Willem Coymans

1645

Frans Hals

Artist, Dutch, c. 1582/1583 - 1666

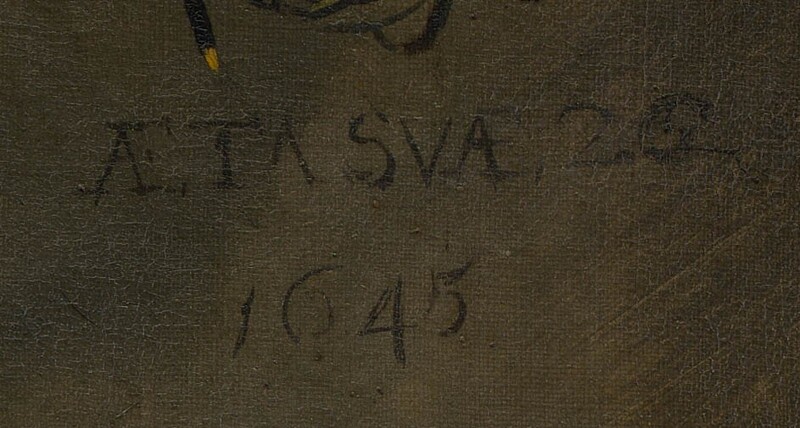

The crest bearing three cows’ heads, visible on the wall behind the sitter, indicates that this young man is a member of the prosperous Coymans family of Haarlem. The cows’ heads refer directly to the Dutch family name, which translates as "cow man." Archival and genealogical information, combined with the Latin inscription "AETA SVAE.22 / 1645" below the shield, identifies the sitter as Willem Coymans, who was twenty-two years old in 1645. The few paintings dated by Frans Hals tend to also provide the subjects’ ages, thus serving as genealogies. In addition to this likeness of Willem, Hals painted the portraits of at least four other members of the Coymans family.

Hals was the preeminent portrait painter in Haarlem, the most important artistic center of Holland in the early part of the seventeenth century. He was famous for his uncanny ability to portray his subjects with relatively few bold brushstrokes, and often used informal poses to enliven his portraits. Here, Willem Coymans is informally seated in a chair, with one arm hooked casually over its back to enhance the lifelike quality of his portrait. Coymans, resplendent in his elegant clothes, sports a brocaded jacket with slit sleeves over a pleated white shirt. The dazzling brushwork so typical of Hals is especially evident in the gold embroidery and the crispness of the sleeve. The pom-pom on his hat, pushed forward at a rakish angle, and the oversized collar of his shirt mark Willem as a dandy.

West Building Main Floor, Gallery 46

Artwork overview

-

Medium

oil on canvas

-

Credit Line

-

Dimensions

overall: 77 × 64 cm (30 5/16 × 25 3/16 in.)

framed: 102.24 × 89.85 × 7.62 cm (40 1/4 × 35 3/8 × 3 in.) -

Accession Number

1937.1.69

More About this Artwork

Artwork history & notes

Provenance

Coymans family, Haarlem. Mrs. Frederick Wollaston, London. (Sedelmeyer Gallery, Paris), before 1894; Rodolphe Kann [d. 1905], Paris, by 1897; purchased 1907 with the entire Kann collection by (Duveen Brothers, Inc., London, New York, and Paris); sold to Arabella D. [Mrs. Collis P.] Huntington [c. 1850-1924], New York; by inheritance to her son, Archer M. Huntington [1870-1955], New York; purchased 17 May 1928 by (Duveen Brothers, Inc.);[1] sold 7 May 1929 to Andrew W. Mellon, Pittsburgh and Washington, D.C.; deeded 28 December 1934 to The A.W. Mellon Educational and Charitable Trust, Pittsburgh; gift 1937 to NGA.

[1] Duveen Brothers Records, accession number 960015, Research Library, Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles: reel 322, box 467, folder 2 (copies in NGA curatorial files).

Associated Names

Exhibition History

1909

The Hudson-Fulton Celebration, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 1909, no. 37, as Balthasar Coymans.[1]

1928

1928 International Exhibition of Antiques and Art, Olympia, London, 1928, no. X22, as Portrait of Young Koeymanszoon van Ablasserdam.

1939

Masterworks of Five Centuries, The Golden-Gate International Exposition, San Francisco, 1939, no. 80a, repro., as Portrait of Balthasar Coymans, Alderman of Haarlem.

1989

Frans Hals, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.; Royal Academy of Arts, London; Frans Halsmuseum, Haarlem, 1989-1990, no. 61, repro.

2000

Like Father, Like Son? Portraits by Frans Hals and Jan Hals, North Carolina Museum of Art, Raleigh, 2000, pl. 1.

2003

Loan for display with permanent collection, The National Gallery, London, 2003-2004.

2007

Dutch Portraits: The Age of Rembrandt and Frans Hals, The National Gallery, London; Royal Picture Gallery Mauritshuis, The Hague, 2007-2008, no. 24, repro.

2021

Frans Hals: the Male Portraits, Wallace Collection, London, 2021 - 2022, no. 10, repro.

Bibliography

1897

Moes, Ernst Wilhelm. Iconographia Batava. 2 vols. Amsterdam, 1897-1905: 1(1897):205, no. 1779, as Balthasar Coymans.

1898

Sedelmeyer, Charles. Illustrated Catalogue of 300 Paintings by Old Masters of the Dutch, Flemish, Italian, French, and English schools, being some of the principal pictures which have at various time formed part of the Sedelmeyer Gallery. Paris, 1898: 66, no. 54, repro., as Koeymanszoon van Ablasserdam.

1900

Bode, Wilhelm von. Gemälde-sammlung des Herrn Rudolf Kann in Paris. Vienna, 1900: xviii, pl. 49, as Koeymanszoon van Ablasserdam.

1907

Hofstede de Groot, Cornelis. A Catalogue Raisonné of the Works of the Most Eminent Dutch Painters of the Seventeenth Century. 8 vols. Translated by Edward G. Hawke. London, 1907-1927: 3(1910):53, no. 168.

Sedelmeyer, Charles. Catalogue of Rodolphe Kann Collection. 2 vols. Paris, 1907: 1:13, 42, no. 40, repro., as Portrait of Young Koeijmanszoon van Ablasserdam.

1908

Grant, J. Kirby. "Mrs. Collis P. Huntington’s Collection." The Connoisseur 20 (January 1908): 3 fig. 1, 4, as Young Koeijmanszoon van Ablasserdam.

Holmes, Charles John. "Recent Acquisitions by Mrs. C. P. Huntington from the Kann Collection." The Burlington Magazine 12 (January 1908 ): 195-205, repro., as Young Koeijmanszoon of Ablasserdam.

Lennep, John C. van. "Portraits in the Kann Collection." The Burlington Magazine 13, no. 65 (August 1908): 293-294.

1909

"A Portrait by Hals at the Grafton Galleries." The Burlington Magazine 16 (October 1909): 109-110, as Johan Koeijmans.

Moes, Ernst Wilhelm. Frans Hals: sa vie et son oeuvre. Translated by J. de Bosschere. Brussels, 1909: 101, no. 27.

Valentiner, Wilhelm R. Catalogue of a collection of paintings by Dutch masters of the seventeenth century. The Hudson-Fulton Celebration 1. Exh. cat. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 1909: xv, 38, no. 37, repro., 154, 159, as Balthasar Coymans, Alderman of Haarlem.

1910

Valentiner, Wilhelm R. "Die Ausstellung holländischer Gemälde in New York." Monatshefte für Kunstwissenschaft 3 (1910): 6, 7 n. 5, as "not Joseph Coymans."

Valentiner, Wilhelm R. Catalogue of a Loan Exhibition of Paintings by Old Dutch Masters Held at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in Connection with the Hudson-Fulton Celebration. New York, 1910: 6, 145, no. 37, repro. 144., as Balthasar Coymans, Alderman of Haarlem.

1914

Bode, Wilhelm von, and Moritz Julius Binder. Frans Hals: Sein Leben und seine Werke. 2 vols. Berlin, 1914: 2:65, no. 245, pl. 155a.

Bode, Wilhelm von, and Moritz Julius Binder. Frans Hals: His Life and Work. 2 vols. Translated by Maurice W. Brockwell. Berlin, 1914: 2:19, no. 245, pl. 155a.

1921

Valentiner, Wilhelm R. Frans Hals: des meisters Gemälde in 318 Abbildungen. Klassiker der Kunst in Gesamtausgaben 28. Stuttgart and Berlin, 1921: 319, no. 212, repro.

1923

Valentiner, Wilhelm R. Frans Hals: des Meisters Gemälde in 322 Abbildungen. Klassiker der Kunst in Gesamtausgaben 28. 2nd ed. Stuttgart, Berlin, and Leipzig, 1923: 320, no. 225, repro.

1930

Dülberg, Franz. Frans Hals: Ein Leben und ein Werk. Stuttgart, 1930: 178-180, repro.

1936

Valentiner, Wilhelm R. Frans Hals Paintings in America. Westport, Connecticut, 1936: no. 82, repro.

1937

Cortissoz, Royal. An Introduction to the Mellon Collection. Boston, 1937: 40.

1939

Golden Gate International Exposition. Masterworks of Five Centuries. Exh. cat. Golden Gate International Exposition, San Francisco, 1939: no. 80a, repro., as Portrait of Balthasar Coymans, Alderman of Haarlem.

1941

Duveen Brothers. Duveen Pictures in Public Collections of America. New York, 1941: no. 194, repro., as Portrait of Balthasar Coymans.

Preliminary Catalogue of Paintings and Sculpture. National Gallery of Art, Washington, 1941: 95, no. 69, as Balthasar Coymans.

1942

National Gallery of Art. Book of illustrations. 2nd ed. Washington, 1942: 69, repro. 24, 240, as Balthasar Coymans.

1944

Cairns, Huntington, and John Walker, eds. Masterpieces of Painting from the National Gallery of Art. Translated. New York, 1944: 96, color repro., as Balthasar Coyman_.

1949

National Gallery of Art. Paintings and Sculpture from the Mellon Collection. Washington, 1949 (reprinted 1953 and 1958): 77, repro., as Balthasar Coymans.

1956

Walker, John. National Gallery of Art, Washington. New York, 1956: 44, repro.. as Balthasar Coymans.

1958

Slive, Seymour. "Frans Hals’ Portrait of Joseph Coymans." Wadsworth Atheneum Bulletin 4 (Winter 1958): 13-23, fig. 10.

1960

The National Gallery of Art and Its Collections. Foreword by Perry B. Cott and notes by Otto Stelzer. National Gallery of Art, Washington (undated, 1960s): 20, as Balthasar Coymans.

1963

Walker, John. National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. New York, 1963 (reprinted 1964 in French, German, and Spanish): 178, repro.

Beeren, Willem. Frans Hals. New York, 1963: 89, no. 49, repro.

1965

National Gallery of Art. Summary Catalogue of European Paintings and Sculpture. Washington, 1965: 65, as Balthasar Coymans.

1966

Cairns, Huntington, and John Walker, eds. A Pageant of Painting from the National Gallery of Art. 2 vols. New York, 1966: 1: 216, color repro., as Balthasar Coymans.

1968

National Gallery of Art. European Paintings and Sculpture, Illustrations. Washington, 1968: 57, repro., as Balthasar Coymans.

1969

Taylor, Katrina V. H. "A note on the identity of a member of the Coymans family by Frans Hals." Report and Studies in the History of Art 3 (1969): 106-108, fig. 1.

1970

Slive, Seymour. Frans Hals. 3 vols. National Gallery of Art Kress Foundation Studies in the History of European Art. London, 1970–1974: 1(1970):160, 185; 2(1970):pls. 253, 255; 3(1974):85-86, no. 166.

1972

Grimm, Claus. Frans Hals: Entwicklung, Werkanalyse, Gesamtkatolog. Berlin, 1972: 17, no. 130, figs. 145, 148.

1974

Montagni, E.C. L’opera completa di Frans Hals. Classici dell’Arte. Milan, 1974: 104, no. 167, repro., color repro. 51, and cover.

1975

European Paintings: An Illustrated Summary Catalogue. National Gallery of Art, Washington, 1975: 170, repro., as Balthasar Coymans.

Walker, John. National Gallery of Art, Washington. New York, 1975: 266-267, no. 349, repro.

1976

Montagni, E.C. Tout l'oeuvre peint de Frans Hals. Translated by Simone Darses. Les classiques de l'art. Paris, 1976: no. 167, repro.

1978

Haverkamp-Begemann, Egbert, ed. The Netherlands and the German-speaking countries, fifteenth-nineteenth centuries. Wadsworth Atheneum paintings catalogue 1. Hartford, 1978: 148.

1981

Baard, H. P. Frans Hals. New York, 1981: fig. 66.

1984

Walker, John. National Gallery of Art, Washington. Rev. ed. New York, 1984: 266, no. 343, color repro.

1985

Pelfrey, Robert H., and Mary Hall-Pelfrey. Art and Mass Media. New York, 1985: 98, repro.

European Paintings: An Illustrated Catalogue. National Gallery of Art, Washington, 1985: 196, repro.

1986

Sutton, Peter C. A Guide to Dutch Art in America. Grand Rapids and Kampen, 1986: 308, fig. 460.

1989

Slive, Seymour. Frans Hals. Exh. cat. National Gallery of Art, Washington; Royal Academy of Arts, London; Frans Halsmuseum, Haarlem. London, 1989: no. 61.

1990

Grimm, Claus. Frans Hals: The Complete Work. Translated by Jürgen Riehle. New York, 1990: 95, color fig. 15a, 186, color fig. 66, 193-194, 288, no. 127, repro.

1995

Wheelock, Arthur K., Jr. Dutch Paintings of the Seventeenth Century. The Collections of the National Gallery of Art Systematic Catalogue. Washington, 1995: 76-79, color repro. 77.

1996

Tansey, Richard G. and Fred S. Kleiner. Gardner's Art Through the Ages. 10th ed. Fort Worth, 1996: 855, color fig. 24.45.

2000

Weller, Dennis P. Like Father, Like Son? Portraits by Frans Hals and Jan Hals. Exh. cat. North Carolina Museum of Art, Raleigh, 2000: pl. 1.

2002

Beyer, Andreas. Das Porträt in der Malerei. Munich, 2002: 199-200, repro.

Dehne, Bernd, Helmuth Kern, and Erika Kern. Mensch, Kunst!. Basisreihe Kunst 4. Leipzig, 2002: 118, repro.

2003

Atkins, Christopher. "Frans Hals's Virtuoso Brushwork." Nederlands Kunsthistorisch Jaarboek (2003): 296, repro.

2004

Hand, John Oliver. National Gallery of Art: Master Paintings from the Collection. Washington and New York, 2004: 188, no. 148, color repro.

2005

Duffy-Zeballos, Lisa. "Frans Hals' Willem Coymans." Archives of Facial Plastic Surgery 7, no. 2 (March/April 2005): 152-153, color repro.

2007

Ekkart, Rudolf E.O., and Quentin Buvelot. Dutch portraits: the age of Rembrandt and Frans Hals. Translated by Beverly Jackson. Exh. cat. National Gallery, London; Royal Picture Gallery Mauritshuis, The Hague. London, 2007: 130-131, no. 24, repro.

2008

Buvelot, Quentin. "El retrato holandés." Numen 2 (2008): 11-12, repro.

2012

Atkins, Christopher D.M. The Signature Style of Frans Hals: Painting, Subjectivity, and the Market in Early Modernity. Amsterdam, 2012: 105-106, 292, color fig. 71.

2013

Bennett, Shelly M. _ The Art of Weath: The Huntingtons in the Gilded Age_. San Marino, 2013: 156, 161-161, 163, 177, 267-268, 270, color fig. 3.24.

Inscriptions

center right: AETA SVAE.22 (second 2 has been changed to a 6) / 1645 [1]

[1] The second numeral of the sitter’s age has been changed to a six. Above the inscription is the sitter’s coat of arms, consisting of three black cows’ heads on a gold field.

Wikidata ID

Q18010001