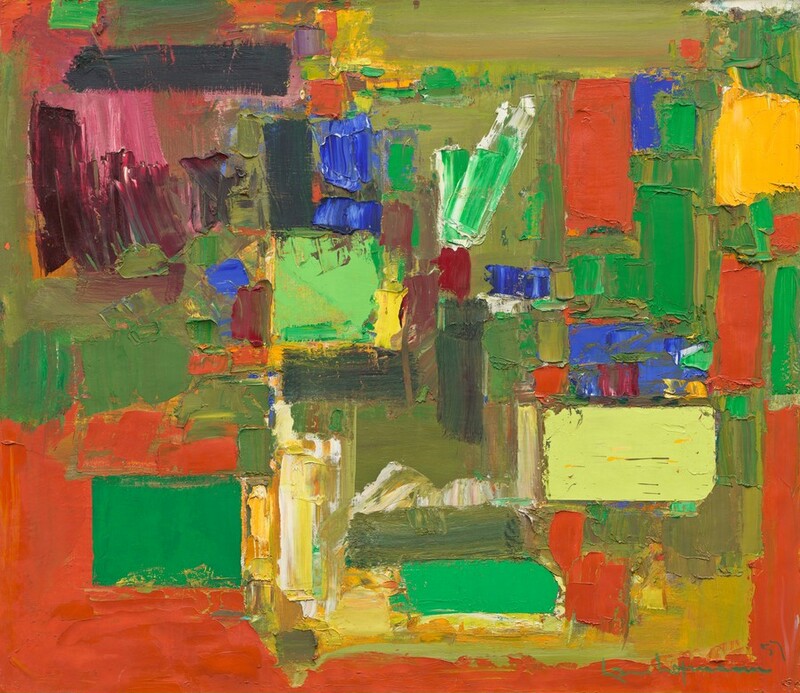

Autumn Gold

1957

Hans Hofmann

Painter, American, born Germany, 1880 - 1966

Autumn Gold is an important example of Hofmann's most familiar body of work. These images are distinguished by heavy rectangular slabs of intense, unmodulated colors that hover or superimpose themselves on the surface of the picture and are, in certain places, secured by thick, vigorous passages in a lower key. In Autumn Gold, incipient rectangles of color have been formed from the smaller dabs that Hofmann used in previous works, but here greatly enlarged. The rectangular forms first materialized in 1957, the year in which Hofmann created Autumn Gold; the following year, they would become more sharply defined, although painterly edges would continue to appear. In the words of the New York critic Clement Greenberg, Hofmann's commanding idiom was composed of a "fat, heavy, and eloquent surface" on which color is "saturated corporeally as well as optically." In his paintings, "presence" is related to "the picture's concentrated radiance, its effulgence and plenitude as an identity." [1]

Hofmann had been teaching art since 1915 (when he opened an art school in Munich), and, throughout his life, formal principles in his work were rigorously applied. The slabs—some created with a palette knife—possess a flat, aggressive opacity that is unique to the artist, while an impression of shallow pictorial space is created by subtle and deliberately calibrated adjustments of scale, by the relationship between colors, and by variations in tint and tone. Hofmann's work from this period is governed by a dynamic interaction of form, color, and material that he characterized as one of "push and pull." [2] The premise, which Hofmann explained in numerous notes, is that the compositions represent a tension between mere flatness (which is "passive") and illusive depth (which is "sterile"). This tension was achieved by using purely pictorial means in order to approximate the perceptual and psychological experience of depth in nature. The result, for Hofmann, is a pictorial space that is "alive, dynamic, fluctuating and ambiguously dominated by forces and counter-forces, by movement and counter-movement, all of which summarize into rhythm and counter-rhythm as the quintessence of life experience." [3] Hofmann shared his quasi-utopian faith in the emotional or spiritual resonance of abstract form with the early pioneers of nonobjective art. His strict formal principles were, in turn, a significant model for many abstract painters in New York, where Hofmann had settled in 1934.

(Text by Jeffrey Weiss, published in the National Gallery of Art exhibition catalogue, Art for the Nation, 2000)

Notes

1. Clement Greenberg, Hofmann (Paris, 1961), 28-34.2. Hans Hofmann, "The Resurrection of the Plastic Arts," originally published in the catalogue for Hofmann's 1954 exhibition at the Samuel M. Kootz Gallery, New York; reprinted in Sam Hunter, Hans Hofmann (New York, 1963), 44.3. Hunter 1963, 44.

East Building Upper Level, Gallery 403

Artwork overview

-

Medium

oil on canvas

-

Credit Line

-

Dimensions

overall: 132.7 x 153.4 cm (52 1/4 x 60 3/8 in.)

framed: 136.5 x 157.5 x 4.4 cm (53 3/4 x 62 x 1 3/4 in.) -

Accession Number

1996.81.4

More About this Artwork

Article: Celebrate Fall Foliage with Autumn Art at the National Gallery

Explore our bounty of fall images.

Artwork history & notes

Provenance

(Samuel M. Kootz Gallery, New York); sold 1958 to Robert and Jane Meyerhoff, Phoenix, Maryland;[1] gift 1996 to NGA.

[1] Provenance from The Robert and Jane Meyerhoff Collection: 1945 to 1995, Exh. cat., National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., 1996: 241.

Associated Names

Exhibition History

1959

New Paintings and Sculpture from Established and Newly Formed Baltimore Collections, Baltimore Museum of Art, 1959.

1960

Quattro Artisti Americani: Guston, Hofmann, Kline, Roszak, 30th Esposizione Biennale Internazionale D'Arte, Venice, 1960, no. 16.

1964

Selections from the Robert and Jane Meyerhoff Collection, Goucher College, Towson, Maryland, 1964.

1966

Selections from the Robert and Jane Meyerhoff Collection, Baltimore Museum of Art, 1966.

1973

Selections from the Robert and Jane Meyerhoff Collection, Baltimore Museum of Art, 1973.

1976

Hans Hoffmann: A Retrospective Exhibition, Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Washington, D.C.; Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, 1976-1977, fig. 32.

1996

The Robert and Jane Meyerhoff Collection: 1945 to 1995, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., 1996, no. 37, color repro.

2000

Art for the Nation: Collecting for a New Century, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., 2000-2001, unnumbered catalogue, repro.

2009

The Robert and Jane Meyerhoff Collection: Selected Works, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., 2009-2010, pl. 3.

2014

Modernism from the National Gallery of Art: The Robert and Jane Meyerhoff Collection, Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, de Young Museum, 2014, pl. 28.

Bibliography

1996

The Robert and Jane Meyerhoff Collection: 1945 to 1995. Exh. cat. National Gallery of Art, Washington, 1996: no. 37.

Inscriptions

lower right: hans hofmann 57; on reverse: hans hofmann 1957

Wikidata ID

Q20194925