Jackson Pollock spent his formative years in Wyoming (he was born in Cody) and California. By the time he was 14 years old he had made an “art gallery” in a chicken coop on the family’s property. Eager to succeed in the art world, he moved to New York City when he was 18. There, he studied under the realist painter Thomas Hart Benton and visited museums—particularly the Metropolitan Museum and the Museum of Modern Art. He worked in various directions, inspired by Pablo Picasso, the Mexican muralists, surrealists including Joan Miró, Native American pictographic art, and old masters Michelangelo, Peter Paul Rubens, and El Greco—while he mastered the powers of line, marking, and abstracted form. Bouts of depression and drinking, however, made New York City a dangerous and tempting environment for him.

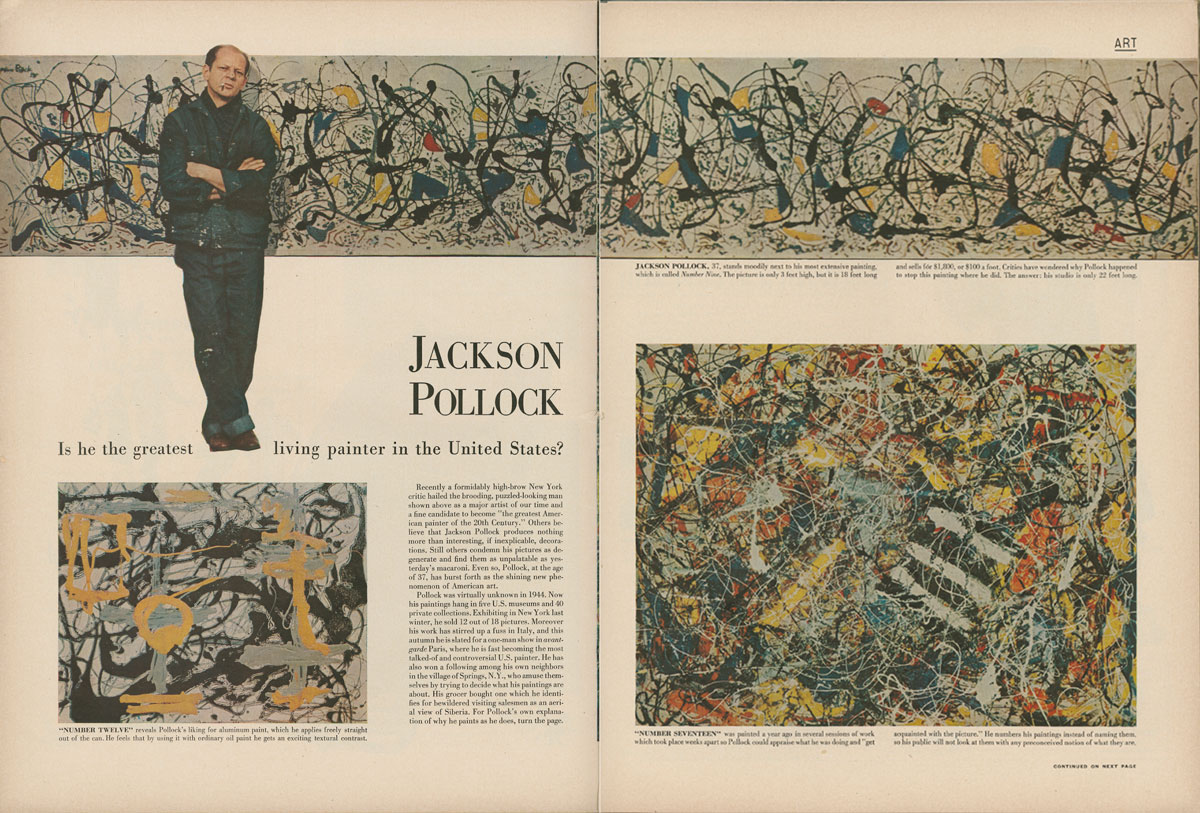

LIFE, August 8, 1949, pp 42-43

Pollock’s move from dark horse to darling of the art world came out of various concurrences: the powerful art critic Clement Greenberg’s insistence that Pollock’s work represented a new, authentic American art; a shift in the art world; and Pollock’s success, achieved over a period of years, at making gesture, line, texture, and composition the very subject of his canvases.

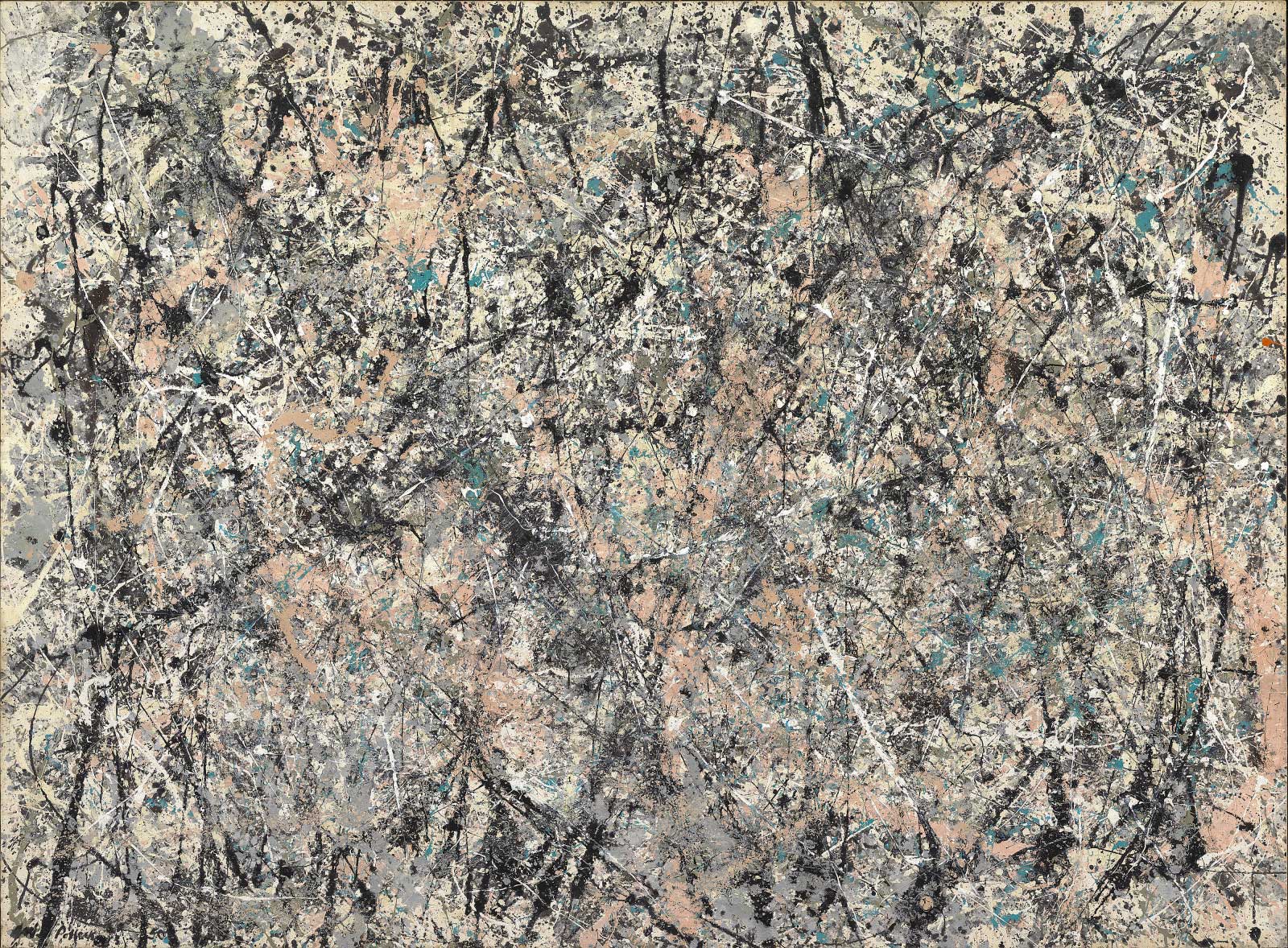

Pollock’s method was based on his earlier experiments with dripping and splattering paint on ceramic, glass, and canvas on an easel. Now, he laid a large canvas on the floor of his studio barn, nearly covering the space. Using house paint, he dripped, poured, and flung pigment from loaded brushes and sticks while walking around it. He said that this was his way of being “in” his work, acting as a medium in the creative process. For Pollock, who admired the sand painting of the American Indians, summoning webs of color to his canvases and making them balanced, complete, and lyrical, was almost an act of ritual. Like an ancient cave painter, he “signed” Lavender Mist in the upper left and right corners with his handprints.

Though the work contains no lavender, the webs of black, white, russet, orange, silver, and stone blue industrial paints in Lavender Mist radiate a mauve glow that inspired Greenberg, Pollock’s stalwart champion, to suggest the descriptive title, which Pollock accepted. Pollock’s canvases from this decisive phase of his career are considered to have transformed the experience of looking “at” a work of art into one of being immersed, upright, in its fullness. His mastery of chance, intuition, and control brought abstract expressionism to a new level.

About the Artist

Hans Namuth, Jackson Pollock, 1950, gelatin silver print, Diana and Mallory Walker Fund, 2008.13.1

In 1945 Pollock and his wife, artist Lee Krasner, moved to East Hampton on the far end of Long Island, whose light, air, and exquisite coastal geography had drawn a number of artists. There, Pollock had his breakthrough with the all-over abstract canvases that electrified the art world. Many of these works twist and sing with the rhythms of the grasses and light on the far East End, freeing painting from its figurative tasks.

Perennially short on money, Pollock had come to rely on bartering art for groceries at the nearby general store (still operating to this day). In August 1956, on one of his drives along the slim, winding roads that lace the East End, a drunken Pollock smashed into a tree, killing himself and a female passenger. By then he seemed to have lost the energy and focus he had brought to his signature works, but they left no question about his contribution to modernism by shifting artistic practice to focus on the relationships of painting to the body (the artist) and the world (the observer).

Related Works in the National Gallery of Art Collection

Jackson Pollock, Number 7, 1951, 1951, enamel on canvas, Gift of the Collectors Committee, 1983.77.1

Jackson Pollock, Untitled, c. 1950, black ink, Ailsa Mellon Bruce Fund, 1985.62.2

Jackson Pollock, Untitled, 1951, ink on Japanese paper, Gift of Ruth Cole Kainen, 2012.92.123

Jackson Pollock, Untitled, 1951, ink on Japanese paper, Gift of Ruth Cole Kainen, 2012.92.123

Abstract Expressionism in the

National Gallery of Art Collection

Explore all Collection Highlights