Winslow Homer in the National Gallery of Art

Introduction

From the late 1850s until his death in 1910, Winslow Homer produced a body of work distinguished by its thoughtful expression and its independence from artistic conventions. A man of multiple talents, Homer excelled equally in the arts of illustration, oil painting, and watercolor. Many of his works—depictions of children at play and in school, of farm girls attending to their work, hunters and their prey—have become classic images of nineteenth-century American life. Others speak to more universal themes such as the primal relationship of man to nature.

Highlighting a wide and representative range of Homer's art, this Web feature traces his extraordinary career from the battlefields, farmland, and coastal villages of America, to the North Sea fishing village of Cullercoats, the rocky coast of Maine, the Adirondacks, and the Caribbean, offering viewers the opportunity to experience and appreciate the breadth of his remarkable artistic achievement.

More than fifty paintings, drawings, prints, and watercolors in the Gallery's Homer collection will be on view at the National Gallery of Art, East Building Mezzanine, from July 3, 2005 – February 26, 2006.

On the Trail, c. 1892, watercolor over graphite, Gift of Ruth K. Henschel in memory of her husband, Charles R. Henschel, 1975.92.12

Winslow Homer was born in Boston, the second of three sons of Henrietta Benson, an amateur watercolorist, and Charles Savage Homer, a hardware importer. As a young man, he was apprenticed to a commercial lithographer for two years before becoming a freelance illustrator in 1857. Soon he was a major contributor to such popular magazines as Harper’s Weekly; in 1859 he moved to New York to be closer to the publishers that commissioned his illustrations and to pursue his ambitions as a painter.

Napoleon Sarony, Photograph: Winslow Homer taken in N.Y., 1880 (detail), 1880, Bowdoin College Museum of Art, Brunswick, Maine, Gift of the Homer Family

Sent by Harper’s to the front as an artist-correspondent during the Civil War, Homer captured the essential modernity of the conflict in such images as The Army of the Potomac—A Sharp-Shooter on Picket Duty. While traditional battle pictures usually depicted, in the words of a contemporary, “long lines…led on by generals in cocked hats,” Homer instead shows a solitary figure who, using new rifle technology, is able to fire from a distance and remain unseen by his target.

The subject of this engraving is based on Homer's first oil painting. An emblematic image of the Civil War, the lone figure of a sharpshooter reveals the changing nature of modern warfare. With new, mass-produced weapons such as rifled muskets, killing became distant, impersonal, and efficiently deadly. Despite public admiration for sharpshooters' skill, ordinary soldiers looked upon them as cold-blooded, mechanical killers. Many years after the war, Homer wrote an old friend, "I looked through one of their rifles once....The...impression struck me as being as near murder as anything I could think of in connection with the army and I always had a horror of that branch of the service."

After Winslow Homer, The Army of the Potomac - A Sharp-Shooter on Picket Duty, published 1862, wood engraving on newsprint, Avalon Fund, 1986.31.75

Homer drew upon his experience of the war to create his first oil paintings, many of them scenes of camp life that illuminate the physical and psychological plight of ordinary soldiers. He received national acclaim for these early works, both for the strength of his technique and the candor of his subjects.

This picture, exhibited in New York in 1863, was enthusiastically admired and quickly sold. The title refers to the song frequently played by the Union regimental band, a piece that no doubt inspired homesickness and longing in the infantry men who listened to it.

But the title also refers to the soldiers' present "home," shown with all of its domestic details—a small pot on a smoky fire, hard biscuits on a tin plate—that Homer, who did the cooking and washing when he was on the front, knew intimately, and that, with surely intended irony, was far from "sweet."

Home, Sweet Home, c. 1863, oil on canvas, Patrons' Permanent Fund, 1997.72.1

In the late 1860s, Homer turned to life in rural and coastal America for his subject matter. His postwar work employs a brighter palette and freer brushwork, and shows his interest in the fleeting effects of light and atmosphere. The freshness of his touch is evident in the brilliant light and delicate coloration of The Dinner Horn (Blowing the Horn at Seaside). The young woman sounding the call to dinner appears in several other paintings and relates to one of Homer’s favorite motifs throughout the 1870s: the solitary female figure, often absorbed in thought or work.

The Dinner Horn (Blowing the Horn at Seaside), 1870, oil on canvas, Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Paul Mellon, 1994.59.2

Many of Homer's paintings show self-assured, independent, working women, such as the teacher featured prominently in The Red School House. The one-room schoolhouse in the background appears in a number of Homer's works from this time, including Snap the Whip, one of his most beloved images.

The Red School House, 1873, oil on canvas, Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Paul Mellon, 1985.64.21

Childhood, an important theme in the work of such contemporary American writers as Louisa May Alcott and Mark Twain, became Homer’s principal subject in the early 1870s. Pictures of children gathered in a one-room schoolhouse, playing in the countryside, or sitting on the beach on a summer day suited the postwar nostalgia for the presumed simplicity and innocence of a bygone era.

Lagarde, American (?), active c. 1873, Snap-the-Whip, published 1873, wood engraving on newsprint, Avalon Fund, 1986.31.268

Homer’s early works, while mainly set outdoors, are almost all figure paintings. This was a conspicuous departure from the type of pure landscape that dominated nineteenth-century American art. Homer spent the summer of 1873 in Gloucester, Massachusetts, where he painted this family of a fisherman awaiting his return. The exuberance suggested by the title—first given when an engraving of the painting was published in Harper's Weekly in 1873—is tempered by the meditative air of the still, silhouetted figures. The mother faces away from the sea, while the young boy scans a horizon that yields no sign of an approaching boat. Instead of depicting a celebratory narrative of homecoming, Homer captures the more ambiguous moment of watching and waiting. He would have been acutely aware of this aspect of the lives of fishermen's families, for Gloucester experienced a significant loss of life due to tragedies at sea during his stay.

Dad's Coming!, 1873, oil on wood, Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Paul Mellon, 2001.97.1

One of Homer's most popular paintings, Breezing Up was first exhibited in 1876, the year of America's centenary celebration. Critics hailed the work for its freshness and energy. Amid the general climate of optimism and great expectations for the future, some sensed an even larger meaning in the scene—one writer declared that "the skipper's young American son, gazing brightly off to the illimitable horizon [is a symbol of] our country's quiet valor, hearty cheer, and sublime ignorance of bad luck."

Breezing Up (A Fair Wind), 1873-1876, oil on canvas, Gift of the W. L. and May T. Mellon Foundation, 1943.13.1

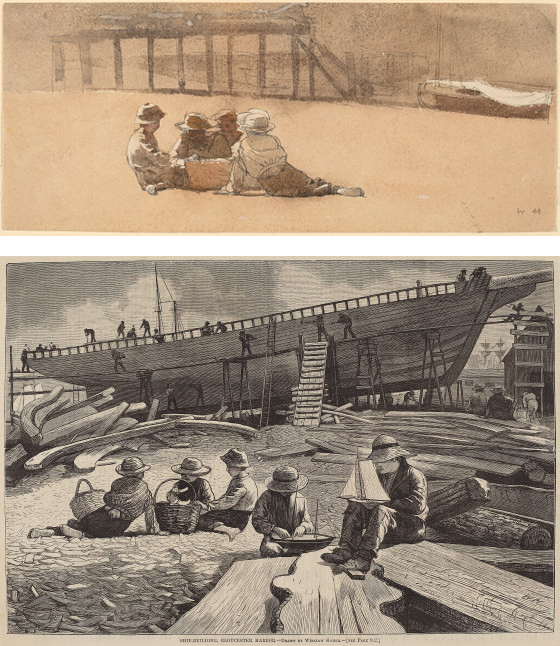

Homer often assembled his prints from diverse sources. In Ship-Building, Gloucester Harbor, he brought together from four different works, including two oil paintings, a drawing, and a watercolor of four boys, who appear in reverse. Children often gathered in the shipyard after school, to collect chips for kindling, build chip houses, observe the workmen, and to carve and rig miniature vessels. The text that acccompanied the print in Harper's Weekly described the picture as "interesting not only as a work of art, but as a suggestion of the renewed enterprise and activity which are beginning to manifest themselves in American ship-yards. All along our immense line of coast may be seen indications which awaken the hope that America will soon resume her former supremacy in building ships."

(top) Four Boys on a Beach, c. 1873, graphite with watercolor and gouache on wove paper, John Davis Hatch Collection, Andrew W. Mellon Fund 1979.19.1

(bottom) After Winslow Homer, Ship-Building, Gloucester Harbor, published 1873, wood engraving on newsprint, Avalon Fund, 1986.31.119

Homer had been working as an artist for nearly two decades when, in the words of one contemporary critic, he took "a sudden and desperate plunge into watercolor painting." Long the domain of amateur painters, watercolors had gained professional respectability in 1866 with the formation of the American Water Color Society. Homer recognized their potential for profit—for he could produce and sell them quickly—but he also liked the way watercolor allowed him to experiment more easily than oil.

He created his first series in Gloucester, Massachusetts, in 1873, and by the time he painted his last watercolor, in 1905, he had become the unrivaled master of the medium in America.

Some critics found fault in Homer's early watercolors for their apparent lack of finish and their commonplace subject matter. Yet Homer valued them from the start. He priced The Sick Chicken, a delicate work that demonstrates his early technique of filling in outlined forms with washes of color, at the steep price of one hundred dollars.

The Sick Chicken, 1874, watercolor, gouache, and graphite on wove paper, Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Paul Mellon, 1994.59.21

The size of this watercolor and its highly finished state suggest that Homer was attempting to create what English artists called "exhibition watercolors"—works that were intended to rival the aesthetic power and impact of oil paintings.

Homer often reused the same figures in different scenes. The girl in this work appeared previously in a drawing, an oil painting, and two watercolors. More generally, she is related to the many solitary figures of women that appear in Homer's work especially during the 1870s, including The Sick Chicken and Fresh Eggs.

The Milk Maid, 1878, watercolor over graphite, Gift of Ruth K. Henschel in memory of her husband, Charles R. Henschel, 1975.92.11

For a short period in the late 1870s, a decorative quality became evident in Homer's art. Blackboard, which continues the theme of elementary education found in many of his oils, epitomizes this development. The studied elegance of the work's design derives in part from its monochromatic palette and in part from the geometric patterning found in the bands of color in the background, the checkered apron, and the marks on the board.

The marks on the blackboard puzzled scholars for many years. They now have been identified as belonging to a method of drawing instruction popular in American schools in the 1870s. In their earliest lessons, young children were taught to draw by forming simple combinations of lines, as seen on the blackboard here. Rather than being a polite accomplishment, drawing was viewed as having a practical application, playing a valuable role in industrial design. Homer playfully signed the blackboard in its lower-right corner as though with chalk.

Blackboard, 1877, watercolor on wove paper, Gift of Jo Ann and Julian Ganz, Jr., in Honor of the 50th Anniversary of the National Gallery of Art, 1990.60.1

Homer spent several months during the summer and late fall of 1878 at Houghton Farm, the country residence of a patron in Mountainville, New York. There he created dozens of watercolors of farm girls and boys playing and pursuing various tasks, including Warm Afternoon. Painted quickly and often outdoors, these watercolors present idyllic scenes of rural life that follow in the European tradition of pastoral painting.

(left) Warm Afternoon (Shepherdess), 1878, watercolor, gouache, and graphite on gray-green paper faded to brown, Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Paul Mellon, 1994.59.24

(right) Girl with Hay Rake, 1878, watercolor, Gift of Ruth K. Henschel in memory of her husband, Charles R. Henschel, 1975.92.17

These graceful depictions of boys and girls frolicking in the outdoors are fluidly painted and transparently colored, conveying a sense of lightness and spontaneity.

On the Stile, c. 1878, watercolor, gouache, and graphite on wove paper, Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Paul Mellon, 1994.59.23

On the Fence, 1878, watercolor, gouache, and graphite on wove paper, Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Paul Mellon, 1994.59.22

In March 1881, Homer sailed from New York to England, where he spent twenty months in the small fishing villlage of Cullercoats on the North Sea.

Homer painted primarily in watercolor while in Cullercoats. Numerous preliminary studies and the careful planning evident in these works reflect his aspiration to construct a more classical, stable art of seriousness and gravity.

Mending the Nets, 1882, watercolor and gouache over graphite, Bequest of Julia B. Engel, 1984.58.3

The fisherwomen of Cullercoats were a source of constant inspiration to Homer during his stay in England. Admiring their strength and endurance, he endowed them with a sense of calm dignity and grace. Sparrow Hall, one of a few finished oil paintings produced in Cullercoats, depicts women knitting or darning near the entrance to a seventeenth-century cottage, the oldest house in the village. The children, as well as the array of baskets, barrels, crates, and floats scattered about the scene, serve as reminders of the women's innumerable responsibilities: keeping house, tending children, repairing nets, gathering bait, and cleaning fish. On the steps, a girl protectively steadies a younger child who dangles a bit of blue yarn in front of a calico cat. Sparrow Hall, wonderfully conceived, brightly colored, and superbly painted, stands very high among the Cullercoats works, and indeed among Homer's images from any period.

Sparrow Hall, c. 1881-1882, oil on canvas, John Wilmerding Collection

Homer's Cullercoats women have often been called heroic, and, although he may have idealized them somewhat, the stern facts of their lives clearly instilled in them great strength and courage. Popular literature of the period depicted the fisherwomen of the North Sea region as uninhibited beauties who exemplified morality and intellectual honesty, a fitting subject for a high and profound art based on contemporary life. Homer remarked, "There were none like them in my country."

Girl Carrying a Basket, 1882, watercolor over graphite, Gift of Ruth K. Henschel in memory of her husband, Charles R. Henschel, 1975.92.4

Homer returned to New York in 1882 and faced the challenge of finding a theme as compelling as that which had occupied him in Cullercoats. Homer had almost always set up an emphatic juxtaposition between the role of women on the shore and that of the men on the sea. As the women determinedly went about their own business, confronted with the inexorable prospect of separation and loss, the men faced tangible physical peril in their constant battle with the elements. In the paintings (and subsequent graphic depictions) of the 1880s, Homer occasionally merged the two themes. The etching Saved, a powerful, highly classicized representation of herioic struggle is based on Homer's 1884 oil painting The Life Line. The wet drapery clinging to the woman's solid form, the anonymity of the rescuer, whose face has been obscured by the scarf as wind and waves swirl about them, all help to convey the sense of physical and emotional exhaustion and the protagonist's heroic effort to triumph over nature's fury.

This remarkably fertile period in Homer's career brought him great critical acclaim. The Life Line was an immediate success, but Homer's work held little commercial appeal. Its striking composition and strong dramatic mood did not match the prevailing aesthetic taste. After viewing Homer's work in a National Academy exhibition, one critic remarked that his paintings had a "rude vigor and grim force that is almost a tonic in the midst of the namby-pambyism of many of the other pictures on display."

Saved, 1889, etching, Gift of John W. Beatty, Jr., 1964.4.10

Eight Bells, one of Homer's best-known paintings and the last of the series of great sea pictures that had commenced with The Life Line three years earlier, was completed in 1886 but not shown until 1888. The title refers to the sounding of eight bells done at the hours of four, eight, and twelve a.m. and p.m. Two sailors dominate the foreground, but the details of the ship and its riggings have been minimized. In the etching above, one of his finest, Homer has de-emphasized the background rigging and sky even further to underscore the figures' monumentality.

Homer's depiction seems to transcend "mere realism" and reveal an element of heroism in the mundane activities of his protagonists. A contemporary critic noted that the artist "has caught the color and motion of the greenish waves, white-capped and rolling, the strength of the dark clouds broken with a rift of sunlight, and the sturdy, manly character of the sailors at the rail. In short, he has seen and told in a strong painter's manner what there was of beauty and interest in the scene."

Eight Bells, 1887, etching, Gift of John W. Beatty, Jr., 1964.4.7

Hauling in the Nets, 1887, watercolor over graphite, Gift of Ruth K. Henschel in memory of her husband, Charles R. Henschel, 1975.92.6

Homer was drawn to the starkly beautiful scenery of the peninsula of Prout's Neck, Maine, settling permenantly there in 1883. Working in watercolor, he began recording the wild power of the sea in various conditions of light and weather, as in this picture of waves breaking against the rugged shore in a dramatic spray of foam. It is one of Homer's first pure marine pictures, without the addition of figures or narrative. This depiction of the elemental forces of nature is an early indication of the artist's primary pictorial concern in his later years. A friend later recalled Homer's attraction to inclement weather: "[W]hen I knew him he was comparatively indifferent to the ordinary and peaceful aspects of the ocean....But when the lowering clouds gathered above the horizon, and tumultuous waves ran along the rockbound coast and up the shelving, precipitous rocks, his interest became intense."

Incoming Tide, Scarboro, Maine, 1883, watercolor, Gift of Ruth K. Henschel in memory of her husband, Charles R. Henschel, 1975.92.8

To escape the harsh Maine winters, Homer began traveling in 1884 to the tropics (Florida, Cuba, the Bahamas, and Bermuda) where, in response to the extraordinary light and color, he created dazzling watercolors distinguished by their spontaneity, freshness, and informal compositions.

Homer traveled to Nassau in the winter of 1884–1885 at the request of Century Magazine, which commissioned illustrations for an article on the popular tourist destination. There Homer executed more than thirty watercolors whose subjects are representative of the scenery of the island and lives of its citizens; however, his greater interest was in capturing the light and atmosphere of the region.

Native Huts, Nassau, 1885, watercolor, graphite, and gouache on wove paper, Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Paul Mellon, 1994.59.20

In scenes of sun-drenched harbors and shores, Homer often left parts of the white paper exposed to give a sense of the brilliant atmosphere. He painted at least nineteen watercolors in Bermuda, a place he visited twice beginning in 1899. He believed them to be "as good work...as I ever did." They reveal—especially in their fluid washes—the consummate mastery of the medium that Homer had achieved by this point in his career. Homer generally preferred the blue skies and white clouds typical of the island's climate. Only occasionally, as in the remarkable The Coming Storm, did he portray ominous weather.

Salt Kettle, Bermuda, 1899, watercolor over graphite, Gift of Ruth K. Henschel in memory of her husband, Charles R. Henschel, 1975.92.15

An avid fisherman, Homer often visited the Adirondack region of upstate New York, where he made many of his finest and most moving paintings. Using watercolor as his principal medium, he recorded the various pursuits of fishermen and hunters.

Casting, Number Two, 1894, watercolor over graphite, Gift of Ruth K. Henschel in memory of her husband, Charles R. Henschel, 1975.92.2

These works celebrate the pleasures and beauty of life in the Adirondacks but also confront the more brutal realities of hunting. In one series, Homer depicted a practice called hounding, in which dogs were used to drive deer into a lake.

A Good Shot, Adirondacks, 1892, watercolor, Gift of Ruth K. Henschel in memory of her husband, Charles R. Henschel, 1975.92.5

Once in the lake, the deer would be clubbed, shot, or drowned easily by hunters in boats. In Sketch for "Hound and Hunter," a young boy struggles to secure a dead deer while also attending to his dog. It was an unusual subject that many found disturbing; critics mistakenly believed that the hunter here was struggling to drown a live deer when in fact, as Homer explained, the deer was already dead.

Sketch for "Hound and Hunter", 1892, watercolor on wove paper, Gift of Ruth K. Henschel in memory of her husband, Charles R. Henschel, 1975.92.7

Homer considered the oil version of Hound and Hunter a "great work" and described the pains he took in painting it: "Did you notice the boy's hands–all sunburnt; the wrists somewhat sunburnt, but not as brown as his hands; and the bit of forearm where his sleeve is pulled back but not sunburnt at all? I spent more than a week painting those hands."

Hound and Hunter, 1892, oil on canvas, Gift of Stephen C. Clark, 1947.11.1

The watercolors Homer produced in Key West in 1903 focus on the graceful white sailing vessels that filled the harbor and plied the local waters. Key West, Hauling Anchor, with its white boat, red-shirted crew, and blue sea reveals Homer's ability to create powerful images using simple pictorial elements. The remarkable confidence and freedom of his handling, with details convincingly suggested but not literally described, make the Key West watercolors some of his most vibrant.

Key West, Hauling Anchor, 1903, watercolor over graphite, Gift of Ruth K. Henschel in memory of her husband, Charles R. Henschel, 1975.92.9

During the last decade of his life, Homer made four visits to Florida. An avid angler, he spent much of his time on these trips fishing rather than painting. He declared the fishing in Homosassa, located off the Gulf of Mexico, "the best in America." Many of the Homosassa watercolors, such as this one, depict the black swath of jungle just beyond the waters where Homer and others fished. The Florida pictures of 1903 to 1905 would be Homer's final series of watercolors. After that, he painted only in oil.

Red Shirt, Homosassa, Florida, 1904, watercolor over graphite, Gift of Ruth K. Henschel in memory of her husband, Charles R. Henschel, 1975.92.13

Homer painted less frequently in the last decade of his life. The paintings he did produce, deepened by intimations of mortality, include some of the most complex pictures of his career.

Right and Left, one of Homer's last paintings, is at once a sporting picture and a tragic reflection on life and death. The title refers to the act of shooting the ducks successivelly with separate barrels of a shotgun. The red flash and billowing gray smoke barely visible at the middle left indicate that a hunter has just fired at the pair of goldeneye ducks. The picture captures the moment but leaves important questions unresolved. Has the rifle hit its mark? If so, does the downward plunge of the bird on the right indicate that it has been hit, or is it diving to escape? The duck on the left seems frozen, but that stasis does not necessarily reveal its physical condition. And consider the precarious position in which Homer has placed the viewer, observing the scene while apparently hovering in mid-air, at one with the threatened creatures—and directly in the path of the oncoming shotgun blast. With its ambiguous message, unconventional point of view, and diverse sources of inspiration ranging from Japanese art to popular hunting imagery, this painting summarizes the creative complexity of Homer's late style.

Although Winslow Homer avoided any discussion of the meaning of his art, the progression of his creative life attests to the presence of a rigorous, principled mind. Continuously refining his artistic efforts, Homer created work that was not only powerful in aesthetic terms but also movingly profound. Acclaimed at his death for his extraordinary achievements, Homer remains today among the most respected and admired figures in the history of American art.

Right and Left, 1909, oil on canvas, Gift of the Avalon Foundation, 1951.8.1

The Winslow Homer Web feature was designed and produced by Donna Mann and edited by Amanda Sparrow. The text has been compiled from various Gallery sources, including exhibition brochures, catalogue essays, and wall texts written by Charles M. Brock and Franklin Kelly in the Department of American and British Paintings and Margaret Doyle in the Department of Exhibition Programs. The video program excerpted here was produced by the Division of Education. Thanks to Charles Brock, Franklin Kelly, Margaret Doyle, Barbara Moore, Amy Lewis, Rachel Richards, Leo Kasun, the Department of Imaging and Visual Services, and the Publishing Office for their assistance with this project.

Signature in Palette, undated, pen and brown ink on paper, John Davis Hatch Collection