Dan Flavin: A Retrospective

Introduction

One might not think of light as a matter of fact, but I do. And it is, as I said, as plain and open and direct an art as you will ever find.

—Dan Flavin, 1987

For more than three decades, Dan Flavin (1933-1996) vigorously pursued the artistic possibilities of fluorescent light. The artist radically limited his materials to commercially available fluorescent tubing in standard sizes, shapes, and colors, extracting banal hardware from its utilitarian context and inserting it into the world of high art. The resulting body of work at once possesses a straightforward simplicity and a deep sophistication.

Dan Flavin, untitled (in honor of Harold Joachim) 3, 1977, pink, yellow, blue, and green fluorescent light, 8 ft. (244 cm) square across a corner, Photo: Billy Jim, New York © Stephen Flavin/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Youth and Education

Flavin was born in Queens, New York, in 1933, where he went to parochial school, before attending (against his wishes) a preparatory school for the seminary in Brooklyn. In 1953, he enlisted in the Air Force and trained as a meteorological technician. Although Flavin sketched and drew from an early age, it was at this time, while working as a meteorological aide, that he began to spend most of his free time making art, visiting museums in Washington, D.C., and New York, and collecting art. In the late 1950s, the young Flavin attended Columbia University and studied the history of art, while working a series of jobs that included mailroom clerk at the Guggenheim Museum and guard at the Museum of Modern Art, and, later, the American Museum of Natural History. During this period, Flavin made important art world contacts and produced mixed media collages that included found objects from the streets, especially crushed cans.

Dan Flavin, Juan Gris in Paris (adieu Picabia), 1960-1962, crushed can, oil on Masonite, and acrylic on balsa, 19 7/8 x 24 x 3 3/16 in., Collection Stephen Flavin, Photo: Bill Jacobson, New York © Stephen Flavin/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Early Work and Icons

The first hint of Flavin's interest in fluorescent light is found in his 1961 poem that reads:

flourescent

poles

shimmer

shiver

flick

out

dim

monuments

of

on

and

off

art.

That same year he began work on his icons series, in which incandescent and fluorescent bulbs are attached to shallow, boxlike square constructions made from various materials such as wood, Formica, or Masonite. icon V (Coran’s Broadway Flesh) is one of the largest and brightest of the icons, with twenty-eight incandescent "candle" bulbs lining the perimeter of the central square. By using the term "icon" to describe these early light constructions, Flavin evokes the gold-ground religious icons of Byzantine art. But the term “icon” is used ironically, and hints at the artist’s ambivalence toward his Catholic upbringing; icon V lacks the reverence of a sacred object, and instead projects a kitschlike quality, not only in the use of the cheap incandescent bulbs, but also in the reference to the gaudy lights of Broadway.

Dan Flavin, icon V (Coran's Broadway Flesh), 1962, oil on cold gesso on Masonite, porcelain receptacles, pull chains, and clear incandescent "candle" bulbs, 41 5/8 x 41 5/8 x 9 7/8 in. (105.9 x 105.9 x 25.1 cm), Private collection, New York Photo: Bill Jacobson, New York © Stephen Flavin/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Early Work and Icons

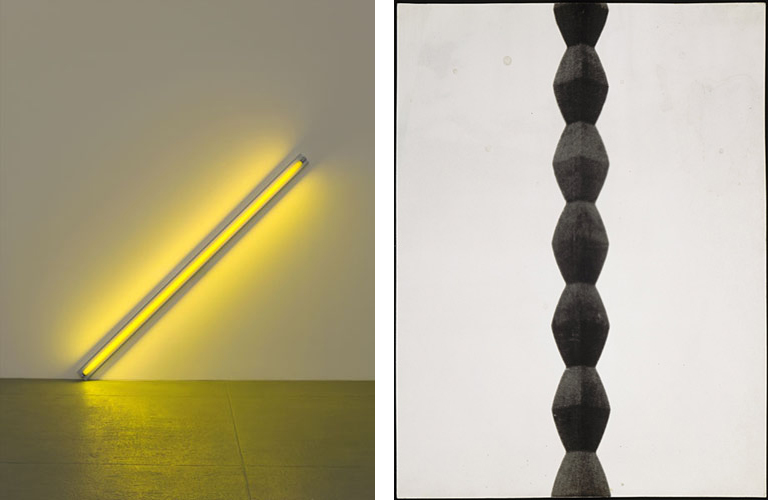

Flavin’s breakthrough with fluorescent light was the diagonal of May 25, 1963 (to Constantin Brancusi). In this seminal work—the artist’s first to use fluorescent light alone—Flavin eliminated the square box of the icons, and instead positioned a single, unadorned yellow fluorescent light at a 45-degree angle against a gallery wall. Struck by the result, Flavin declared the "gold" tube his "diagonal of personal ecstasy." He went on to describe that,

The radiant tube and the shadow cast by its supporting pan seemed ironic enough to hold alone. There was literally no need to compose this system definitively; it seemed to sustain itself directly, dynamically, dramatically in my workroom wall—a buoyant and insistent gaseous image which, through brilliance, somewhat betrayed its physical presence into approximate invisibility.

By declaring that a fluorescent light tube could stand on its own as a work of art, Flavin boldly yet simply challenged the history of art, in particular the discipline’s theoretical separation of art and everyday life. The critique follows in the philosophical footsteps of Marcel Duchamp, whose "readymades" of the early twentieth century consisted of ordinary, utilitarian objects (such as a bicycle wheel, bottle drying rack, or urinal) that Duchamp isolated from their functional context and placed within the environment of a work of art. In so doing, Duchamp deemed an object to be art by virtue of selection alone.

(left) Dan Flavin, the diagonal of May 25, 1963 (to Constantin Brancusi), 1963, yellow fluorescent light, 8 ft. (244 cm) long on the diagonal, Dia Art Foundation Photo: Billy Jim, New York © Stephen Flavin/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

(right) Marcel Duchamp, 1887-1968, Fountain 1917, replica 1964, porcelain, unconfirmed, 36 x 48 x 61 cm, Tate Gallery, London Purchased with assistance from the Friends of the Tate Gallery, 1999, Photo: Tate Gallery, London, Art Resource, NY

Early Work and Icons

Even as Flavin worked against the grain of art historical tradition, he also embraced it. The parenthetical dedication of the diagonal to Constantin Brancusi indicates his sentimental attachment to the modern Romanian sculptor. Indeed, Flavin not only dedicated the work to Brancusi, but directly compared his lone tube to Brancusi’s famous "endless column," in which he stacked repeating wedge-shaped metal forms. As Flavin explained, "Both structures had a uniform elementary visual nature, but they were intended to exceed their obvious visible limitations of length and their apparent lack of complication."

(left) Dan Flavin, the diagonal of May 25, 1963 (to Constantin Brancusi), 1963, yellow fluorescent light, 8 ft. (244 cm) long on the diagonal, Dia Art Foundation Photo: Billy Jim, New York © Stephen Flavin/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

(right) Constantin Brancusi, Romanian, 1876-1957, Endless Column at Targu Jiu, 1938, Gelatin-silver print, 15 5/8 x 11 3/4 in. (39.8 x 29.7 cm), Musée national d'art moderne, Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris, Photo: Philippe Migeat, Courtesy Réunion des Musées Nationaux / Art Resource, NY

Early Work and Icons

Another seminal early work is the nominal three (to William of Ockham), in which the artist positioned six, eight-foot daylight fluorescent tubes vertically in a one-two-three progression spaced evenly across a gallery wall. The radical simplicity of his medium and the presentation of the fluorescent tubes in a basic progression encouraged viewers to perceive even slight differences. This interest in so-called seriality was important not only for Flavin, but also for many of his contemporaries. Flavin dedicated the work to the medieval nominalist philosopher William of Ockham (c. 1285-?1349), famous for his dictum known as "Ockham’s Razor": "Entities should not be multiplied unnecessarily." That is, the simple answer is the better one. Here Flavin reduces the "entities" of his art to the simple visual vocabulary of pure fluorescent light.

Dan Flavin, the nominal three (to William of Ockham), 1963, cool white fluorescent light, 8 ft. (244 cm) high, Dia Art Foundation, Photo: Billy Jim, New York © Stephen Flavin/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Minimalism and Abstraction

Flavin’s fluorescent lights grew out of the traditions of post–World War II American art. In the 1950s, abstraction became the dominant mode of artistic expression, especially in New York, which was quickly establishing itself as an international art capital. The abstract expressionists, including such artists as Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning, Franz Kline, and Clyfford Still, produced nonobjective works that have a painterly quality to them: brushstrokes are visible, paint is allowed to drip and pool, and the artists’ energy and movement are manifest, sometimes aggressively so. Not all abstract, post-war painting favored the loose brushwork of gestural abstraction. Other abstract painters of this period, including Barnett Newman and Mark Rothko, painted large color fields that are often described in spiritual terms. These painters were of enormous significance for Flavin; for example, there is a parallel between Rothko’s luminous paintings with their glowing, hovering forms and the radiating colored lights of Flavin’s work.

Dan Flavin, the diagonal of May 25, 1963 (to Constantin Brancusi), 1963, yellow fluorescent light, 8 ft. (244 cm) long on the diagonal, Dia Art Foundation Photo: Billy Jim, New York © Stephen Flavin/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Minimalism and Abstraction

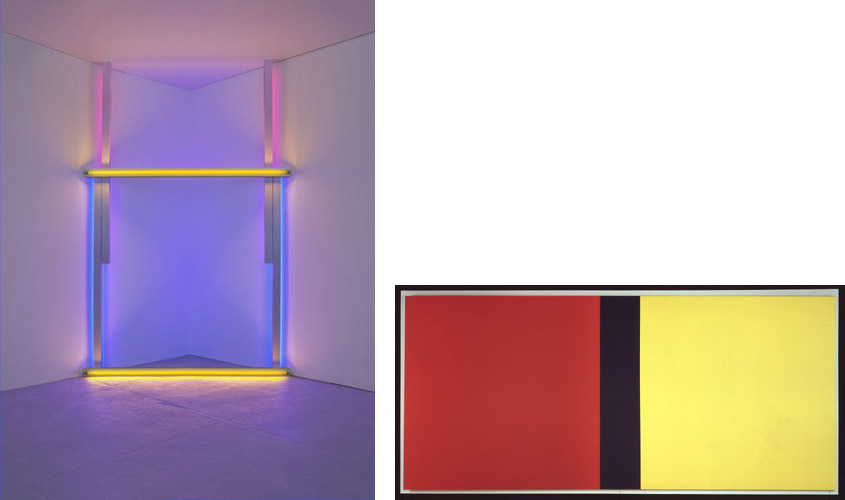

The thin, rigid lines of Flavin’s fluorescent tubes that articulate an otherwise blank gallery wall also relate to the paintings of Barnett Newman, in which a narrow band of pigment—a "zip"—cuts vertically across a flat field of contrasting color. Flavin’s deep regard for Newman is evident in several of his works, such as untitled (to Barnett Newman to commemorate his simple problem, red, yellow, and blue) whose title directly references some of Newman's final paintings. While Newman’s "zips" were praised for the way in which they established a new kind of pictorial space, Flavin went even further: His fluorescent lights actually bleed into the ambient space surrounding the fixture itself; the work of art, therefore, consists not merely of the fluorescent tubes, but also of the space they illuminate.

Newman was not only influential for Flavin, but his paintings were more broadly a precursor to minimalism, the movement to which Flavin’s art is often ascribed (although the artist himself never approved of the term). The minimalists drew on post-war tendencies in abstraction, and developed a cool, rational aesthetic, expressed through the use of industrial materials, the erasure of the artist’s hand from the object, and the implementation of neutral, geometric forms. Along with Flavin, leading minimalists included Flavin’s close friend Donald Judd, as well as other contemporaries such as Sol LeWitt and Carl Andre. The minimalists created objects that defied conventions of both painting and sculpture, a quality that distinguishes Flavin’s fluorescent light constructions. Like sculpture, the lights are three-dimensional objects, yet, like painting, they are often mounted flat against the gallery wall and involve the juxtaposition and mixing of colors.

(left) Dan Flavin, untitled (to Barnett Newman to commemorate his simple problem, red, yellow, and blue), 1970, yellow, blue, and red fluorescent light height variable, 8 ft. (244 cm) wide across a corner, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of the Barnett & Annalee Newman Foundation, in honor of Annalee G. Newman, and the Nancy Lee and Perry Bass Fund, Photo: Billy Jim, New York © Stephen Flavin/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. 2004.40.1

(right) Barnett Newman, American, 1905-1970, Who's Afraid of Red, Yellow and Blue IV, 1969-1970, acrylic on canvas, 108 x 239 in. (274 x 603 cm), Staatliche Museen Zu Berlin - Preussischer Kulturbesitz, Nationalgalerie und Freunde der Nationalgalerie, Berlin, Photo: Joerg P. Anders, Courtesy Bildarchiv Preussischer Kulturbesitz / Art Resource, NY, Barnett Newman Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS) New York

Hardware

Beginning in 1963, Flavin adopted commercially available fluorescent light as the primary medium for his art. Notably, he preferred standardized, utilitarian fluorescent light to custom-designed, showy neon. He confined himself to a limited palette (red, blue, green, pink, yellow, ultraviolet, and four different whites) and form (straight two-, four-, six-, and eight-foot tubes, and, beginning in 1972, circles). Within this restricted visual vocabulary he began a decades-long investigation into the behavior of light.

Dan Flavin, untitled (to Barnett Newman to commemorate his simple problem, red, yellow, and blue), 1970, yellow, blue, and red fluorescent light height variable, 8 ft. (244 cm) wide across a corner, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of the Barnett & Annalee Newman Foundation, in honor of Annalee G. Newman, and the Nancy Lee and Perry Bass Fund, Photo: Billy Jim, New York © Stephen Flavin/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. 2004.40.1

Hardware

Fluorescent light is produced by filling a glass tube with a mixture of mercury vapor and argon gases. When electrified, the gases emit an ultraviolet radiation that causes the phosphorescent compounds that coat the inside of the sealed glass tube to glow. Different phosphors radiate at different wavelengths, thereby producing the multiple colors. Because colored light behaves differently than pigment, Flavin’s works often defy the expectations of viewers, who are frequently surprised and amused by the discovery of the properties of light. For example, mixing colors across the spectrum in pigment renders paint black; blending the colors of the light spectrum results, instead, in white light. This effect is beautifully illustrated in untitled (to Henri Matisse) in which pink, yellow, blue, and green lights mix to produce an ambient white light. The work is dedicated to Henri Matisse, the radical colorist whom Flavin admired.

(left) Dan Flavin, untitled (to Henri Matisse), 1964, pink, yellow, blue, and green fluorescent light, 8 ft. (244 cm) high, Private collection, New York, Photo: Billy Jim, New York © Stephen Flavin/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

(right) Henri Matisse, Open Window, Collioure, 1905, oil on canvas, Collection of Mr. and Mrs. John Hay Whitney, 1998.74.7

Hardware

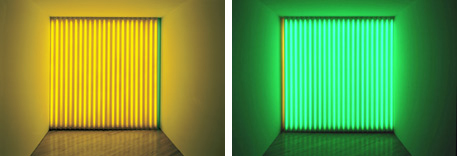

Primary colors also vary between pigment and light. For pigments the primaries are red, yellow, and blue, whereas for light they are red, blue, and green. (Green mixed with red makes yellow light). Flavin acknowledged this difference in greens crossing greens (to Piet Mondrian who lacked green), coyly dedicating a green light work to Mondrian—the Dutch modernist famous for his primary color palette. This work by Flavin also demonstrates another intriguing property of light: Green is the most brilliant fluorescent light, and its intensity can be so strong that it almost appears white. In contrast, fluorescent red is subdued. Because no mixture of phosphors can make a true red, the inside of the tube must be tinted, which in turn blocks the amount of emitted light. Thus, while red pigment is bold, red light, such as that seen in monument 4 for those who have been killed in ambush (to P.K. who reminded me about death), 1966, is muted. Here, then, the red suggests violence and bloodshed, yet the overall tone is subdued and elegiac rather than menacing.

(top left) Dan Flavin, greens crossing greens (to Piet Mondrian who lacked green), 1966, green fluorescent light, first section: 4 ft. (122 cm) high, 20 ft. (610 cm) wide, second section: 2 ft. (61 cm) high, 22 ft. (670 cm) wide, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, Panza Collection, 1991 © Solomon R.Guggenheim Museum, New York © Stephen Flavin/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

(bottom left) Dan Flavin, monument 4 for those who have been killed in ambush (to P.K. who reminded me about death), 1966, red fluorescent light, 8 ft. (244 cm) wide, 8 ft. (244 cm) deep, Dia Art Foundation, Photo: Cathy Carver © Stephen Flavin/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

(right) Piet Mondrian, Tableau No. IV; Lozenge Composition with Red, Gray, Blue, Yellow, and Black, c. 1924/1925, oil on canvas, Gift of Herbert and Nannette Rothschild, 1971.51.1

"monuments"

Flavin directly approached the genre of the monument in his large series, "monuments" for V. Tatlin, named for the artist Vladimir Tatlin (1885-1953). Tatlin was influential in post-1917 Russia, where he sought to use his art to uphold the utopian ideals of the revolution. Flavin was especially struck by Tatlin’s famous Monument to the Third International (1919-1920)—a project for a colossal, tilted iron tower surrounded by two spirals, containing rotating geometric glass halls. Never built, Tatlin’s monument became a symbol for ambitious yet unrealized utopian dreams.

Flavin’s "monuments" for V. Tatlin recall their namesake’s merging of art and technology and also speak to the Russian revolutionary’s call for "real materials in real space." As Flavin noted, "monument 7 in cool white fluorescent light memorializes Vladimir Tatlin, the great revolutionary, who dreamed of art as science. It stands, a vibrantly aspiring order, in lieu of his last glider, which never left the ground." Flavin’s "monument" series is deliberately ironic, however, for Flavin’s art is exceptionally "low tech," rejecting technological advances in favor of ordinary hardware. Flavin’s designation of the series as "monuments" (which he always used in quotations) is equally paradoxical, for the impermanence of the fluorescent lights (the bulbs will eventually burn out and need replacing) counters the traditions of monuments and memorials as eternal reminders.

(left) Dan Flavin, "monument" 1 for V. Tatlin, 1964, cool white fluorescent light, 8 ft. (244 cm) high, Dia Art Foundation, Photo: Billy Jim, New York © Stephen Flavin/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

(right) Vladimir Tatlin, Monument to the Third Interntaional, 1920, wood, cardboard, wire, metal, and oil paper approx. 16 ft. (500 cm) high Courtesy Anatolii Strigalev

Light, Space, and Architecture

Although Flavin’s earliest fluorescent works were installed on the walls like paintings, early on he began to explore the full space of the room, exploiting the overlooked margins. In 1964, at Flavin’s first solo exhibition at the Green Gallery in New York, for instance, the artist hung a primary picture at the edge of the gallery wall, adjacent to a doorway. In occupying the edge, where wall meets empty space, Flavin abandoned the conventional space of art and allowed the art object to address the interior in a new way. With an ironic twist, Flavin constructed the fluorescent lights as a rectangle surrounding a void, mimicking the shape of a picture frame and mocking the rigid traditions of art.

Dan Flavin, a primary picture, 1964, gold, pink and red, red fluorescent light, 2 ft. (61 cm) high, 4 ft. (122 cm) wide, Hermes Trust, U.K.; Courtesy of Francesco Pellizzi, Photo: Billy Jim, New York © Stephen Flavin/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Light, Space, and Architecture

In that same exhibition, the artist mounted pink out of a corner (to Jasper Johns). Placing this single, eight-foot pink fluorescent tube in the corner, literally illuminated what is, by convention, a darkened area of the installation space. Invigorating "dead space" with light became a powerful technique of the artist, as seen in the subtle tones of untitled (to the "innovator" of Wheeling Peachblow). The palette of this light construction takes its cue from the hues present in Wheeling Peachblow glass, a nineteenth-century glass (largely manufactured in Wheeling, West Virginia) with deep coral to luminous yellow coloration.

(left) Dan Flavin, pink out of corner (to Jasper Johns), 1963, pink fluorescent light, 8 ft. (244 cm) high, Collection Stephen Flavin, Photo: Billy Jim, New York © Stephen Flavin/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

(right) Dan Flavin, untitled (to the "innovator" of Wheeling Peachblow), 1966-1968, daylight, yellow, and pink fluorescent light, 8 ft. (244 cm) square across a corner, Photo: Billy Jim, New York © Stephen Flavin/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Light, Space, and Architecture

Flavin more thoroughly integrated his fluorescent light constructions with the surrounding architecture in his so-called "corridor" pieces, in which a series of parallel fluorescent tubes extend across the width of a hallway, thereby blocking access and forcing visitors to find an alternative pathway. In untitled (to Jan and Ron Greenberg), a corridor is obstructed by bars of light—green on one side, yellow on the other. A small open space between the last fluorescent tube and the wall permits a glimpse of the reverse color so that the primary color is tinged by the effects of the light spilling in from the back.

Dan Flavin, untitled (to Jan and Ron Greenberg), 1972-1973, yellow and green fluorescent light, 8 ft. (244 cm) high, in corridor measuring 8 ft. (244 cm) high and 8 ft. (244 cm) wide, length variable, Dia Art Foundation, Photo: Florian Holzerr, Munich

Light, Space, and Architecture

The construction untitled (to you, Heiner, with admiration and affection) embodies what fellow minimalist Donald Judd described as Flavin’s "interior articulation" of a space. Extending some 120 feet, the installation of this "green barrier" at the National Gallery of Art fills and redefines the space of the mezzanine terrace by imbuing the mezzanine with a glowing green hue, impeding visitors’ movement as they are forced to navigate around the monumental work and heightening their perception of the architecture.

Large-scale works became a focus of Flavin’s late career, with site-specific lights commissioned for such diverse locations as Frank Lloyd Wright’s spiral rotunda at the Guggenheim Museum, a converted nineteenth-century rail station in Berlin (now the Museum für Gegenwart), a converted church in Bridgehampton, New York (established in 1983 as the Dan Flavin Art Institute), and a church in Milan, the last completed posthumously. While the scale had increased, the hardware, aesthetic preoccupations, and ironic humor that Flavin demonstrated in his earliest light experiments were still evident. Dedicating virtually his entire career to the artistic possibilities of fluorescent light, Flavin concentrated his efforts in a way rarely seen in the history of art. Restricting his materials was not a limitation, but an enabler; he exploited subtle differences and found depth, meaning, and beauty in what others overlooked.

Written by Lynn Kellmanson Matheny, Exhibition Programs, National Gallery of Art

Dan Flavin, untitled (to you, Heiner, with admiration and affection), 1973, green fluorescent light modular units, each 4 ft. (122 cm) wide, length variable, Collection Stephen Flavin © Stephen Flavin/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York