of The Fall of Man, with its large-scale idealized images of Adam and Eve, was unlike any other image in the collection of Dutch and Flemish paintings, except for Peter Paul Rubens’ Daniel and the Lions’ Den. Today, these two masterpieces hang comfortably together in the same room, a telling reminder of the contacts Goltzius and Rubens had in the 1610s.

Most recent acquisitions have focused in areas where the story of Dutch art is not adequately covered by masterpieces of the Mellon and Widener collections. As previously mentioned, Dutch and Flemish still life painting was severely underrepresented when the National Gallery of Art first opened. Now, through the generosity of private collectors, including Mrs. Paul Mellon, the Gallery is able to exhibit about twenty flower pieces and tabletop still lifes, both large and small. One exceptional painting is Jan van Huysum’s sumptuous Still Life with Flowers and Fruit (c. 1715; fig. 17), donated in 1996 by Philip and Lizanne Cunningham. A different situation existed with Rembrandt. Even though this master was extremely well represented, his works largely existed in a vacuum since the Gallery had very few works by his close contemporaries. In 2006 this situation was largely rectified by the Kaufman Americana Foundation, which donated Jan Lievens’ expressive Bearded Man with a Beret (fig. 18) in honor of George and Linda Kaufman.

Dutch Italianate painting was another area that needed strengthening. Andrew Mellon and P. A. B. and Joseph Widener liked their Dutch paintings to look Dutch, and were not interested in painters who were inspired by Italy or Italian art. The absence of important Italianate paintings was recognized by Robert H. Smith (1928–2009), who served as president of the Board of Trustees from 1993 to 2003, and who was a great supporter of Dutch art. Not only did he advocate that the National Gallery of Art acquire Jan Both’s imposing An Italianate Evening Landscape (fig. 19), but he and his wife, Clarice, donated Nicolaes Berchem’s luminous View of an Italian Port (fig. 20). Recent donations of two works by Cornelis van Poelenburch have further enriched the Gallery’s collection of Italianate painting.

A different issue existed with Haarlem portraiture. The combined interest of Mellon and Widener provided the Gallery with an outstanding collection of portraits by Frans Hals. It is also fortunate to have Judith Leyster’s engaging Self-Portrait (fig. 21), which Mr. and Mrs. Robert Woods Bliss donated in 1949. Nevertheless, a broader view of Haarlem portraiture only occurred in 1998 with the purchase of Johannes Cornelisz Verspronck’s dashing Andries Stilte as a Standard Bearer (1640; fig. 22). The story of Haarlem portraiture was further strengthened with the acquisition of Jan de Bray’s posthumous portrait of his parents, Salomon de Bray and Anna van Westerbaen (fig. 23), one of several important Dutch paintings that Joseph McCrindle donated to the Gallery. De Bray’s stark double profile image has a timeless quality, quite different from the immediacy of Hals’ and Leyster’s portraits. De Bray stipulated in his will that the painting should be given to the city of Haarlem, an indication of the importance he attached to this commemorative portrait.

The challenge of finding Dutch paintings at the level of those that Mellon and the Wideners collected is great: far fewer important works come to the art market today than did in the early twentieth century. Nevertheless, in recent years, great paintings have come on the market as a consequence of Nazi looting during World War II. After the war, a number of those confiscated masterpieces entered museum collections; many of these have now been returned to their rightful heirs. Some families that received these restituted works have, in turn, sold them. As a result, masterpieces previously thought to have belonged to museums have become available for purchase. Fortunately, through the generosity of donors, and the leadership of the Board of Trustees and the Gallery’s current director, Earl Powell, the Gallery has been able to respond to this window of opportunity and acquire two masterpieces that have given new dimensions to the Dutch collection.

The first of these works is Salomon van Ruysdael’s River Landscape with Ferry (1649; fig. 24). Ever since I first saw this masterpiece hanging in the Rijksmuseum in 1969 I had assumed that it belonged to that great museum. It is, after all, the finest work he ever painted, as its imposing composition and atmospheric effects are unmatched in his other works. I later learned, however, that River Landscape with Ferry had been placed at the Rijksmuseum by the Dutch government, which had assumed possession of the painting after World War II. The painting's pre-war owner was Jacques Goudstikker, a prominent Jewish art dealer in Amsterdam who died in 1940 while fleeing to England with his family. After the Nazis took control of his gallery, the painting was confiscated and sent to Hermann Goering. In 2006, the painting was restituted to Goudstikker’s heirs, who then offered it for sale through Christie's. The National Gallery of Art acquired this masterpiece with acquisition funds generously provided by the Patrons' Permanent Fund and The Lee and Juliet Folger Fund.

Hendrick ter Brugghen’s Bagpipe Player (1624; fig. 25) was another restituted masterpiece that the Gallery was able to purchase through the combination of Gallery funds—in this instance, the Paul Mellon Fund, and the enthusiastic support and generosity of Greg and Candy Fazakerley. Ter Brugghen and other Utrecht Caravaggisti had always been notably absent from the Gallery’s collection: such works were not part of the canon admired by Mellon and P. A. B. Widener. They were also not appreciated by John Walker, who could have steered such paintings into the Kress collection, and hence to the Gallery.[36] Until this painting’s restitution from the Wallraf-Richartz Museum in Cologne in 2008, I had believed that acquiring one of Ter Brugghen’s iconic images would be impossible since they reside in museum collections. The museum in Cologne had acquired the painting at a forced sale of the possessions of the Van Klemperer family in Berlin. After it was restituted to the family’s heirs, the painting was offered for sale, and the Gallery acquired it from a consortium of art dealers.

These last two acquisitions involve restituted paintings, but in many ways the most moving story connected to the horrific events of World War II concerns Aelbert Cuyp’s River Landscape with Cows (fig. 26), which belonged to the Petschek family in Aussig, Czechoslovakia. Aware of Nazi intentions, the family fled their homeland in 1938, leaving behind a painted copy of this work on the walls of their home as a show of defiance against Hitler. The family took the unframed Cuyp painting with them as they made their way through France and Spain, eventually reaching Brazil and finally, in 1940, the United States. After the death of their mother in 1986, Elisabeth de Picciotto and Maria Petschek Smith donated this wonderful painting to the National Gallery of Art in appreciation of all that America had done for refugees, including their family, and for “the freedom and opportunities it has afforded to so many throughout its history.”[37]

Their sentiments, so poignantly expressed, have been shared by all of the many donors to the National Gallery of Art since its beginnings in 1941. As one enters John Russell Pope’s magnificent building and wanders through elegantly appointed rooms filled with some of the world’s greatest art treasures, it is impossible not to feel that sense of pride that accompanied the donation of each of the works hanging in the galleries. Andrew Mellon, P. A. B. and Joseph Widener, Samuel H. Kress, and the National Gallery of Art’s other founding members provided an extraordinary foundation for this institution, and, as Mellon envisioned, their example of philanthropy has continued to inspire new generations to join in this legacy. The institution has grown and matured, not only in its collections, but also through its conservation practices, scholarly research, and educational programs, all of which help the Gallery nurture and interpret the treasures entrusted to its care.

Dutch art, of course, is but one component of the story of the National Gallery of Art, but it is an important one. The historical connection between the Dutch and the Americans that so inspired turn-of-the-century collectors remains true and valid today, but the associations are now more nuanced than they were in the past. Cultures have evolved, and our understanding of past societies – including the Netherlands and America – is now quite different than it was. More and a greater variety of Dutch artists painted at an extraordinarily high level than previously imagined. With the introduction of their work into the Gallery’s collection, we gain deeper insights into the Netherlands, its people, and their society. The story, however, is not yet finished and will keep evolving as new artistic treasures come to the National Gallery of Art and join the existing collection.

Notes

[1]This text is based on an essay that appears in the following publication: Holland’s Golden Age in America: Collecting the Art of Rembrandt, Vermeer, and Hals, edited by Esmée Quodbach (New York, 2014). I am extremely grateful to the Center for the History of Collecting at the Frick Art Reference Library, the Frick Collection, New York, which co-published this volume with the Pennsylvania State University Press, for granting permission to include this essay in Dutch Paintings of the Seventeenth Century.

I would like to thank Henriette Rahusen and Jennifer Henel, my colleagues in the department of northern baroque paintings at the National Gallery of Art, for their assistance in preparing this essay which I wrote in 2010.

[2] These words were spoken by Paul Mellon at the opening of the National Gallery of Art on March 17, 1941. Andrew Mellon, his father, had died in August 1937, shortly after construction of the Gallery had begun. For a full account of Mellon’s gift, and the complex law suit over his taxes that unfolded in the latter years of his life, see Philip Kopper, America’s National Gallery of Art: A Gift to the Nation (New York, 1991) and David Cannadine, Mellon: An American Life (New York, 2006), 158–160.

[3] Special arrangements made with Samuel Kress allowed the Gallery to de-accession paintings not deemed worthy of being part of the National Gallery of Art collection. These decisions were largely made in consultation with John Walker. In the late 1940s a program was developed to distribute a great number of paintings to regional museums in the United States. See Marilyn Perry, “The Kress Collection,” in A Gift to America: Masterpieces of European Painting from the Samuel H. Kress Collection (Raleigh, NC, 1994), 13–35.

[4] From P. A. B. Widener, Without Drums (New York, 1940), 57: “Grandfather and Father working together pared the original collection from four hundred and ten pictures of assorted worth down to one hundred outstanding paintings. Each painting in the present collection is the very best which could be obtained of the artist represented. There is no question about any of them.”

[5] For information on this painting and all other Dutch paintings in the collection of the National Gallery of Art prior to 1995, see Arthur K. Wheelock Jr., Dutch Paintings of the Seventeenth Century (Washington, DC, 1995).

[6] Arthur K. Wheelock Jr.,“The Story of Two Vermeer Forgeries,” in Shop Talk: Studies in Honor of Seymour Slive, eds. C. P. Schneider, W. W. Robinson and A. I. Davies (Cambridge, MA, 1995), 271–275. For an argument that the painter of these forgeries was Han van Meegeren, see Jonathan Lopez, The Man Who Made Vermeers: Unvarnishing the Legend of Master Forger Han van Meegeren (Orlando, 2008).

[7] David Cannadine, Mellon: An American Life (New York, 2006).

[8] For Mellon’s relationship to Joseph Duveen, see Meryle Secrest, Duveen: A Life in Art (New York, 2004). In Mellon: An American Life (New York, 2006), David Cannadine notes that Mellon’s first acquisitions around 1900, which consisted mostly of nineteenth-century French paintings and British art, were from Knoedler’s Pittsburgh office. It was at this time, however, that he bought his first seventeenth-century Dutch painting, Aelbert Cuyp’s Herdsman Tending Cattle, now at the National Gallery of Art.

[9] Meryle Secrest, Duveen: A Life in Art (New York, 2004), particularly pages 299–308.

[10] Meryle Secrest, Duveen: A Life in Art (New York, 2004), 302–305.

[11] According to Maygene Daniels, archivist at the National Gallery of Art, Dale admired French impressionist still life paintings and wanted to place them within a broader overview of the still life tradition. The Kalf acquisition, which occurred in 1930, was made in that context. Another still life was added to the collection in 1961 when a flower piece by Jan Davidsz de Heem was purchased.

[12] See Walter Liedtke, “Dutch Paintings in America: The Collectors and Their Ideals,” in Great Dutch Paintings from America, ed. Ben Broos (The Hague, 1990), 31–54. A desire for social prestige, and a competition among peers, both implicit and explicit, motivated all of these collectors.

[13] An excellent sense of the efforts by dealers to place important paintings with their millionaire clients is found in Cynthia Saltzman, Old Masters, New World: America’s Raid on Europe’s Great Pictures 1880-World War I (New York, 2008).

[14] John Smith, A Catalogue Raisonné of the Works of the Most Eminent Dutch, Flemish and French Painters, 9 vols. (London 1829–1842). For John Smith’s influence on English collecting taste, and the character of the National Gallery collection around 1900, see Christopher Brown, “Revising the Canon: The Collector’s Point of View.” Simolius 26 (1998): 201–212.

[15] For an excellent examination of Widener’s collection, see Esmée Quodbach, “‘The Last of the American Versailles’: The Widener collection at Lynnewood Hall,” Simiolus 29 (2002): 42–96. Initially, Widener seems to have relied on the advice of his friends William Elkins (1832–1903) and John G. Johnson (1841–1917) as well as that of the British art dealer Charles Fairfax Murray (1849–1919). Widener’s initial efforts at collecting, which occurred in the late 1880s, were largely directed toward the Barbizon School and British art, and the results turned out to be decidedly mixed. His collection of Italian paintings was also fraught with difficulties and was criticized by Bernard and Mary Berenson in 1904 (see David Allan Brown, Berenson and the Connoisseurship of Italian Painting, (Washington, DC, 1979).

[16] Widener acquired a number of questionable Dutch paintings from Leo Nardus. (See Jonathan Lopez, “Gross False Pretences,” Apollo 347 (December 2007): 76–83). Eventually P. A. B. Widener and his son, Joseph, realized that the attributions of many of these works, including three purported Vermeer paintings, were wrong, and returned them to Nardus. Widener also invited the Dutch art historian Cornelius Hofstede de Groot to come to assess his collection. A catalog of the Widener collection as it existed around 1900, with annotations Hofstede de Groot dated 1908, is in the library of the National Gallery of Art.

[17] A large number of works were sold in the first decades of the twentieth century, often as part of a trade to acquire better works of art. For example, in 1908, as part of the purchase price for three Van Dyck paintings, Widener traded in fifty-two paintings. See Cynthia Saltzman, Old Masters, New World: America’s Raid on Europe’s Great Pictures 1880–World War I (New York, 2008). According to Widener’s later curator, Willem Valentiner, 150 paintings were eventually purged from the collection (see Wilhelm R. Valentiner “Diary from My First American Years,” Art News 58 [April 1959]: 51–52). Some of the paintings de-accessioned in these years, including still lifes, may have been sold because they did not conform to the contemporary canon of Dutch art. See also W. Martin, Alt-Hollandische Bilder (Sammeln/Bestimmen/Konservieren), 2nd ed. (Berlin, 1921), 18–19, who commends Widener for his willingness to review his collection and improve upon its quality.

[18] See Arthur K. Wheelock Jr., Dutch Paintings of the Seventeenth Century (Washington, DC, 1995), for Widener’s trip to Russia in 1909. See also Cynthia Saltzman,Old Masters, New World: America’s Raid on Europe’s Great Pictures 1880–World War I (New York, 2008), 206, for negotiations in Paris in 1908 for three Genoese Van Dyck paintings.

[19] See Annette Stott, Holland Mania: The Unknown Dutch Period in American Art and Culture (New York, 1998) for a fascinating overview of the appeal of The Netherlands for contemporary American artists, and for the artist colonies that they visited. See also Annette Stott and Holly Koons McCullough, Dutch Utopia: American Artists in the Netherlands, 1880–1914 (Savannah, GA, 2009).

[20] John Lothrop Motley, The Rise of the Dutch Republic: A History, vol. 1 (New York, 1855).

[21] See Douglas Campbell, The Puritan in Holland, England and America: An Introduction to American History, 2 vols. (New York, 1893), and William Elliot Griffis,Brave Little Holland and What She Taught Us (Boston and New York, 1894). Annette Stott, Holland Mania: The Unknown Dutch Period in American Art and Culture (New York, 1998), 78–89, notes that the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution, freedom of education, and freedom of worship were all seen as deriving from Dutch precedents.

[22] At this time Widener also set in motion plans for architect Horace Trumbauer (1868–1938) to design and build Lynnewood Hall, the enormous Georgian revival-style mansion in Elkins Park that would soon house Widener’s collection of paintings and decorative arts.

[23] Widener also acquired in that year four other major Dutch paintings that he eventually sold, including a Jan van de Cappelle, an Aert van der Neer, a Jan Steen (which is now at the Metropolitan Museum of Art), and a Willem van de Velde the Younger from Colnaghi, and a Simon de Vlieger from Agnew. In that year he also bought a number of important paintings by artists of different schools that were eventually donated to the National Gallery of Art: a Van Dyck (The Prefect Raffaele Raggi) from Sedelmeyer, a Manet (The Dead Toreador) from Cottier and Co., a Turner (The Junction of the Thames and the Medway) from Wallis and Son, and a Murillo (Two Women at a Window) from Stephen T. Gooden. He also bought a “Velasquez” from Gooden that turned out to be a reduced copy of a painting in the Prado. This painting was later sold.

[24] Sedelmeyer was at that time sponsoring Bode’s efforts to publish a corpus of Rembrandt’s paintings (Wilhelm von Bode, Rembrandt und seine Zeitgenossen: Charakterbilder der grossen Meister der Hollandischen und Vlamischen Malerschule im siebzehnten Jahrhundert [Leipzig, 1906]). Bode also had close ties to Colnaghi, which was transformed as an organization in 1894. In that year a partnership was formed between William McKay, Otto Gutekunst, and Edmond Deprez, and the gallery began to shift its focus from prints and drawings to old master paintings. For Bode’s close relationship with McKay and Goodekunst, see Jeremy Howard, “A Masterly Old Master Dealer of the Gilded Age: Otto Gutekunst and Colnaghi,” in Colnaghi Established 1760: The History, ed. Jeremy Howard (London, 2010), 12–19.

[25] Wilhelm von Bode, Mein Leben, 2 vols. (1910–1929); reprint Thomas W. Gaehtgens and Barbara Paul, eds. (Berlin, 1997).

[26] John Gage, Color in Turner: Poetry and Truth (New York, 1969).

[27] Wilhelm von Bode, Rembrandt und seine Zeitgenossen: Charakterbilder der grossen Meister der Hollandischen und Vlamischen Malerschule im siebzehnten Jahrhundert(Leipzig, 1906).

[28] For a discussion of this acquisition, see Arthur K. Wheelock Jr., Dutch Paintings of the Seventeenth Century (Washington, DC, 1995).

[29] P. A. B. Widener, Without Drums (New York, 1940).

[30] The fact that the English instituted death duties in 1911 meant that a number of masterpieces were then being sold by British aristocrats.

[31] The other significant acquisitions during this period were Judith Leyster’s self-portrait, given by the Bliss family in 1949; a Gerrit Dou from the Timken collection in 1960; two paintings by Jacob van Ruisdael, one given by Rupert L. Joseph in 1960 and one from the Kress collection in 1961; a still life by Jan Davidsz de Heem, purchased in 1961; a winter scene by Hendrick Avercamp, bought in 1967; and a landscape by Jan van der Heyden, acquired in 1968.

[32] Abraham Bredius, Rembrandt: The Complete Edition of the Paintings, rev. by Horst Gerson (London, 1969).

[33] National Gallery of Art, Rembrandt in the National Gallery of Art (Washington, DC, 1969).

[34] Arthur K. Wheelock Jr., Dutch Paintings of the Seventeenth Century (Washington, DC, 1995).

[35] Only two of these acquisitions are paintings by artists represented in the Widener/Mellon gifts, a landscape by Aelbert Cuyp (1986.70.1) and a genre scene by Isaac van Ostade (1991.64.1).

[36] Edgar Peters Bowron, “The Kress Brothers and Their ‘Bucolic Pictures’: The Creation of an Italian Baroque Collection,” in A Gift to America: Masterpieces of European Painting from the Samuel H. Kress Collection (Raleigh, NC, 1994), 49–54.

[37] This summary of the history of the Cuyp painting is taken from the personal account of Maria Petschek Smith and Elizabeth de Picciotto, which they wrote in 2010 (NGA curatorial files).

*This text is based on an essay that appears in the following publication: Holland’s Golden Age in America: Collecting the Art of Rembrandt, Vermeer, and Hals. Edited by Esmée Quodbach. New York: The Frick Collection; University Park: The Pennsylvania State University Press, 2014.

To cite: Arthur K. Wheelock Jr., “A History of the Dutch Painting Collection at the National Gallery of Art,” in Dutch Paintings of the Seventeenth Century, NGA Online Editions (Washington, 2014).

Fig. 1 Rembrandt van Rijn, The Mill, 1645/1648, oil on canvas, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Widener Collection, 1942.9.62

Fig. 2 Rembrandt van Rijn, Saskia van Uylenburgh, the Wife of the Artist, probably begun 1634/1635 and completed 1638/1640, oil on panel, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Widener Collection, 1942.9.71

Fig. 3 Nicholaes Maes, An Old Woman Dozing over a Book, c. 1655, oil on canvas, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Andrew W. Mellon Collection, 1937.1.63

Fig. 4 Aelbert Cuyp, Lady and Gentleman on Horseback, c. 1655, reworked 1660/1665, oil on canvas, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Widener Collection, 1942.9.15

Fig. 5 Meindert Hobbema, The Travelers, c. 166[2?], oil on canvas, National Gallery of Art, Widener Collection, 1942.9.31

Fig. 6 Pieter de Hooch, The Bedroom, 1658/1660, oil on canvas, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Widener Collection, 1942.9.33

Fig. 7 Jacob van Ruisdael, Forest Scene, c. 1655, oil on canvas, National Gallery of Art, Widener Collection, 1942.9.80

Fig. 8 Rembrandt Workshop, Portrait of Rembrandt, 1650, oil on canvas, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Widener Collection, 1942.9.70

Fig. 9 Johannes Vermeer, Woman Holding a Balance, c. 1664, oil on canvas, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Widener Collection, 1942.9.97

Fig. 10 - Joachim Wtewael, Moses Striking the Rock, 1624, oil on panel, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Ailsa Mellon Bruce Fund, 1972.11.1

Fig. 11 Ambrosius Bosschaert, Bouquet of Flowers in a Glass Vase, 1621, oil on copper, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Patrons' Permanent Fund and New Century Fund, 1996.35.1

Fig. 12 Adriaen Coorte, Still Life with Asparagus and Red Currants, 1696, oil on canvas, National Gallery of Art, The Lee and Juliet Folger Fund, 2002.122.1

Fig. 13 Judith Leyster, Young Boy in Profile, c. 1630, oil on panel, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of Mrs. Thomas M. Evans, 2009.113.1

Fig. 14 Abraham Mignon, Still Life with Fruit, Fish, and a Nest, c. 1675, oil on canvas, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. H. John Heinz III, 1989.23.1

Fig. 15 Ludolf Backhuysen, Ships in Distress off a Rocky Coast, 1667, oil on canvas, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Ailsa Mellon Bruce Fund, 1985.29.1

Fig. 16 Hendrik Goltzius, The Fall of Man, 1616, oil on canvas, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Patrons' Permanent Fund, 1996.34.1

Fig. 17 Jan van Huysum, Still Life with Flowers and Fruit, c. 1715, oil on panel, National Gallery of Art, Patrons' Permanent Fund and Gift of Philip and Lizanne Cunningham, 1996.80.1

Fig. 18 Jan Lievens, Bearded Man with a Beret, c. 1630, oil on panel, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of George M. and Linda H. Kaufman, 2006.172.1

Fig. 19 Jan Both, An Italianate Evening Landscape, c. 1650, oil on canvas, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Patrons' Permanent Fund, 2000.91.1

Fig. 20 Nicholaes Pietersz Berchem, View of an Italian Port, early 1660s, oil on canvas, Naitonal Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of Robert H. and Clarice Smith, in Honor of the 50th Anniversary of the National Gallery of Art, 1990.62.1

Fig. 21 Judith Leyster, Self-Portrait, c. 1630, oil on canvas, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Robert Woods Bliss, 1949.6.1

Fig. 22 Johannes Cornelisz Verspronck, Andries Stilte as a Standard Bearer, 1640, oil on canvas, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Patrons' Permanent Fund, 1998.13.1

Fig. 23 Jan de Bray, Portrait of the Artist's Parents, Salomon de Bray and Anna Westerbaen, 1664, oil on panel, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of Joseph F. McCrindle in memory of his grandparents, Mr. and Mrs. J. F. Feder, 2001.86.1

Fig. 24 Salomon van Ruysdael, River Landscape with Ferry, 1649, oil on canvas, Patrons' Permanent Fund and The Lee and Juliet Folger Fund. This acquisition was made possible through the generosity of the family of Jacques Goudstikker, in his memory, 2007.116.1

Fig. 25 Hendrick ter Brugghen, Bagpipe Player, 1624, oil on canvas, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Paul Mellon Fund and Greg and Candy Fazakerley Fund, 2009.24.1

Fig. 26 Aelbert Cuyp, River Landscape with Cows, 1645/1650, oil on panel, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of Family Petschek (Aussig), 1986.70.1