Rembrandt van Rijn: Abraham Entertaining the Angels

Introduction

Rembrandt van Rijn brought a powerful intellect and astute psychological insight to his interpretations of biblical events.

Over the course of his career Rembrandt made about three hundred etchings. With many impressions of each image, his prints were seen by artists and collectors throughout Europe and brought the artist international fame.

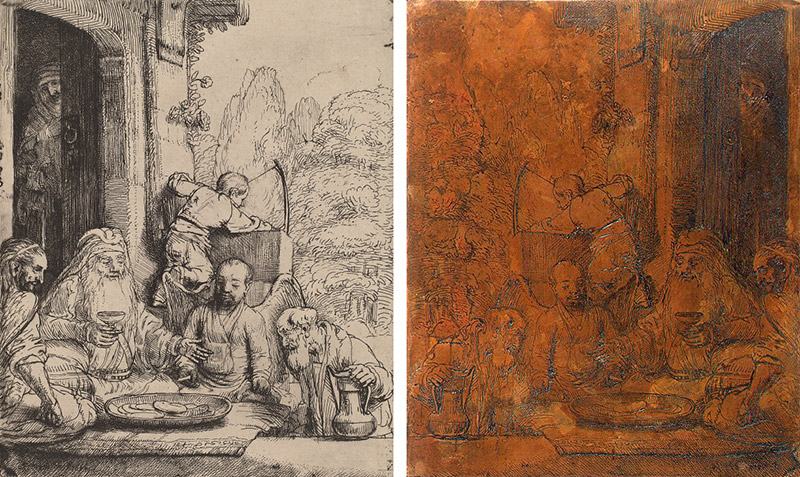

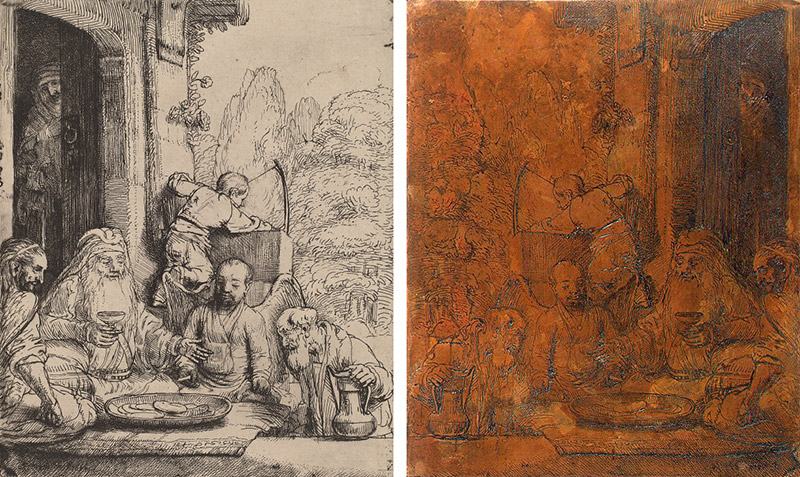

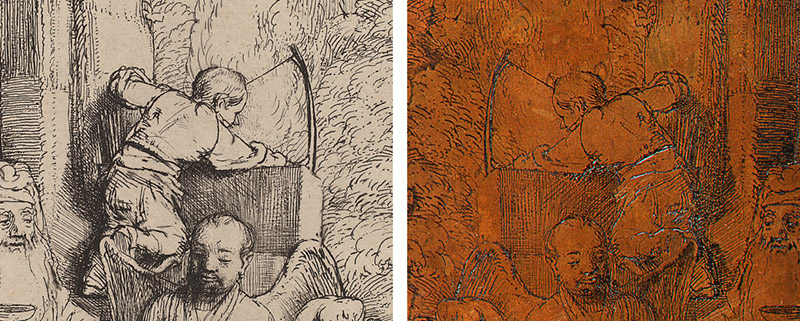

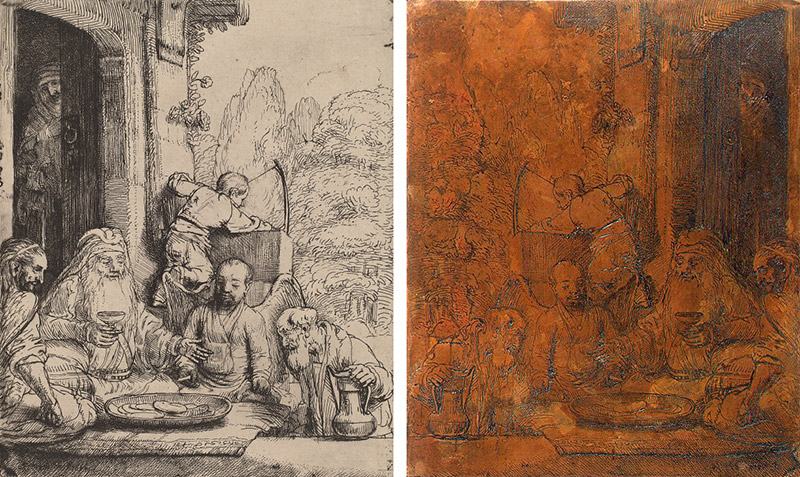

(left) Abraham Entertaining the Angels, 1656, etching and drypoint, Rosenwald Collection, 1943.3.7160

(right) Abraham Entertaining the Angels [recto], 1656, etched copperplate with drypoint, Gift of Ladislaus and Beatrix von Hoffmann and Patrons' Permanent Fund, 1997.85.1.a

The Story

The subject of this print, Abraham Entertaining the Angels, comes from the Old Testament (Genesis 18:1-15). For years, Abraham and his wife Sarah had longed for children. One hot day three travelers appeared at Abraham's house, and he invited them to rest and eat. The visitors were actually angels and God himself, who announced that Sarah would have a son within the year. Rembrandt depicts the dramatic moment in the story when the miracle is revealed through the gesture of the figure in the center, representing God.

Abraham Entertaining the Angels, 1656, etching and drypoint, Rosenwald Collection, 1943.3.7160

Rembrandt followed an unusual interpretation that appeared in the Dutch States Bible of 1637: rather than depicting three similar angels, each is unique. God is represented as a large, bearded man. He is given center stage as the dominant figure who has come to speak directly to Abraham.

The distinctive facial features and arrangement of the angels—seated in a semicircle on the ground before a platter of food—are adapted from a Moghul miniature painting in Rembrandt's own collection. He often sought out Middle Eastern sources and motifs to make biblical images historically resonant.

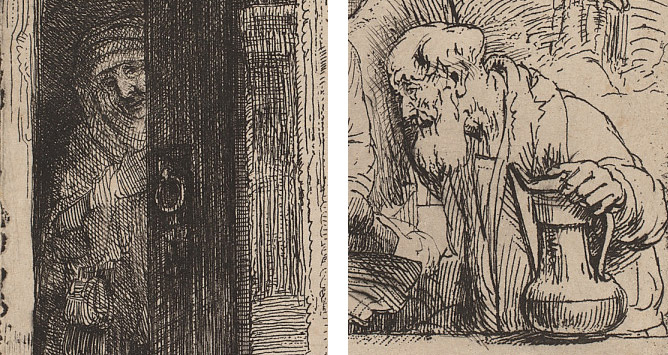

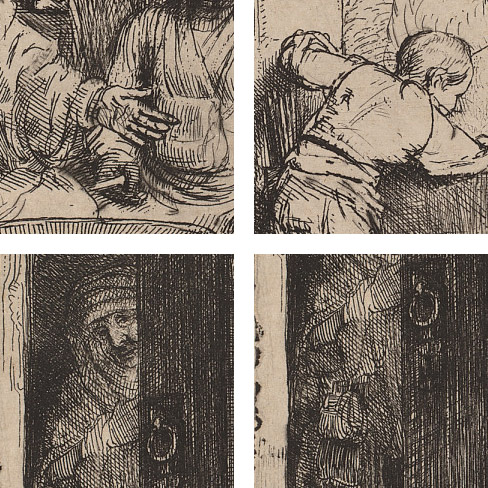

Abraham Entertaining the Angels (detail), 1656, etching and drypoint, Rosenwald Collection, 1943.3.7160

For years God had promised Abraham and Sarah a child—in fact, their offspring were to be "as numerous as the stars in heaven." But now, Abraham is ninety-nine years old and Sarah only ten years younger, long past hoping for a child.

When Sarah hears God's amazing announcement, she laughs to herself in disbelief. Rembrandt emphasizes her age and places her in the dark, shadowed doorway to signify her doubt and lack of faith.

Abraham, in contrast, responds as a humble servant: he bows his head in acceptance. In the Book of Genesis, the story of Abraham is about faith. God tests him repeatedly, yet Abraham remains faithful.

Sarah and Abraham are psychologically real. We sense their individual personalities—Sarah a skeptic; Abraham constant in his faith.

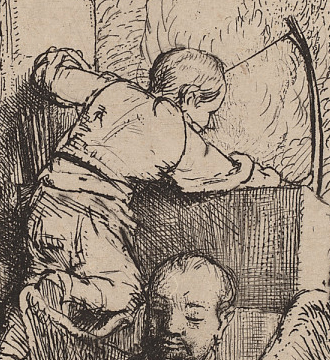

(top) Abraham Entertaining the Angels (detail), 1656, etching and drypoint, Rosenwald Collection, 1943.3.7160

(bottom) Abraham Entertaining the Angels (detail), 1656, etching and drypoint, Rosenwald Collection, 1943.3.7160

Rembrandt, like many visual artists, chose a single moment to represent the entire narrative, but he often enriched his images with references to other episodes in a story.

Ishmael, the young boy in the center of the composition, plays this role. When Sarah failed to bear a child earlier in their lives, she urged Abraham to take her servant, Hagar, to produce an heir. Hagar gave birth to Ishmael.

Abraham Entertaining the Angels (detail), 1656, etching and drypoint, Rosenwald Collection, 1943.3.7160

Ishmael takes a prominent place in the composition; he is in the center where, following scripture, normally a tree would have been. Why did Rembrandt choose to give Ishmael such prominence? Ishmael symbolizes doubt—he was the result of Sarah's loss of faith in God's promise of her own child.

In this image Rembrandt emphasizes the meaning of the story rather than simply depicting narrative detail. The skepticism of Sarah and the estrangement of Hagar's son Ishmael, one in the shadow, the other turned away from the central event, heighten the drama of Abraham's affirmation of faith, his covenant with his Divine visitor.

Abraham Entertaining the Angels, 1656, etching and drypoint, Rosenwald Collection, 1943.3.7160

The promise God made to Abraham and Sarah that day was indeed fulfilled. Sarah gave birth to a son, Isaac. These images tell more about their story.

(left) Abraham Casting Out Hagar and Ishmael, 1637, etching with touches of drypoint, Rosenwald Collection, 1943.3.7237

(middle) Abraham and Isaac, 1645, etching and burin, Rosenwald Collection, 1963.11.179

(right) Abraham's Sacrifice, 1655, etching and drypoint, Rosenwald Collection, 1943.3.7161

Although Sarah had urged Abraham to have a child with her servant Hagar, she became jealous when Isaac was born, demanding that Abraham banish Hagar and Ishmael. God told Abraham to obey.

Rembrandt places Abraham between Sarah, seen behind him in the window, and Hagar, who is departing in tears. One foot on the steps of his house, the other on the path, Abraham's inner conflict is made clear. His gesture—blessing Ishmael—expresses his reluctance and sadness. He does not wish to lose his first son. Yet in obedience to God, Abraham steps back toward his house, where little Isaac waits in the doorway.

Abraham Casting Out Hagar and Ishmael, 1637, etching with touches of drypoint, Rosenwald Collection, 1943.3.7237

In the later part of his career Rembrandt often focused on scenes of quiet personal drama, as in this touching image of Abraham and Isaac. The story tells of God testing Abraham by commanding him to sacrifice Isaac. "He said to him, 'Abraham!...Take your son, your only son Isaac, whom you love...and offer him...as a burnt offering."

In this print, Rembrandt portrays the moment when Isaac, unaware of his fate, asks innocently, "Father! The fire and the wood are here, but where is the lamb for a burnt offering?" Abraham gestures toward heaven: "God himself will provide a lamb for the burnt offering, my son."

Abraham and Isaac, 1645, etching and burin, Rosenwald Collection, 1963.11.179

Rembrandt captures the emotion of this intimate encounter between father and son: Abraham's face is sad but stern, expressing both love for his child and obedience to God. Isaac trusts his father completely.

Abraham and Isaac (detail), 1645, etching and burin, Rosenwald Collection, 1963.11.179

Here Rembrandt portrays the moment in the story when Abraham has raised the knife to sacrifice Isaac. An angel suddenly appears, calling, "Abraham! Abraham! Do not lay your hand on the boy or do anything to him; for now I know that you fear God."

In Rembrandt's work, the angel does not call to Abraham but swoops down in a stream of light and embraces him, seizing his arms to prevent him from killing his son. Many interpretations emphasize Isaac's terror. But Rembrandt focuses on Abraham, whose hand covers Isaac's eyes protectively, a tender gesture toward the son he has prepared to sacrifice. Abraham's eyes, pools of black, suggest blindness—his unwavering, blind faith in God.

Abraham's Sacrifice, 1655, etching and drypoint, Rosenwald Collection, 1943.3.7161

Techniques

By temperament, Rembrandt was a born etcher. The etching process requires manual skill, an understanding of chemistry, the desire to experiment, and artistic vision, all of which Rembrandt had in abundance. Whether painting or making prints, his work blended aesthetic and technical innovation with exceptional insight into the human spirit. The etching medium permitted him to experiment and to create the expressive lines and rich tonal effects he sought.

(left) Abraham Entertaining the Angels, 1656, etching and drypoint, Rosenwald Collection, 1943.3.7160

(right) Abraham Entertaining the Angels [recto], 1656, etched copperplate with drypoint, Gift of Ladislaus and Beatrix von Hoffmann and Patrons' Permanent Fund, 1997.85.1.a

In this self-portrait, made in 1648, the angle of the drawing board and the tool in his hand indicate that Rembrandt is probably etching.

Self-Portrait Drawing at a Window, 1648, etching, drypoint, and burin, Rosenwald Collection, 1943.3.7134

Rembrandt's prints are mainly etchings, at times combined with other techniques. In the seventeenth century, engraving was a widely used graphic technique that was popular for many types of images.

To make an engraving, the artist carves a design directly into a metal plate using a pointed tool called a burin, which produces deep, precise lines. The plate is hard, and cutting into the surface requires exact control. Cornelisz. Visscher's Large Cat displays the sharply defined, uniform lines typical of engraving. Engraving was often used for books and maps because of its precision and because many copies could be made from a single plate.

Cornelis Visscher, Dutch, 1629 - 1662, The Large Cat, c. 1657, engraving on laid paper, Ailsa Mellon Bruce Fund, 1995.72.1

The technique of woodcut, seen here in an example by the artist Lucas van Leyden, was practiced and perfected in earlier centuries. Woodcut is a relief process in which the printmaker carves away wood to create raised lines. When inked and pressed against a sheet of paper, the lines form the image. The background areas, being carved out, remain blank.

Lucas van Leyden, Netherlandish, 1489/1494 - 1533, The Poet Virgil Suspended in a Basket, c. 1512, woodcut, Gift of W.G. Russell Allen, 1941.1.170

Rembrandt preferred etching because it allowed him greater freedom. He could achieve rich effects of light and dark and easily draw varied, expressive lines.

To make an etching, an artist uses a copperplate. The image shown on this page represents the actual plate Rembrandt used to make Abraham Entertaining the Angels. First, he covered it with a soft, acid-resistant "ground." Rembrandt invented his own two-part mixture: a black resin covered with a white paste.

Abraham Entertaining the Angels [recto], 1656, etched copperplate with drypoint, Gift of Ladislaus and Beatrix von Hoffmann and Patrons' Permanent Fund, 1997.85.1.a

To create the image, Rembrandt incised, or drew on, the ground with an etching needle. Since the ground was soft, he could draw easily, almost as if he were using a pencil.

Abraham Entertaining the Angels [recto] (detail), 1656, etched copperplate with drypoint, Gift of Ladislaus and Beatrix von Hoffmann and Patrons' Permanent Fund, 1997.85.1.a

Once the design was complete, the plate was immersed in acid, a process called "biting." The acid would eat away the copper along the exposed lines without affecting the resin-covered areas. The acid-bitten lines of an etching are more ragged and less even than engraved lines.

Abraham Entertaining the Angels [recto] (detail), 1656, etched copperplate with drypoint, Gift of Ladislaus and Beatrix von Hoffmann and Patrons' Permanent Fund, 1997.85.1.a

After the biting process, Rembrandt (or one of his assistants) would have scraped away the remaining resin, covered the plate with ink, and then wiped it clean so that ink remained only in the incised, or etched, lines. You can see some ink still embedded in Rembrandt's copperplate.

The print itself was made by placing a piece of paper on top of the plate and rolling the plate and paper through a press. The pressure of the press forced the ink onto the paper, producing the image.

Abraham Entertaining the Angels [recto] (detail), 1656, etched copperplate with drypoint, Gift of Ladislaus and Beatrix von Hoffmann and Patrons' Permanent Fund, 1997.85.1.a

At this stage, Rembrandt could repeat the printing process. Often, however, he added to the image, using a technique called drypoint: drawing with the etching needle directly into the plate. Drypoint leaves a small amount of rough metal residue, or burr, along each line. This residue, no longer visible on the plate, catches the ink and creates a variable, deep, soft line on the print.

(left) Abraham Entertaining the Angels (detail), 1656, etching and drypoint, Rosenwald Collection, 1943.3.7160

(right) Abraham Entertaining the Angels [recto] (detail), 1656, etched copperplate with drypoint, Gift of Ladislaus and Beatrix von Hoffmann and Patrons' Permanent Fund, 1997.85.1.a

In Abraham Entertaining the Angels, Rembrandt enhanced certain areas using drypoint: for example, the outline around God's gesturing hand, the deep shadow along Ishmael's back, and the deeply incised, dark shadows surrounding Sarah. The lighter lines that make up Sarah's dress were probably etched.

Rembrandt frequently combined etching and drypoint, but he also used the burin—the engraving tool—on occasion, when he wished to achieve a more regular line.

Abraham Entertaining the Angels (details), 1656, etching and drypoint, Rosenwald Collection, 1943.3.7160

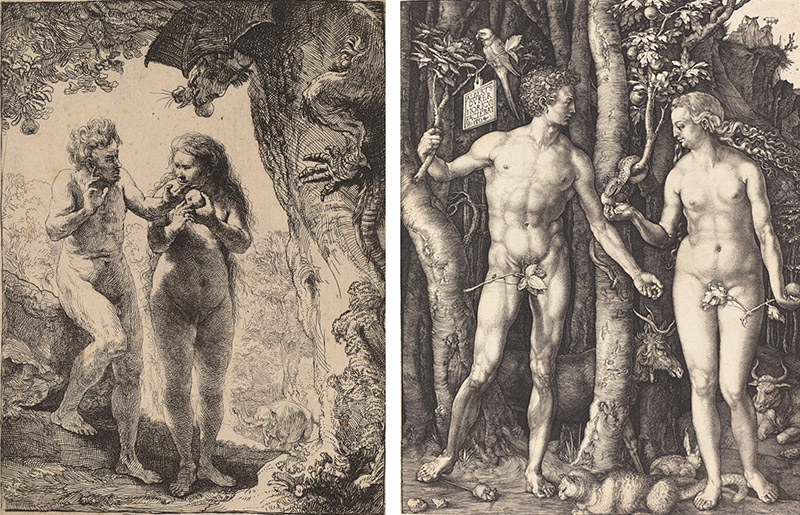

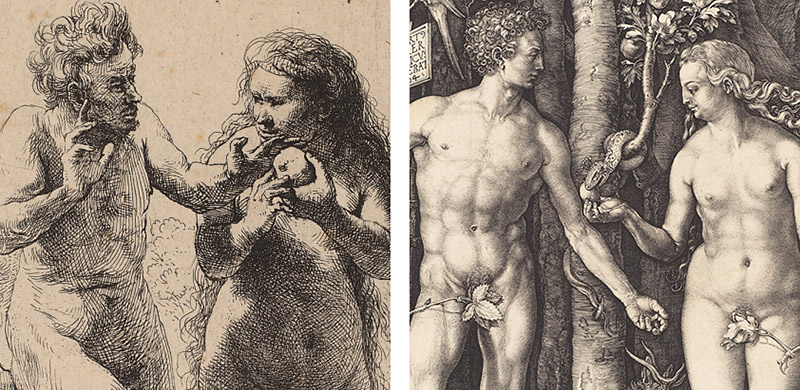

Expressive, rapidly drawn, rich and varied lines are characteristic of Rembrandt's etching style. A comparison between Rembrandt's etched Adam and Eve and Albrecht Dürer's engraved version of the same subject reveals some of the differences in these printmaking techniques.

Like Rembrandt, the German artist Albrecht Dürer was a brilliant printmaker. He presents Adam and Eve as clearly drawn, well-modeled figures against a curtain of trees, an arcadian wooded setting. The clean, precise lines of this engraving, made in 1504, perfectly suit the classical ideals of the Renaissance: clarity, harmony, and order.

(left) Rembrandt van Rijn, Dutch, 1606 - 1669, Adam and Eve, 1638, etching, Rosenwald Collection, 1943.3.7102

(right) Albrecht Dürer, German, 1471 - 1528, Adam and Eve, 1504, engraving on laid paper, Gift of R. Horace Gallatin, 1949.1.18

Rembrandt's artistic goals are different: he focuses on the human emotions leading to the fall. His Adam and Eve are not idealized; their faces and bodies are lumpish and imperfect, drawn with strokes that emphasize bulges and knobby limbs. They are shown with loose hair falling in twisted coils. Rembrandt conveys their indecision, temptation, and fear through his eloquently drawn forms.

(left) Rembrandt van Rijn, Dutch, 1606 - 1669, Adam and Eve (detail), 1638, etching, Rosenwald Collection, 1943.3.7102

(right) Albrecht Dürer, German, 1471 - 1528, Adam and Eve (detail), 1504, engraving on laid paper, Gift of R. Horace Gallatin, 1949.1.18

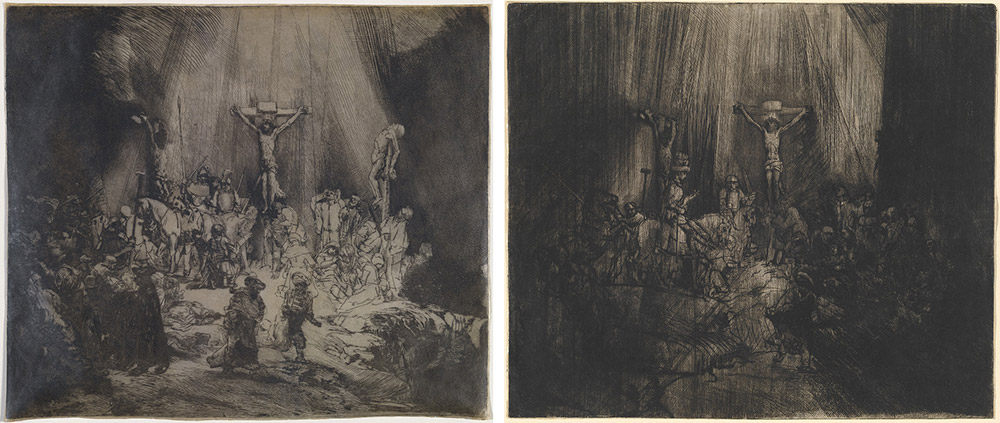

These two prints, each created almost entirely in drypoint, demonstrate Rembrandt's great technical skill as a printmaker. Using a heavy drypoint line, Rembrandt could describe figures and shapes quickly in outline, with little cross-hatching, giving the image a sense of urgency and drama.

Yet the burr that makes drypoint so velvety and atmospheric is also unpredictable. It prints differently each time the plate is inked and gradually wears away. An artist such as Rembrandt can take advantage of these changes, buffing the plate to remove figures and adding washes of ink to create dark tonal areas.

In a later state of this print, we can see how Rembrandt has removed some of the figures, reducing the scene to a stark, nightmarish vision.

(left) Christ Crucified between the Two Thieves (The Three Crosses), 1653, drypoint and burin, Gift of R. Horace Gallatin, 1949.1.50

(right) Christ Crucified between the Two Thieves (The Three Crosses), 1653, drypoint and engraving on laid paper, Rosenwald Collection, 1943.3.7174

Eighty-two of Rembrandt's copperplates survive today. After his death, unscrupulous dealers profited by using the plates to make unauthorized prints. Many of the plates have been eroded by this abuse. The National Gallery of Art's copperplate of Abraham Entertaining the Angels is unusual; it is perfectly preserved—the incised lines still contain Rembrandt's original ink.

Abraham Entertaining the Angels [recto], 1656, etched copperplate with drypoint, Gift of Ladislaus and Beatrix von Hoffmann and Patrons' Permanent Fund, 1997.85.1.a

The Artist

Rembrandt's life story has proven irresistible to biographers. Written documents allow us insight into the critical events of his life, and the many self-portraits he made let us follow him from youth to old age—a remarkable journey.

Born in Leiden in 1606, he first studied painting. In 1624, after three years of artistic training, he went to Amsterdam, where he studied briefly with the important history painter Pieter Lastman.

Self-Portrait Leaning on a Stone Sill, 1639, etching, Rosenwald Collection, 1943.3.9117

As a young artist, Rembrandt had great financial and social success. In 1634 he married Saskia van Uylenburgh, an intelligent young woman from a prominent family. Rembrandt borrowed heavily to buy a grand house for them.

Saskia van Uylenburgh, the Wife of the Artist, probably begun 1634/1635 and completed 1638/1640, oil on panel, Widener Collection, 1942.9.71

Their happiness was short-lived. Three of their children died in infancy. Their fourth child, Titus, survived, but tuberculosis led to Saskia's death in 1642, when Titus was only a year old. In this print, Rembrandt depicts the ill Saskia in bed.

Rembrandt's work began to change after Saskia's death. He moved away from a lively, extravagant, baroque style to a quieter, more reflective approach, in which poignant gestures and powerful contrasts of dark and light convey intense emotion. Commissions dropped off. He was criticized for his deeply personal manner of painting, the very quality that modern viewers find so compelling.

Saskia Lying in Bed, c. 1638, pen and ink, brush with brown wash on laid paper, Ailsa Mellon Bruce Fund, 1966.2.1

Personal troubles continued to mount. Geertje Dircx, Titus' nurse, became Rembrandt's companion. When he abandoned her, Geertje successfully sued him for breaking his promise to marry her. Rembrandt was ordered to pay her an annual stipend. His housekeeper, Hendrickje Stoffels, had already replaced Geertje as his companion.

An economic depression and Rembrandt's free spending—he was an avid art collector—worsened his financial situation. By 1656 Rembrandt was nearly bankrupt. Between 1656 and 1658 much of his property was auctioned off, perhaps including the copperplate for Abraham Entertaining the Angels.

Self-Portrait, 1659, oil on canvas, Andrew W. Mellon Collection, 1937.1.72

After settling with his creditors, Rembrandt moved to a modest house in a working-class neighborhood. He became increasingly isolated, supported by Hendrickje and his son Titus. The plague took Hendrickje's life in 1663. Five years later, Titus died, the victim of another plague epidemic.

Self-Portrait (detail), 1659, oil on canvas, Andrew W. Mellon Collection, 1937.1.72

Rembrandt van Rijn died on 4 October 1669 and was buried in an unmarked grave. The plate for Abraham Entertaining the Angels had been purchased by an unknown buyer and came into the hands of a Flemish artist, Pieter Gysels (1621-1690). Gysels painted a river landscape on the back of the plate; copper is an excellent surface for such small, detailed paintings. It is amazing to us today that this copperplate was once considered more valuable as the surface for a new work of art than as a work by Rembrandt.

Follower of Peeter Gysels, Flemish, 1621 - 1690, River Landscape with Villages and Travelers [verso], c. 1675/1685, oil on copper, Gift of Ladislaus and Beatrix von Hoffmann and Patrons' Permanent Fund, 1997.85.1.b

When a private collector decided to sell the painting by Gysels at auction in 1997, it was removed from its frame. Experts discovered the etched image on the reverse and identified it as Rembrandt's work. This recent addition to the Gallery's collection is considered to be one of the best preserved of all of Rembrandt's surviving plates—a rare treasure for the nation.

(left) Abraham Entertaining the Angels, 1656, etching and drypoint, Rosenwald Collection, 1943.3.7160

(right) Abraham Entertaining the Angels [recto], 1656, etched copperplate with drypoint, Gift of Ladislaus and Beatrix von Hoffmann and Patrons' Permanent Fund, 1997.85.1.a