All the Mighty World: The Photographs of Roger Fenton, 1852 - 1860

Introduction

The photographic career of Roger Fenton (1819-1869) lasted only eleven years, but during that time he became the most famous photographer in Britain. Part of the second generation of photographers who came to maturity in the 1850s—only a decade after the process was invented—Fenton strove to elevate the new medium to the status of a fine art and to establish it as a respected profession. He was the first official photographer to the British Museum and one of the founders of the Photographic Society, later named the Royal Photographic Society, an organization he hoped would help establish the medium's importance in modern life.

This exhibition takes its title, All the Mighty World, from William Wordsworth's 1798 "Lines Composed a Few Miles above Tintern Abbey," an ode to nature, in which the poet declares himself:

A lover of the meadows and the woods,

And mountains; and of all that we behold

From this green earth; of all the mighty world

Of eye and ear, both what they half-create,

And what perceive; . . .

Fenton himself photographed Tintern Abbey, and his landscapes reveal a reverence for nature that echoes Wordsworth's passion. These lines also suggest Fenton's belief that the perceptive eye of the camera could record "all the mighty world." Always exploring new subjects and testing the limits of his practice, Fenton photographed Britain's ruined abbeys and stately homes, Russian architecture, romantic landscapes, the collections of the British Museum, the Crimean War, the royal family, as well as "Orientalist scenes" and still lifes—all of which are represented in this exhibition.

Roger Fenton (1819 - 1869), Self-Portrait, February 1852, albumen silver print, 12.2 x 9 cm (4 13/16 x 3 9/16 in.), Gilman Paper Company Collection, New York

Early Views, 1854

Grandson of a wealthy industrialist, Roger Fenton was born in 1819 north of Manchester in Lancashire, England. In the early 1840s, he put aside his law studies to become an artist, studying painting in both Paris and London. In 1851, he took up photography and returned briefly to Paris to learn from the leading French photographer, Gustave Le Gray. Trained as a painter and committed to photography as an art, Le Gray had a lasting impact on Fenton's career.

Like Le Gray, Fenton sought to record "the living triumphs or the decaying monuments of man's genius and pride" in his photographs of architecture. But his early photographs also depict what he regarded as more English subjects, such as romantic landscapes that capitalized on the popularity of picturesque travel. His compositions often incorporate figures—surrogates for viewers—who walk amid the architectural ruins or gaze into the depths of sublime vistas.

Roger Fenton (1819 - 1869), Wharfe and Pool, Below the Strid, 1854, salted paper print, 34.5 x 28.2 cm (13 9/16 x 11 1/8 in.), Gilman Paper Company Collection, New York

Russia, 1852

In September 1852, Fenton traveled to Kiev, Russia, to record a suspension bridge that the English engineer Charles Blacker Vignoles was building over the Dnieper River for Czar Nicholas I. Fenton faced formidable challenges, especially for a novice photographer. He had to transport large quantities of photographic materials over several hundred miles and cope with the dim light and often bitter cold of the Russian autumn. That he made any photographs at all is a testament to his drive; that he did so successfully is an indication of how quickly he had mastered both the art and science of photography.

In addition to the bridge construction, Fenton made architectural views in Kiev, Moscow, and Saint Petersburg, as well as some landscapes. Recognizing that few photographs had been made of Russia's most famous buildings, he made several studies of the Kremlin and the Cathedral of the Assumption in Moscow, among others. He photographed the most prominent features of these buildings—the fortifications of the Kremlin or the onion domes of the Cathedral—but used unusual points of view to transform them into dynamic pictorial elements that energized his compositions.

Roger Fenton (1819 - 1869) Moscow, Domes of Churches in the Kremlin, 1852, salted paper print from paper negative, 18.2 x 21.2 cm (7 3/16 x 8 3/8 in.), Paul Mellon Fund, 2005.52.1

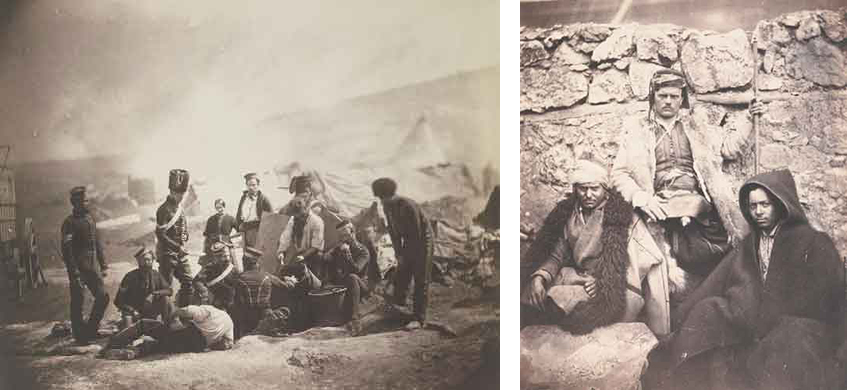

The Crimean War, 1855

After a long-simmering dispute over control of the Holy Lands, the Crimean War erupted in late 1853 when Russia moved into Turkish principalities on the Danube (present-day Romania). In retaliation, the English and French allied themselves with the Turks to capture the Russian naval base at Sebastopol on the Black Sea. The war drew great national attention, especially after the London Times published eyewitness reports detailing the abject suffering of the troops. Fenton sailed to the Crimea in February 1855, taking with him more than thirty crates of materials, as well as a wine merchant’s van that he outfitted as a portable darkroom in order to develop his negatives. The more than 350 photographs he made there are among the first war photographs ever created.

Armed with letters of introduction from Prince Albert, Fenton was granted exceptional access to the commanders of the English, French, and Turkish armies. In addition to portraits of military leaders, he recorded the local figures, such as the Group of Croat Chiefs, and made studies of camp life. Fenton’s photographs never violated Victorian taste by recording the horrors of battle—the dead bodies or the misery of the trenches. Instead, he sought to create a commercially viable portfolio of photographs that supported the belief that British soldiers had died with dignity in a noble cause.

(left) Roger Fenton (1819 - 1869), Cookhouse of the 8th Hussars, 1855, salted paper print, 15.9 x 20.3 cm (6 1/4 x 8 in.), The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

(right) Roger Fenton (1819 - 1869), Group of Croat Chiefs, 1855, albumen silver print, 19.2 x 16.5 cm (7 9/16 x 6 1/2 in.), Wilson Centre for Photography

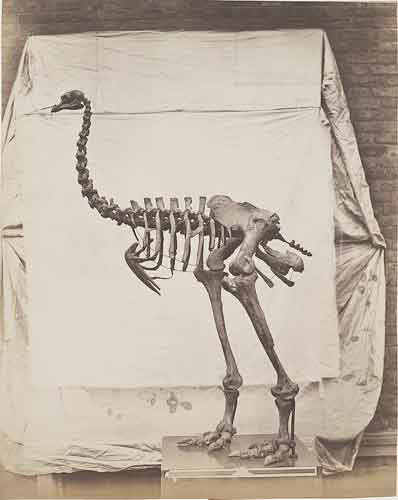

The British Museum, 1854–1858

In 1853, Fenton was hired as the first official photographer to the British Museum. Eager, in his own words, "to be connected with so useful an application of the photographic art," he forged a new path for photography, creating images that he knew would help the museum catalogue, classify, and also publicize its growing collection.

One of Fenton's greatest challenges was to illuminate the objects without artificial light. Portable works of art—Assyrian tablets or manuscripts—were brought to the roof of the museum, where Fenton had built a studio. He devised ingenious solutions to cope with harsh daylight shadows, such as placing his camera in a box with curtains to shield the lens from direct sunlight. With his assistants, he also made a remarkable number of prints for the museum—by May 1856 they had produced more than eight thousand.

Roger Fenton (1819 - 1869), Elephantine Moa (Dinornis elephantopus), an Extinct Wingless Bird in the Gallery of Fossils, British Museum, 1854-1858, salted paper print, 38.1 x 30.3 cm (15 x 11 15/16 in.), The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

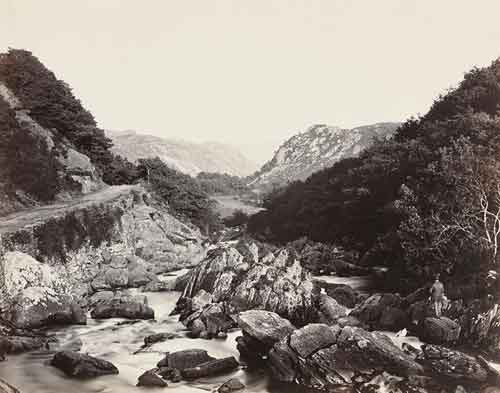

Excursions to Scotland and Wales, 1856-1857

In the late summer and early autumn of almost every year from 1852 to 1860, Fenton traveled throughout England, Scotland, and Wales to photograph the landscape and architecture. During his travels in Scotland in 1856, he experimented with the effects of light, atmosphere, and photographic space. Fenton frequently transformed what seemed like limitations of the camera and photographic materials into assets. Noting the camera's tendency to flatten space and obscure spatial relationships, he often based his compositions on shape and pattern.

In 1857, Fenton traveled to the heart of Wales—the valleys of the Conway, Lledr, and Llugwy. This area had been sparsely populated and little visited by English travelers until the late eighteenth century. Aided by new roads and attracted by rapturous descriptions in guidebooks, many artists visited the region in the 1840s and 1850s. Its rocky streams, wooded hollows, and mountainous expanses were considered both "sublime and beautiful" and inspired some of Fenton's finest landscape photographs.

Notably absent from Fenton's photographs of Wales are any of the region's new cast-iron and chain suspension bridges, engineering landmarks of the Industrial Revolution. Instead, he focused his camera on unassuming picturesque subjects, such as the old Pont-y-Pant Bridge (Bridge-of-the-Hollow), that seemed to embody the Welsh character and a simpler pastoral life.

Roger Fenton (1819 - 1869), Glyn Lledr, from Pont-y-Pant, 1857, albumen silver print, 34.2 x 43.5 cm (13 7/16 x 17 1/8 in.), H. H. Richardson Collection, Frances Loeb Library, Harvard Design School

Royal Portraits, 1855–1856

A critical factor in the development of Fenton's career was his relationship with Queen Victoria and Prince Albert, both of whom took a great interest in advances in science and technology and were intrigued with photography. They became patrons of the Photographic Society shortly after it was founded in 1853 and began to build what would become an important collection of photographs.

In 1854, Fenton escorted Queen Victoria and Prince Albert through the society's first exhibition. They were so impressed with his work that they purchased more than twenty-five of his Russian photographs and invited him to photograph the royal family on many occasions in the 1850s. In 1856, he went to Balmoral, their residence in Scotland, where he made several photographs of young princes and princesses. Because these photographs were never intended to be seen by the public but were for the queen's enjoyment, Fenton was allowed to record the very private moments of an excessively public family.

Roger Fenton (1819 - 1869), Prince Alfred, Duke of Edinburgh, 1856, salted paper print, 33.2 x 26 cm (13 1/16 x 10 1/4 in.), Courtesy of the Royal Photographic Society Collection at the National Museum of Photography, Film & Television, Bradford

Sacred and Secular Architecture, 1857 – 1858

Fenton made more photographs of architecture—sacred and secular, urban and rural—than almost any other subject. Rather than exploring new sites, he preferred the time-wracked abbeys and weathered cathedrals popularized through travel books, paintings, and prints. Often he captured distant views that integrated the buildings into their natural surroundings. Moving his camera closer, he also highlighted architectural pattern and detail, frequently including figures to give a sense of scale or to animate the scenes.

Fenton also photographed important civic buildings, including the Houses of Parliament. Works like Westminster from Waterloo Bridge demonstrate his remarkable ability to draw the viewer's eye into the depths of his composition. Collectively, Fenton's architectural studies celebrate the accomplishments of generations of British architects and attest to the deep national pride that infused nineteenth-century British society.

(top) Roger Fenton (1819 - 1869), Westminster from Waterloo Bridge, c. 1858, salted paper print, 30.3 x 42.2 cm (11 15/16 x 16 5/8 in.), Collection Centre Canadien d'Architecture-Canadian Centre for Architecture, Montréal

(bottom) Roger Fenton (1819 - 1869), Houses of Parliament, c. 1858, albumen silver print, 34 x 41.7 cm (13 3/8 x 16 7/16 in.), Courtesy of the Royal Photographic Society Collection at the National Museum of Photography, Film & Television, Bradford

Orientalist Studies, 1858

In 1858, Fenton made a series of fifty photographs that have come to be known as his Orientalist studies. An increasing European involvement in Near Eastern affairs during the previous decades had prompted a growing fascination with the culture of the region. Artists responded to this heightened interest with paintings of generalized Orientalist themes. Their images tended to be shaped more by imagination than reality, as romantic painters such as Delacroix envisioned a world characterized by visual splendor, sensuality, and exotic ritual. Fenton’s own Orientalist works adopted much of the same pictorial vocabulary.

To make these photographs, Fenton transformed his studio in north London into an exotic environment where musicians wearing loose- fitting garments lounged on low divans with ample pillows. The languid atmosphere of the scenes, coupled with the relaxed postures and intimate behavior of his models—unthinkable in Victorian sitting rooms—reveal the nineteenth-century misconception of the Near East as a place free from inhibitions and responsibilities.

Roger Fenton (1819 - 1869), Pasha and Bayadère, 1858, albumen silver print, 45 x 36.3 cm (17 11/16 x 14 5/16 in.), The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

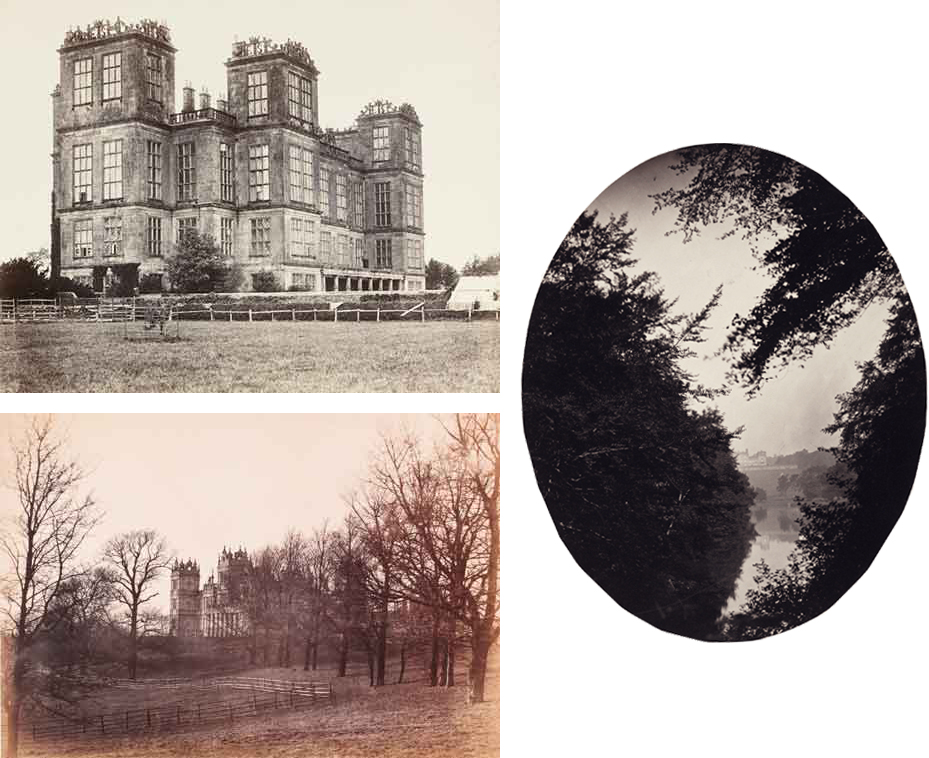

Stately Homes and Landscapes, 1858 – 1860

In the late 1850s, Fenton focused his interest in architecture on Britain's stately country houses, photographing Hardwick Hall and Wollaton Hall, both built in the late sixteenth century; neoclassical Harewood House of the eighteenth century; and Mentmore House, completed for the Baron de Rothschild only a few years before Fenton photographed its billiard room. The proud owners undoubtedly delighted in having Fenton, the most celebrated photographer in Britain, record their homes. He used the opportunities to offer glimpses into the lives of upper-class Victorians and reveal British prosperity and pride.

In 1860, Fenton traveled to the Lake District, a favorite tourist destination celebrated for its beauty by British painters and poets, most notably its native son Wordsworth. At the time, travel guides frequently included extensive quotations from literary and poetic descriptions of the area, which served as both a guide to the region and a souvenir of its pleasures. Fenton and other photographers realized that their photographs could function in much the same way, and he recorded many of the principal tourist destinations, including the Newby Bridge and Lake Derwentwater.

(top left) Roger Fenton (1819 - 1869), Hardwick Hall, from the South East, 1858, albumen silver print, 34.5 x 44 cm (13 9/16 x 17 5/16 in.), H. H. Richardson Collection, Frances Loeb Library, Harvard Design School

(bottom left) Roger Fenton (1819 - 1869), Wollaton Hall, c. 1859, albumen silver print, 30.16 x 43.82 cm (11 7/8 x 17 1/4 in.), Richard and Ronay Menschel

(right) Roger Fenton (1819 - 1869), Harewood House, Yorkshire, 1859, albumen silver print, 28.4 x 23.1 cm (11 3/16 x 9 1/8 in.), Courtesy of the Royal Photographic Society Collection at the National Museum of Photography, Film & Television, Bradford

Late Works, 1859 – 1860

In the late 1850s and early 1860s, Fenton's work became ever more ambitious, as he tackled new subjects and enervated older, more familiar ones. In 1859 he made several photographs of Stoneyhurst College, a Jesuit school whose property abutted the large landholdings of Fenton's extended family. His studies of the region's waterways frequently include figures fishing or contemplating the vistas before them and express the deep connection Fenton felt to his native land.

In the summer of 1860, Fenton turned his attention to still lifes, a subject that had become popular in mid-nineteenth-century British painting but was quite new to photography. Drawing on the lessons in lighting and composition that he had learned at the British Museum, he made more than forty detailed studies of objects in dense arrangements. Lush and sensuous, Fenton's still lifes often include exotic fruits and flowers—pineapples from the Caribbean, for example—that were imported from the far reaches of the British Empire or cultivated in nearby greenhouses.

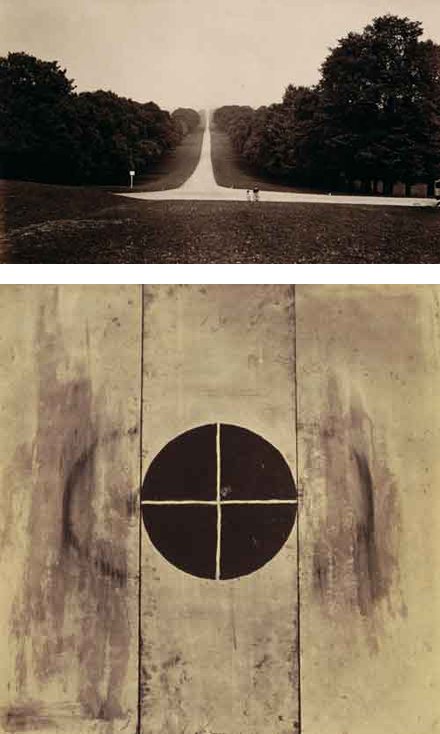

That same summer, Fenton went to Windsor and made one of his most radical compositions to date: the minimal, boldly dynamic The Long Walk. Queen Victoria provoked another equally modern composition, The Queen's Target, made just after she fired the first shot at the National Rifle Association at Wimbledon Common.

(top) Roger Fenton (1819 - 1869), The Long Walk, 1860, albumen silver print, 17.5 x 29.4 cm (6 7/8 x 11 9/16 in.), Lent by Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II

(bottom) Roger Fenton (1819 - 1869), The Queen's Target, 1860, albumen silver print, 21.6 x 21.3 cm (8 1/2 x 8 3/8 in.), Museum Ludwig, Cologne, Collection Robert Lebeck

Final Years

In 1862, Fenton abandoned photography, most likely for both personal and professional reasons. His only son had died in April 1860, and the family mill that had helped to support his comfortable lifestyle closed later that year. In addition, photography itself had changed markedly in the late 1850s and early 1860s. As hundreds of thousands of small, cheap photographs flooded the market, prices for all photographs plummeted, and Fenton, like many others, could not compete. As a result of this market change, respect for the profession, which Fenton had tried so hard to elevate, also diminished considerably.

In October 1862, Fenton announced his retirement from photography. The following month, he sold all of his equipment and negatives at an auction to remove "all that might be a temptation to revert to past occupations." Fenton returned to the practice of law and died in 1869 at the age of fifty.

(clockwise from top left)

Decanter and Fruit, 1860, albumen silver print, 41.7 x 35.2 cm (16 7/16 x 13 7/8), 55.3 x 44.1 cm (21 3/4 x 17 3/8), 68.5 x 53.2 cm (26 15/16 x 20 15/16), Courtesy of the Royal Photographic Society Collection at the National Museum of Photography, Film & Television, Bradford

Paradise, View down the Hodder, Stonyhurst, 1859, albumen silver print, 28 x 28 cm (11 x 11), Wilson Centre for Photography

Ely Cathedral, East End, 1857, albumen silver print, sheet: 41.4 x 35.7 cm (16 5/16 x 14 1/16), mount: 69.2 x 50.8 cm (27 1/4 x 20), Collection Centre Canadien d'Architecture/ Canadian Centre for Architecture, Montréal

Skeleton of Man and of the Male Gorilla (Troglodytes Gorilla) I, 1854-1858, salted paper print, 36.5 x 28 cm (14 3/8 x 11), 57 x 47 cm (22 7/16 x 18 1/2), 34.9 x 27.6 cm (13 3/4 x 10 7/8), Victoria and Albert Museum

The Princess Royal and Princess Alice, 1855, salted paper print, 33.7 x 30.5 cm (13 1/4 x 12), 68.4 x 53.2 cm (26 15/16 x 20 15/16), Courtesy of the Royal Photographic Society Collection at the National Museum of Photography, Film & Television, Bradford

Captain Lord Balgonie, Grenadier Guards, 1855, salted paper print, 16.5 x 20 cm (6 1/2 x 7 7/8), Wilson Centre for Photography