The Unfinished Print

Introduction

When does a work of art achieve aesthetic resolution, and when does it fall short? Artists, collectors and theorists since the Renaissance have regarded this question as both problematic and central to understanding the artistic endeavor. For reasons inherent to the medium, prints claim a special place in this history. Over the course of several centuries artists were increasingly apt to retain and distribute prints at various stages in their making. Experiments with differing states and specially tailored impressions encouraged a fascination with degrees of finish in printmaking that challenged the very idea of aesthetic completion. This exhibition chronicles the complex workings of the artistic imagination revealed by the unfinished print and the changing estimation of artistic process that it provoked. Despite its implication for the rise of modernism, this development has never before been considered across its full historical sweep.

Workshop of Andrea Mantegna, Italian, c. 1431 - 1506, The Adoration of the Magi (Virgin in the Grotto), c. 1475/1480, engraving, Rosenwald Collection, 1943.3.1329

Making a print typically entails working up a copperplate or a woodblock in stages and taking readings of the image in progress. Such impressions are usually termed "proof states," although this example was taken from a plate that, as far as we know, was never actually completed. The fact that it was eventually printed and distributed testifies to the celebrity granted Mantegna by later generations.

Every intentional alteration of a plate is conventionally designated as a separate state. This is indicated by Roman numerals. For example, "state i/vii" identifies the first of seven known states. When no state is indicated it means this is the only one recorded, or that the evidence of surviving impressions is insufficient to make a clear determination.

Workshop of Andrea Mantegna, Italian, c. 1431 - 1506, The Adoration of the Magi (Virgin in the Grotto), c. 1475/1480, engraving, Rosenwald Collection, 1943.3.1329

Etchings as Drawings

During the 1510s Italian and German printmakers began to develop the technique of etching. A steel or copperplate is coated with varnish, paint, or wax. This is known as the "etching ground." The artist then draws with a stylus, scraping through the ground to the metal surface. When the plate is bathed in acid the exposed lines are bitten away to create channels for the printing ink. Unlike the demanding and highly specialized skill of engraving, making an etching is comparable to the more familiar practice of drawing. Hence, the technique was readily accessible to the draftsman and perfectly adapted to replicating a drawing style. Because of the relative ease in execution artists began to use etching as a means of distributing much more informal expressions of their ideas. In this respect etching played an important role in generating a taste for drawings as works of art. From the beginning we find etchings that are highly experimental, and many that reflect pictorial inventions of a spontaneous and seemingly unfinished character.

(left) Sir Anthony van Dyck, Flemish, 1599 - 1641, Self-Portrait, probably 1626/1641, etching, State i/vii, Rosenwald Collection, 1943.3.8250

(right) Sir Anthony van Dyck, Flemish, 1599 - 1641, and Jacobus Neeffs, Flemish, 1610 - 1660 or after, Self-Portrait, probably 1626/1641, etching and engraving (etching of head by van Dyck and finished in engraving by J. Neeffs) on laid paper, State vi/vii, Gift of Arthur and Charlotte Vershbow, in Honor of the 50th Anniversary of the National Gallery of Art, 1990.125.1.1

The monotype is perhaps the most experimental and intriguing offshoot of traditional printmaking. Ink is applied to a flat surface (traditionally a copperplate), typically by brushing it on or covering the entire plate and then wiping or daubing it away to create a design. While still damp the plate is run through a press, sometimes yielding two or three impressions. Given the areas of indistinctness this is probably a second (so-called cognate) impression. It is not strictly an unfinished image, but the ghost of a finished one.

Giovanni Benedetto Castiglione, Italian, 1609 or before - 1664, David with the Head of Goliath, c. 1655, monotype in brown oil pigment on laid paper, Andrew W. Mellon Fund, 1977.30.1

The rare, unfinished state of Van Dyck's Self-Portrait is the most prized of all the prints made for a series of portraits of noteworthy figures that came to be called the Iconography. This exquisite rendering set in lofty isolation on the sheet must have been valued not just as an exceptional example of the artist's skill, but also for its haughty abstraction.

Sir Anthony van Dyck, Flemish, 1599 - 1641, Self-Portrait, probably 1626/1641, etching, State i/vii, Rosenwald Collection, 1943.3.8250

Some fifteen years after Van Dyck etched his self-portrait, the engraver Jacob Neeffs completed the plate to serve as the title page for a published edition of the portrait series. The engraved additions complete the bust but rob the image of its spontaneity. Remarkably, Neeffs chose not to remove the accidental scratch across the mustache, implying that even an inadvertent slip of the master's hand merited respect.

Sir Anthony van Dyck, Flemish, 1599 - 1641, and Jacobus Neeffs, Flemish, 1610 - 1660 or after, Self-Portrait, probably 1626/1641, etching and engraving (etching of head by van Dyck and finished in engraving by J. Neeffs) on laid paper, State vi/vii, Gift of Arthur and Charlotte Vershbow, in Honor of the 50th Anniversary of the National Gallery of Art, 1990.125.1.1

Rembrandt

Rembrandt is without doubt the dominant figure in the history of the unfinished print. During the course of his long career he explored the aesthetic question of finish in all its essential dimensions. Among his earliest etchings are the so-called sketch sheets, seemingly random groups of studies often scattered in various orientations on the plate. In other cases he made etchings meant to appear like loosely executed drawings and occasionally left areas uncompleted in largely finished compositions. There is good evidence that most of the examples shown here were printed in the artist's lifetime, implying that he regarded them as worthy of distribution and serious consideration. Although Rembrandt's sometimes brash tendency to experiment is well known, his obsession with the complexities of artistic process and his fascination with exploring the stages of artistic invention are most dramatically revealed in his prints. A later generation attributed to Rembrandt the statement, "a work of art is finished when an artist realizes his intentions." Whether or not he actually said this, it certainly reflects his practice.

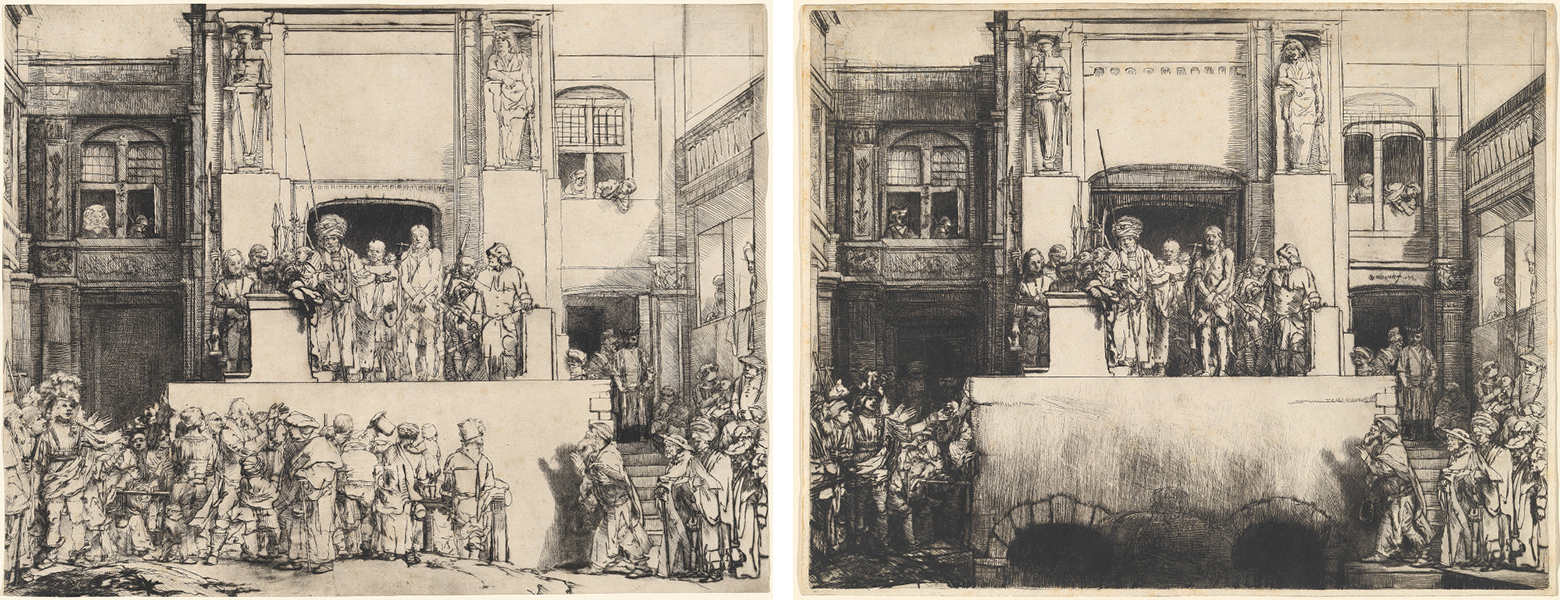

For Rembrandt the revelation of creative process through successive states and differing impressions of a print were fundamental to his understanding of artistic invention. Sequences of states establish a partial record of the artist's thinking and rethinking of an idea (see Christ Presented to the People and The Three Crosses). Like drawings done in preparation for a painting, the evolving states of a print allow us to trace the deliberation that attends the making of any work of art. Yet, unlike drawings, prints record exact stages in reworking the actual image. Over time collectors began to take an interest in this byproduct of the art form, but printmakers were necessarily aware of it from the start. Rembrandt's experiments over the life of a single plate were usually subtle, but sometimes radical. Frequently states in a progression were also independent resolutions.

(left) Rembrandt van Rijn, Dutch, 1606 - 1669, Christ Presented to the People: Oblong Plate, 1655, drypoint, State v/viii, Rosenwald Collection, 1964.8.1863

(right) Rembrandt van Rijn, Dutch, 1606 - 1669, Christ Presented to the People: Oblong Plate, 1655, drypoint, State viii/viii, Rosenwald Collection, 1945.5.109

The landscape with a figure must have been etched first and discarded as unworthy of an independent composition. Then Rembrandt added the fragmentary study for a self-portrait along with a separate trial for the hair or beard (to the right), and the perhaps comic detail of a disembodied eye floating above the beret. This and several other sketch sheets imply that Rembrandt deemed his most incidental studies to have market value.

Rembrandt van Rijn, Dutch, 1606 - 1669, Sheet with Two Studies: a Tree, and the Upper Part of a Head of the Artist Wearing a Velvet Cap, c. 1642, etching, Rosenwald Collection, 1943.3.7202

Rembrandt never signed or dated this etching. Is it truly unfinished, or only unfinished in a conventional sense? The summary indications of pose and background make clear that the artist foresaw a more complete image. However, the intense focus of the figure and its firm positioning suggest that Rembrandt may have stopped short because he had accomplished the essential in what he set out to do. The unfinished areas amplify the effect of the light that motivates the old man's gesture. Rembrandt was preoccupied with vision and blindness, which suggests that here, too, he may have intended us to reflect on the nature and vulnerability of sight.

Rembrandt van Rijn, Dutch, 1606 - 1669, Old Man Shading His Eyes with His Hand, c. 1639, etching and drypoint on laid paper, New Century Fund, 1998.25.1

This early etching encapsulates the full significance of the unfinished print for Rembrandt. Less than half completed, the major parts of the composition are set down only in drypoint. The figure of the artist shown drawing in his workshop gives every indication of being a self-portrait, and his model (and muse) surely alludes to Venus. Behind them are a large canvas on an easel, a sculpted bust, and other studio props. The image is manifestly an allegory of art. It celebrates the act of rendering, the importance of truth to nature, and the classical tradition, all paradoxically declared in the unfinished portion of the print. Given the subject and its incomplete state, this print must have been understood as a performance in fine draftsmanship and etching technique, but most of all as an unveiling of Rembrandt's creative process.

Rembrandt van Rijn, Dutch, 1606 - 1669, The Artist Drawing from the Model, c. 1639, etching, drypoint and burin, State ii/ii, Print Purchase Fund (Rosenwald Collection), 1968.4.1

This plate yielded one of Rembrandt's most prized sequences of states. The early steps show only minor alterations. Before a stagelike proscenium a motley rabble confronts the lonely figure of Christ, mocking him with gestures all the more sinister for being offhanded and mundane. Brute passages of drypoint delineate the figures in the crowd with a remarkable bluntness, ranking them among the finest examples of draftsmanship anywhere in Rembrandt's art.

Rembrandt van Rijn, Dutch, 1606 - 1669, Christ Presented to the People: Oblong Plate, 1655, drypoint, State v/viii, Rosenwald Collection, 1964.8.1863

Rembrandt's decision to rub out (burnish) the foreground in the final state of the plate comes as a shock. Whether this was occasioned by damage to the plate or a dramatic shift in his interpretation of the event remains a mystery, all the more so because of the strange apparition set in place of the people. Rembrandt's transformation is most dramatic below the proscenium where a ghostly giant appears framed by the arches of a crypt. As if to signal the elevation of human tragedy to a portent of epic disaster, the face of Hercules lodged in the right-hand niche above the entryway has been scarred into the aspect of a monster. Only in this last, sullied conception did Rembrandt sign and thereby authorize the print for a commercial edition, even though the entire center-foreground is defiled by incomplete burnishing.

Rembrandt van Rijn, Dutch, 1606 - 1669, Christ Presented to the People: Oblong Plate, 1655, drypoint, State viii/viii, Rosenwald Collection, 1945.5.109

The first two states of this plate evolve with subtle revisions. This impression of the first state is printed on vellum, a support that repels ink rather than absorbs it, causing the lines to blur into an indistinct fog that amplifies the penumbral gloom enveloping the scene.

Rembrandt van Rijn, Dutch, 1606 - 1669, Christ Crucified between the Two Thieves (The Three Crosses), 1653, drypoint and burin, State i/v, Gift of R. Horace Gallatin, 1949.1.50

In the third state conspicuous changes appear across the left and right foreground, although an impression on paper registers so differently that they are difficult to discern. At this point Rembrandt signed and dated the plate, printing it in significant number on different types of paper and often with distinctly different wipings to vary the tone.

Rembrandt van Rijn, Dutch, 1606 - 1669, Christ Crucified between the Two Thieves (The Three Crosses), 1653, drypoint and burin, State iii/v, Rosenwald Collection, 1943.3.9115

Here Rembrandt transformed his original conception into something utterly haunting. Large areas are savagely scored out in drypoint and engraving. Christ's face is slightly lifted, as if to revive him in the moment of epiphany. John the Evangelist (to the right) raises his hands aloft, and the converted centurion kneeling before the cross bows his head. An equestrian figure in exotic headgear, almost certainly Pilate, looms ominously in the half-light supplanting the earlier group to the left. The condemned thief at right is completely shrouded by night. It is the ninth hour, and with the shuddering of an earthquake a pall of darkness has descended over the land. In effect the fourth state is an entirely different work forged on the same plate, as if Rembrandt had to deface and reform the matrix of the copper in order to revolutionize his initial idea.

Rembrandt van Rijn, Dutch, 1606 - 1669, Christ Crucified between the Two Thieves (The Three Crosses), 1653, drypoint and engraving on laid paper, State iv/v, Rosenwald Collection, 1943.3.7174

French Rococo Etched Proofs

In France, the academic stronghold of classical art theory in the eighteenth century, prints gained wider acceptance as objects suitable for domestic display. By this time prints were regularly made to reproduce paintings. The resulting subordination of the print put a premium on capturing the pictorial values of a painting and set the question of finish on a different plane. The exclusive use of etching for the first stage in making these reproductive prints reflects an appreciation for the particular delicacy and virtuosity afforded by the technique. Once the initial design was complete the plate was then typically reworked with an engraving tool to enrich the detail and shading. The overriding importance of the preliminary etched work is apparent from the fact that the artists enlisted at this crucial phase were chosen for their facility. The association of etching with freedom of draftsmanship had long been acknowledged in writings on prints. Consequently, the etched proofs were regularly printed in significant number and apparently disseminated and collected by discriminating connoisseurs. In the following century the taste for etched-only proofs reached a highpoint.

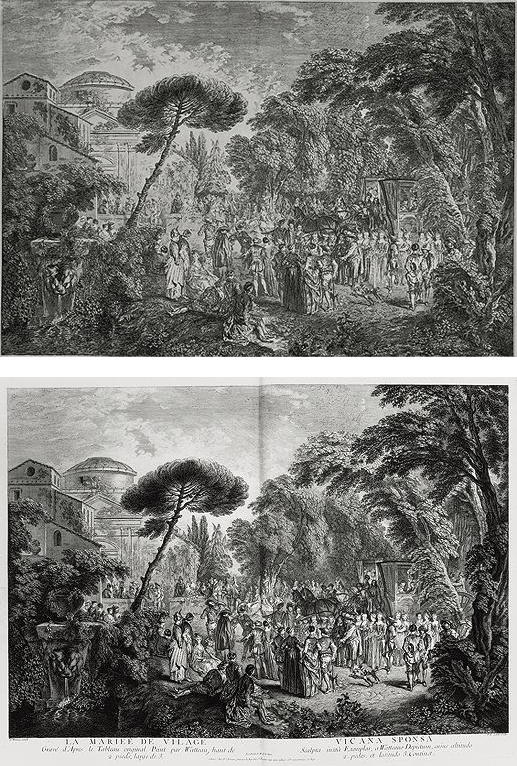

(left) Charles-Nicolas Cochin I after Antoine Watteau, French, 1688 - 1754, La Mariee de Village (The Village Bride), 1729, etching, Andrew W. Mellon Fund, 1978.25.3

(right) Charles-Nicolas Cochin I, French, 1688-1754, La Mariée de Village (The Village Bride) (Antoine Watteau), 1729, from L'oeuvre d'Antoine Watteau, compiled by Jean de Julienne c. 1740 with engravings by various artists, Widener Collection, 1942.9.2092

The proof conveys all the essential elements of the image with an ethereal refinement characteristic of French rococo art. The lightness of the etched lines retains the spontaneity of the artist's initial design on the plate.

Charles-Nicolas Cochin I after Antoine Watteau, French, 1688 - 1754, La Mariee de Village (The Village Bride), 1729, etching, Andrew W. Mellon Fund, 1978.25.3

For the final state of this print the plate was reworked with engraving, deepening the shadows, strengthening the modeling of the figures, and giving more substance and dimension to the landscape. These subtle but consequential steps transform what was innately a print into the imitation of a painting.

Charles-Nicolas Cochin I, French, 1688-1754, La Mariée de Village (The Village Bride) (Antoine Watteau), 1729, from L'oeuvre d'Antoine Watteau, compiled by Jean de Julienne c. 1740 with engravings by various artists, Widener Collection, 1942.9.2092

Piranesi and the Invented Fragment

Giovanni Battista Piranesi's beguiling archaeological phantasms form a striking contrast to the dream world of French rococo prints. Piranesi is best known for reimagining the world of antiquity from the eloquence of its ruins, degraded remnants that became a model for creating fragmented scenarios of his own invention. A generation later the critic Friedrich Schlegel observed: "Many works of the ancients have become fragments. Many modern works are fragments at the moment of their inception." Schlegel deemed every work of art the fragment of a greater whole, something that could only be realized by a leap of the spirit into the sublime. Thus, for romantic theorists the invented fragment or the artificially contrived ruin both embodied and expressed the extreme subjectivity of all aesthetic experience. The idea that a work of art could never be complete in itself was radical, and for Piranesi the subject of the ruin is often inseparable from the manner of its rendering.

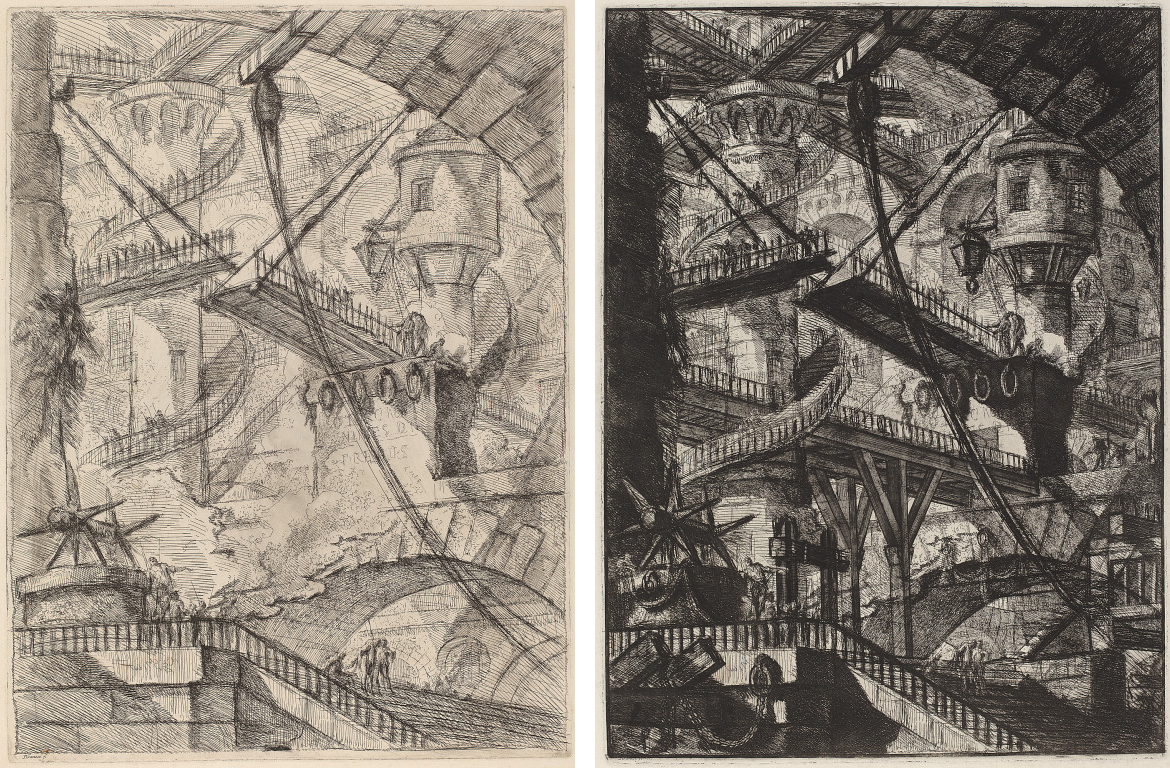

(left) Giovanni Battista Piranesi, Italian, 1720 - 1778, The Drawbridge, published 1749/1750, etching, engraving, scratching, State i/vi, W.G. Russell Allen, Ailsa Mellon Bruce, Lessing J. Rosenwald, and Pepita Milmore Funds, 1976.35.5

(right) Giovanni Battista Piranesi, Italian, 1720 - 1778, The Drawbridge, published 1780s, etching, engraving, scratching, State v/vi, Rosenwald Collection, 1943.3.6992

The interiors and semi-interiors of the Carceri are often paradoxical: domineering and ephemeral, oppressive and yet open to light and atmosphere, at once fanciful arenas for careful exploration and spatial conundrums impossible to navigate.

Giovanni Battista Piranesi, Italian, 1720 - 1778, The Drawbridge, published 1749/1750, etching, engraving, scratching, State i/vi, W.G. Russell Allen, Ailsa Mellon Bruce, Lessing J. Rosenwald, and Pepita Milmore Funds, 1976.35.5

The changes in the later states are usually interpreted as enhancing a sense of disorientation and existential malaise. However, a more detached analysis suggests that Piranesi shored up and clarified his initial conception, investing his imaginings with gravity and permanence where instability and caprice once reigned.

Giovanni Battista Piranesi, Italian, 1720 - 1778, The Drawbridge, published 1780s, etching, engraving, scratching, State v/vi, Rosenwald Collection, 1943.3.6992

Nineteenth-Century Paris

During the nineteenth century etching was revitalized, once again stressing its originality and immediacy as an art form. Rembrandt cast an imposing shadow over this development. However, the retrospective tendency of the etching revival was inflected by newly romantic conceptions of nature and the self. In 1862, the poet and critic Charles Baudelaire declared etching to be "a genre so personal...it would be difficult for the artist not to describe on the plate his most intimate personality." Meanwhile, the invention of lithography and photography, alongside various industrial and scientific advances, renewed the printmakers' longstanding infatuation with technical process. A culture now more attuned to technology affected them in contradictory ways. The advantages offered by new means of mass reproduction were seen by many artists as a threat to their individuality. Therefore printmakers began to experiment in ways that subverted the uniformity characteristic of the medium.

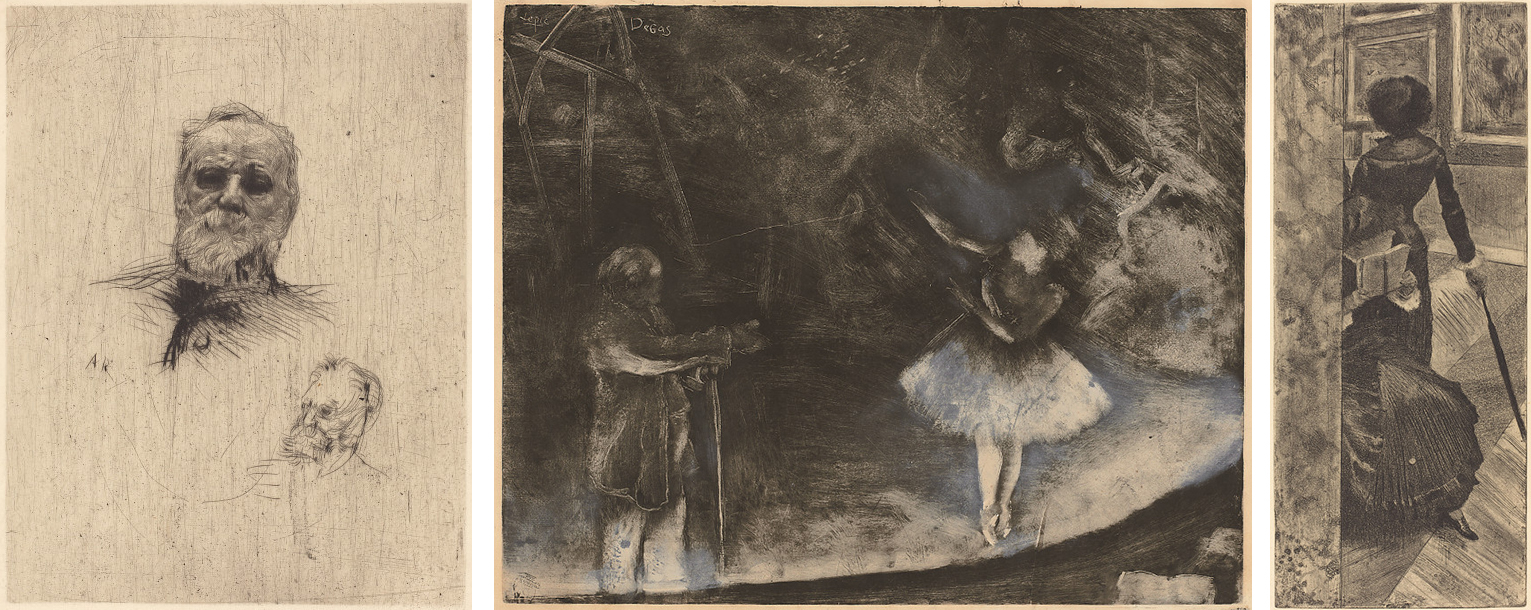

(left) Auguste Rodin, French, 1840 - 1917, Victor Hugo, De Face, 1886, drypoint, State iii/vii, Rosenwald Collection, 1943.3.7406

(middle) Edgar Degas, French, 1834 - 1917, executed in collaboration with Vicomte Ludovic Napoléon Lepic, French, 1839 - 1889, The Ballet Master (Le maître de ballet), c. 1874, monotype heightened and corrected with white chalk or wash, Rosenwald Collection, 1964.8.1782

(right) Edgar Degas, French, 1834 - 1917, Mary Cassatt at the Louvre: The Paintings Gallery (Au Louvre: La Peinture), c. 1879/1880, etching, aquatint, drypoint, and electric crayon on wove paper, State xviii/xx, Rosenwald Collection, 1946.21.106

Edgar Degas

Through a complex sequence of copies, tracings, and reversals, Degas generated at least three compositions on the basis of the two figures in the images above. Each print went through several states. Degas seems to have considered every phase important in itself and probably exhibited the prints as discrete works of art as well as progress proofs. The print on the far right derives from the two on the left. Degas retraced the drawing, reversed one figure, and overlapped it with the other to construct an entirely new composition.

(left) Mary Cassatt at the Louvre: The Etruscan Gallery (Au Louvre: Musée des antiques), 1879/1880, etching and drypoint in black on laid paper, State i/vi, Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Paul Mellon, 1995.47.73

(middle) Mary Cassatt at the Louvre: The Etruscan Gallery (Au Louvre: Musée des antiques), c. 1879/1880, etching, aquatint, and electric crayon, State vi/vi, Rosenwald Collection, 1943.3.3366

(right) Mary Cassatt at the Louvre: The Paintings Gallery (Au Louvre: La Peinture), c. 1879/1880, etching, aquatint, drypoint, and electric crayon on wove paper, State xviii/xx, Rosenwald Collection, 1946.21.106

"Unfinished" portraits having the look of a proof state became a "finished" genre in its own right, evoking the preliminary pencil sketch made in a private sitting. Rembrandt’s example was a necessary if not sufficient condition for promoting this fashion.

Auguste Rodin, French, 1840 - 1917, Victor Hugo, De Face, 1886, drypoint, State iii/vii, Rosenwald Collection, 1943.3.7406

Lepic introduced Degas to monotype printing. Here the ink was spread over the entire surface of the plate and worked with a pointed instrument and pieces of cloth before printing. Although both artists' signatures appear on the image, Lepic probably only instructed Degas in making the print. Working in the negative and tolerating accident seems to have liberated Degas from the precise, deliberate style of drawing he was accustomed to. The monotype was usually a provisional step that served as an impulsive starting point. Once the plate was printed he often worked over his monotypes with pastel.

Edgar Degas, French, 1834 - 1917, executed in collaboration with Vicomte Ludovic Napoléon Lepic, French, 1839 - 1889, The Ballet Master (Le maître de ballet), c. 1874, monotype heightened and corrected with white chalk or wash, Rosenwald Collection, 1964.8.1782

Modernity

By the turn of the twentieth century the problem of the unfinished print had been taken to its furthest reaches--the possibility of a work of art in a perpetual state of becoming. All barriers had been effectively breached and the matter of unfinish transformed from a practical and philosophical problem to a precondition of modernity. In certain conspicuous instances the question of finish could be indefinitely suspended. Alternately accepting and rejecting the implications of its technological foundation, the print had its own contribution to make to modernist aesthetics. The provisional nature of the unfinished "state" presupposing some final version had by this time been well authorized as a work of art worthy of exhibiting and collecting in its own right. Hence, the dictum attributed to Rembrandt that a work of art is finished whenever its maker determines it to be was superseded by a wider claim to subjectivity, extending the prerogative to include the beholder as well. "When is it complete and when is it not complete? I don't think one can say what one longs for" (Jasper Johns, 1981).

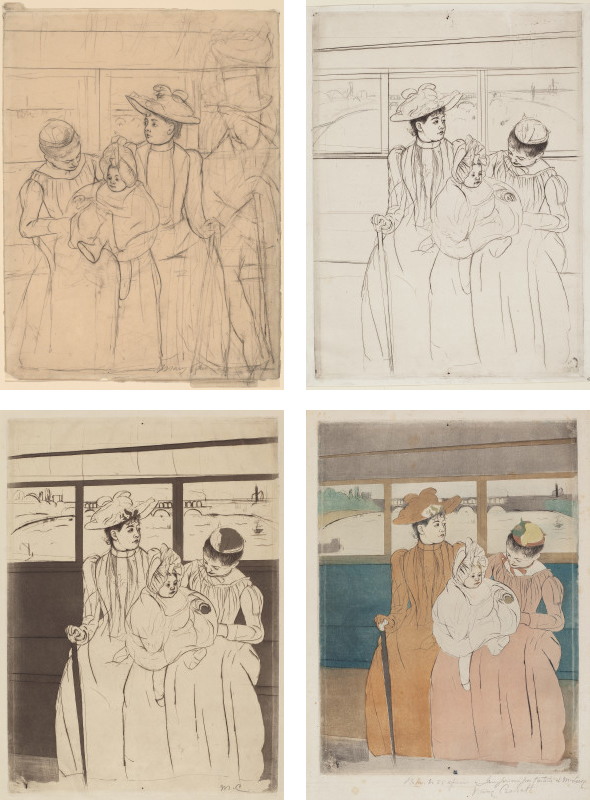

Mary Cassatt

Mary Cassatt, who spent the better part of her career in Paris, was an important innovator in color printing as well as in her subject matter. This sequence demonstrates her approach to making a color etching, beginning with a drawing and proceeding through successive states to the final stage when the plate was published as an edition. Cassatt was one of the first artists to exhibit proof states as self-sufficient works and a demonstration of process.

(top left) In the Omnibus [recto], c. 1891, black chalk and graphite on wove paper, Rosenwald Collection, 1948.11.51.a

(top right) In the Omnibus, c. 1891, soft-ground etching and drypoint in black, reworked with graphite, State ii/vii, Rosenwald Collection, 1946.21.93

(bottom left) In the Omnibus, c. 1891, soft-ground etching, drypoint, and aquatint in black, State iv/vii, Rosenwald Collection, 1943.3.2752

(bottom right) In the Omnibus, 1890-1891, drypoint and aquatint on laid paper, State vii/vii, Chester Dale Collection, 1963.10.250

Villon--La Parisienne

Jacques Villon's ten variant proofs of La Parisienne deviate from the norms of printmaking: there is no definitive state, no known final edition, and no apparent attempt to create uniformity. Instead the artist was absorbed in varying color and impression. The sequence begins with the impression in black (proof 1). Villon went on to introduce additional plates and colors. In the third proof he included color notes as a guide for the printer. In the fifth he cropped about an inch from the plates at bottom and left; and in the ninth he heavily burnished out most of the background, severely reducing the ornateness of the interior and edging the image toward abstractness. Villon's experiments with La Parisienne chronicle his artistic development into relative abstraction. At the turn of the century, the condition of "unfinish" had become an essential aspect of modernist thinking.

On the basis of the Gallery's proof impressions, and extrapolating to other extant proofs, the case can be made that Villon's development of the print was undertaken in three distinct campaigns. The first comprised the initial working of the plate(s) and elaboration of the ornate setting, the "additive" phase of the print's evolution (proofs 1-4). The artist's cropping of the plates signals the second campaign, which took a "subtractive" course toward simplicity and the beginnings of abstraction (proofs 5-9). The third and last campaign included both additive and subtractive changes, which further extended the work's shift toward abstraction (proof 10).

(top row, left to right)

Proof 1. La Parisienne (2), 1902, softground etching, etching, and aquatint in black printed from one plate on beige wove paper, Eugene L. and Marie-Louise Garbaty Fund, 1999.93.1

Proof 2. La Parisienne (4), 1902, color softground etching, etching, and aquatint printed from multiple plates on cream wove paper, Edward E. MacCrone Fund, 1999.93.2

Proof 3. La Parisienne (7), 1902, color softground etching, etching, and aquatint printed from multiple plates with watercolor additions and graphite notations on cream wove paper, Ailsa Mellon Bruce Fund, 1979.17.1

Proof 4. La Parisienne (8), 1902, color softground etching, drypoint, etching, aquatint, and embossing (in white) printed from multiple plates on cream laid paper, Gift of Philip and Judith Benedict, 1997.88.1

Proof 5. La Parisienne (10), 1902, color softground etching, drypoint, etching, aquatint, and embossing (in white) printed from multiple plates on white wove paper, New Century Fund, 1999.54.1

(bottom row, left to right)

Proof 6. La Parisienne (11), 1902, color softground etching, drypoint, etching, aquatint, and embossing (in pinkish white) printed from multiple plates on cream wove paper, Gift of Evelyn Stefansson Nef, 1999.53.1

Proof 7. La Parisienne (13), 1902, color softground etching, drypoint, etching, aquatint, and embossing (in brown) printed from multiple plates on white wove paper, New Century Fund, 1999.54.2

Proof 8. La Parisienne (12), 1902, color softground etching, drypoint, etching, aquatint, and embossing (in black) printed from multiple plates on cream wove paper, New Century Fund, 1999.54.3

Proof 9. La Parisienne (15), 1902, color drypoint, etching, aquatint, burnishing, and inkless embossing printed from multiple plates on cream wove paper, New Century Fund, 1999.54.4

Proof 10. La Parisienne (18), 1903, color drypoint, etching, and aquatint with scraping and burnishing printed from multiple plates on cream wove paper, New Century Fund, 1999.54.5

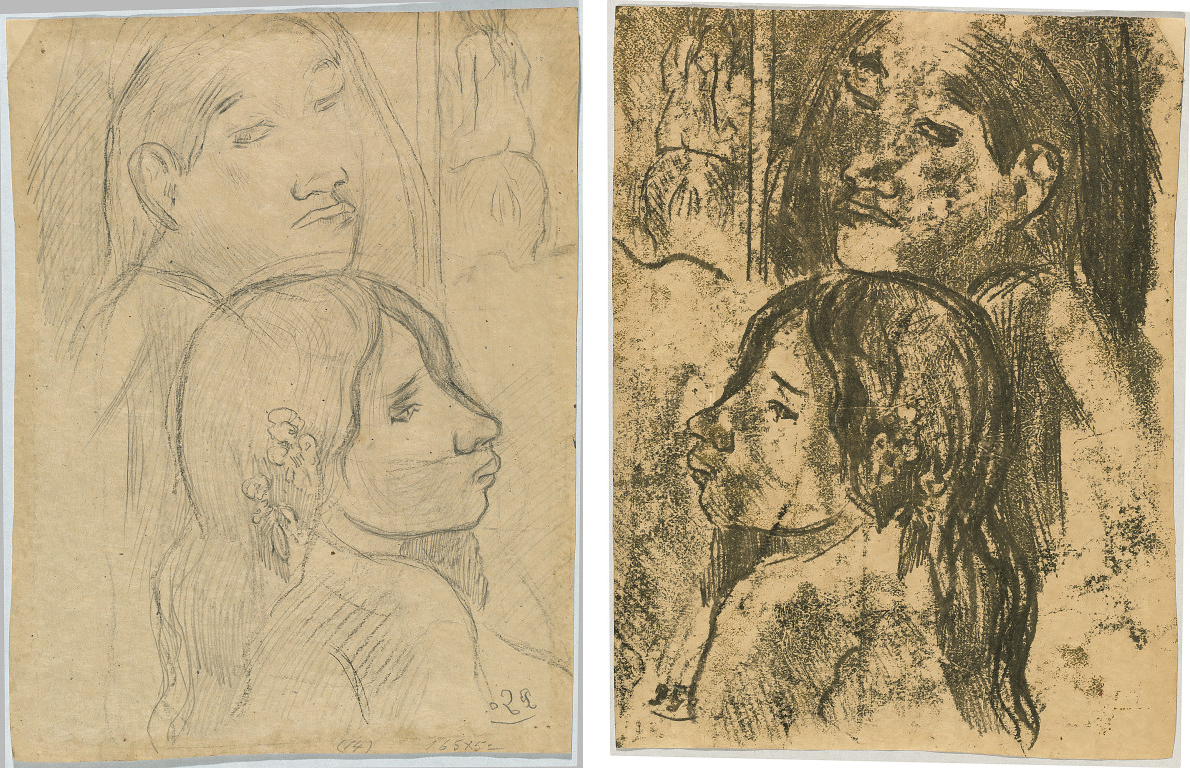

Gauguin

This monotype comes from Gauguin's Tahitian period and was created in ways that are both direct and complex. Partly because of his geographical isolation Gauguin worked with relatively simple materials. His techniques permitted a considerable tolerance of accident, causing irregularly textured patterns, broken lines, and intermittent blotches on the images. Hence this print falls distantly into the tradition of the constructed fragment, an initially romantic idea transformed into a consciously "primitivist" aesthetic.

It appears from Gauguin's own description that he began the monotype on the front of this sheet (right) by making the drawing on its back (left). He applied printer's ink or watercolor to a second sheet and laid his drawing on top of it face up. He then traced over the drawing so the pressure of his instruments caused the pigment on the underlying sheet to transfer to the reverse of the drawing. Gauguin's procedure for creating this monotype evokes the fragmentary effect of a degraded drawing.

(left) Two Marquesans [verso], c. 1902, pencil and crayon, Rosenwald Collection, 1964.8.1797.b

(right) Two Marquesans [recto], c. 1902, traced monotype in warm black retouched slightly with an olive pigment, Rosenwald Collection 1964.8.1797.a