Ranuccio Farnese

1541-1542

Titian

Painter, Venetian, 1488/1490 - 1576

Ranuccio Farnese was 11 years old when Titian began to paint his portrait. Adult responsibility came to Ranuccio when he was still a child, as Titian brilliantly conveyed through the cloak of office, too large and heavy, sliding off the boy’s small shoulders.

When this painting was commissioned, Ranuccio had been sent to Venice by his grandfather, Pope Paul III, to become prior of an important property belonging to the Knights of Malta. A member of the powerful and aristocratic Farnese family, Ranuccio went on to an illustrious ecclesiastical career. He was made archbishop of Naples at the age of 14; by the time he was 19, he was patriarch of Constantinople and archbishop of Ravenna. He became archbishop of Milan in 1564, shortly before dying when he was only 35 years old.

Portraits by Titian were in great demand, distinguished as they were for their remarkable insight into character and their brilliant technique. Here, he limited his palette to black, white, and rose and enlivened the surface with light: the dull gleam rippling over the sleeves of the velvet cloak, the pattern flickering across the slashed doublet, and the changing reflections on the satin Maltese Cross.

Titian may have been motivated to approach this painting with particular care in the hope of securing papal patronage and work with the wealthy and influential Farneses. With the success of Ranuccio’s depiction, Titian was soon invited to paint a portrait of Paul III. His initial contacts with the papal family were followed by numerous additional Farnese commissions.

West Building Main Floor, Gallery 11

Artwork overview

-

Medium

oil on canvas

-

Credit Line

-

Dimensions

overall: 89.7 x 73.6 cm (35 5/16 x 29 in.)

framed: 123.83 × 108.9 × 9.53 cm (48 3/4 × 42 7/8 × 3 3/4 in.) -

Accession Number

1952.2.11

More About this Artwork

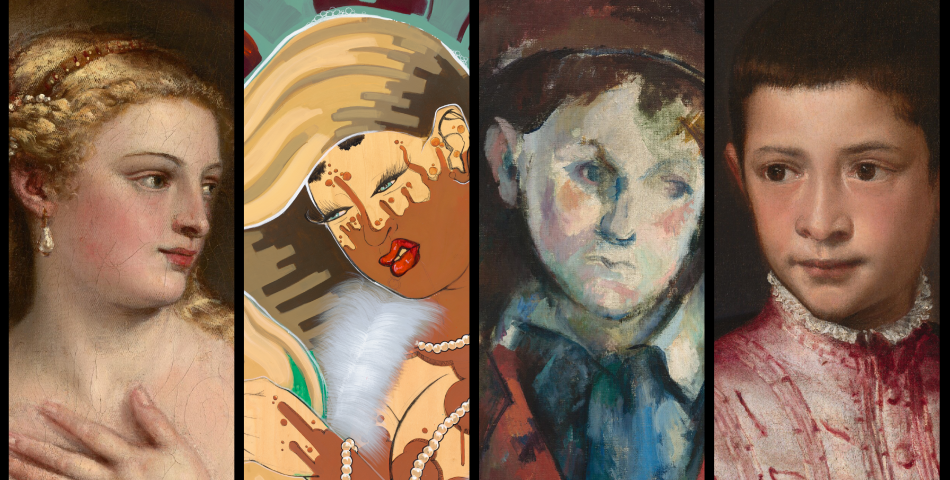

Interactive Article: Four Paintings Speak to Each Other Across Space and Time

See how Titian, Cezanne, and Rozeal. remix and reinterpret conventions for painting people.

Video: Titian's "Ranuccio Farnese" (ASL)

This video provides an ASL description of Titian's Ranuccio Farnese.

Artwork history & notes

Provenance

Farnese family, Parma, by 1644;[1] Farnese family, Palazzo del Giardino, Parma, by 1680;[2] Farnese family, Palazzo della Pilotta, Parma, by 1708;[3] by inheritance 1734 to the Bourbon collection, Naples;[4] Bourbon collection, Palazzo di Capodimonte, Naples, by 1765;[5] Bourbon collection, Palazzo Francavilla, Naples, by 1802;[6] Bourbon collection, Palazzo degli Studi, Naples, by 1816.[7] brought from Naples to London by Sir George Donaldson [1845-1925], London;[8] sold May 1880 to Sir John Charles Robinson [1824-1913], London; sold to Sir Francis Cook, 1st bt. [1817-1901], Doughty House, Richmond, Surrey, by 1885;[9] by inheritance to his son, Sir Frederick Lucas Cook, 2nd bt. [1844-1920], Doughty House; by inheritance to his son, Sir Herbert Frederick Cook, 3rd bt. [1868-1939], Doughty House; by inheritance to his son, Sir Francis Ferdinand Maurice Cook, 4th bt. [1907-1978], Doughty House, and Cothay Manor, Somerset; sold June or July 1947 to (Gualtiero Volterra, London) for (Count Alessandro Contini Bonacossi, Florence);[10] sold July 1948 to the Samuel H. Kress Foundation, New York;[11] gift 1952 to NGA.

[1] The portrait is recorded in an inventory of the pictures in the Palazzo Farnese drawn up in 1644 as follows: “4324. Un quadro in tela con cornice grande intagliata a basso relievo et indorata, con il ritratto del S.r cardinale S. Angelo giovanetto con l’habito di Malta, mano di Titiano.” See Bertrand Jestaz, ed., L’inventaire du Palais et des propriétés Farnèse à Rome en 1644, Vol. 3, Pt. 3: Le Palais Farnèse, Rome, 1994: 171. It is again recorded there in an inventory of 1653: see Giuseppe Bertini, La Galleria del Duca di Parma: Storia di una collezione, Bologna, 1987: 89.

[2] A Farnese inventory of 1680 describes the picture as follows: “Ritratto di un giovinetto vestito di rosso con sopraveste nera sopra della quale la croce di Cavaliere di Malta: tiene nella destra un guanto di Tiziano.” See: Amadeo Ronchini, “Delle relazioni di Tiziano coi Farnesi,” Atti e memorie delle RR Deputazioni di Storia Patria per le Provincie Modenesi e Parmensi 2 (1864): 145; Giuseppe Campori, Raccolta di cataloghi ed inventarii inediti, Modena, 1870: 239; Giuseppe Bertini, La Galleria del Duca di Parma: Storia di una collezione, Bologna, 1987: 89.

[3] For the Farnese inventory of 1708, see Giuseppe Bertini, La Galleria del Duca di Parma: Storia di una collezione, Bologna, 1987: 89. See also Descrizione per alfabetto di cento quadri de’ più famosi, e dipinti da i più insigni pittori del modo, che si osservano nella Galleria Farnese di Parma . . ., Parma[?], 1725: 46.

[4] The Farnese collection was transferred to Naples in 1734, probably initially to the Palazzo Reale, when it was inherited by Charles of Bourbon, king of Naples.

[5] Jérôme de Lalande, Voyage d’un français en Italie fait dans les années 1765 et 1766, 8 vols., Paris, 1769: 6:174; see also Giuseppe Sigismondo, Descrizione della città di Napoli e suoi borghi, 3 vols., Naples, 1788-1789: 3(1789):48. As pointed out by M. Utili (I Farnese: Arte e collezionismo, eds. Lucia Fornari Schianchi and Nicola Spinosa, exh. cat. Palazzo Ducale, Colorno; Galleria Nazionale di Capodimonte, Naples; Haus der Kunst, Munich; Milan, 1995: 206), the picture was probably transferred from the Palazzo Reale to the Palazzo di Capodimonte as part of the reorganization of the royal collection undertaken by Padre Giovanni Maria della Torre between 1756 and 1764.

[6] A. Filangieri di Candida, “La galleria nazionale di Napoli,” Le gallerie nazionali iItaliane 5 (1902): 304, no. 34. As pointed out by M. Utili (see note 5), the picture is probably identical with a “ritratto di giovane di Tiziano,” carried off to Rome in 1799 by French troops, together with other pictures from the royal collection, but returned to Naples before 1802.

[7] According to the inventory compiled by Paterno in 1816, quoted by M. Utili (see note 5). The picture appears to have left the Bourbon collection soon afterwards.

[8] According to Tancred Borenius, Sir Francis Cook acquired the painting through Sir George Donaldson. See: Tancred Borenius, A Catalogue of the Paintings at Doughty House, Richmond, and Elsewhere in the Collection of Sir Frederick Cook Bt.: Italian Schools. Vol. I, Pt. 2, ed. Herbert Cook, London, 1913: 170.

[9] According to Robinson's account book (Ashmolean Museum, Oxford; copy of relevant page in NGA curatorial files). Robinson, in “The Gallery of Pictures of Old Masters, formed by Francis Cook, Esq., of Richmond,” The Art Journal (1885): 136, records the picture in the Cook collection, and reports that it had been “brought to England a few years ago by an Italian gentleman from Naples.”

[10] See copy of correspondence in NGA curatorial files, from the Cook Collection Archive in care of John Somerville, England. Volterra was Contini Bonacossi's agent in London. For the formation and dispersal of the Cook collection, see Elon Danziger, “The Cook Collection, Its Founder and Its Inheritors,” The Burlington Magazine 146 (2004): 444–458.

[11] The Kress Foundation made an offer to Contini Bonacossi on 7 June 1948 for a group of twenty-eight paintings, including Titian's "Portrait of a Boy;" the offer was accepted on 11 July 1948 (see copies of correspondence in NGA curatorial files, see also The Kress Collection Digital Archive, https://kress.nga.gov/Detail/objects/1760.).

Associated Names

Exhibition History

1976

Zapadnoevropeiskaia i Amerikanskaia zhivopis is muzeev ssha [West European and American Painting from the Museums of USA], State Hermitage Museum, Leningrad; State Pushkin Museum, Moscow; State Museums, Kiev and Minsk, 1976, unpaginated and unnumbered catalogue.

1983

The Genius of Venice 1500-1600, Royal Academy of Arts, London, 1983-1984, no. 121, repro.

1990

Tiziano [NGA title: Titian: Prince of Painters], Palazzo Ducale, Venice; National Gallery of Art, Washington, 1990-1991, no. 33, repro.

1994

A Gift to America: Masterpieces of European Painting from the Samuel H. Kress Collection, four venues, 1994-1995, no. 2, repro. (shown only at first two venues: North Carolina Museum of Art, Raleigh, and Museum of Fine Arts, Houston).

1995

I Farnese: Arte e Collezionismo, Palazzo Ducale di Colorno, Parma; Haus der Kunst, Munich; Galleria Nazionale di Capodimonte, Naples, 1995-1996, no. 26, repro. (shown only in Munich and Naples).

2003

Titian, The National Gallery, London; Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid, 2003, no. 25 (English catalogue), no. 22 (Spanish catalogue), repros.

2009

Titian, Tintoretto, Veronese: Rivals in Renaissance Venice, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; Musée du Louvre, Paris, 2009-2010, no. 42 (English catalogue), no. 43 (French catalogue), repros.

2013

Tiziano, Scuderie del Quirinale, Rome, 2013, no. 22, repro.

2015

Loan for display with permanent collection, Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, Hartford, 2015.

2021

Remember Me: Renaissance Portraits, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, 2021, fig. 37, repro.

Bibliography

1725

Descrizione per Alfabetto di cento Quadri de’ più famosi, e dipinti da i più insigni pittori del modo, che si osservano nella Galleria Farnese di Parma... Parma[?], 1725: 46.

1769

La Lande, Jérôme de. Voyage d’un français en Italie fait dans les années 1765 et 1766. 8 vols. Paris, 1769: 6:174.

1788

Sigismondo, Giuseppe. Descrizione della città di Napoli e suoi borghi. 3 vols. Naples, 1788-1789: 3(1789):48.

1864

Ronchini, Amadeo. “Delle relazioni di Tiziano coi Farnesi.” Atti e Memorie delle RR Deputazioni di Storia Patria per le Provincie Modenesi e Parmensi 2 (1864):129-130, 145.

1870

Campori, Giuseppe. Raccolta di Cataloghi ed Inventarii Inediti. Modena, 1870: 239.

1877

Crowe, Joseph Archer, and Giovanni Battista Cavalcaselle. Titian, His Life and Times. 2 vols. London, 1877: 2:75-79.

1885

Robinson, John Charles. “The Gallery of Pictures of Old Masters, formed by Francis Cook, Esq., of Richmond.” The Art Journal (1885): 134, 136.

1902

Cust, Lionel. A Description of the Sketch-book by Sir Anthony Van Dyck. London, 1902: 22-23.

Filangieri di Candida, A. “La galleria nazionale di Napoli.” Le Gallerie Nazionali Italiane 5 (1902): 216, 229, 269, 275.

1903

Cook, Francis. Abridged Catalogue of the Pictures at Doughty House, Richmond, Belonging to Sir Frederick Cook, Bart., M.P., Visconde de Monserrate. London, 1903: 20.

1904

Gronau, Georg. Titian. London, 1904: 133.

1905

Cook, Herbert. “La collection de Sir Frederick Cook, Visconde de Monserrate.” Les Arts no. 44 (August 1905): 5-6.

Reinach, Salomon. Répertoire de peintures du moyen âge et de la Renaissance (1280-1580). 6 vols. Paris, 1905-1923: 6(1923):245.

1906

Gronau, Georg. “Zwei Tizianische Bildnisse der Berliner Galerie.” Jahrbuch der Königlich Preussischen Kunstsammlungen 27 (1906): 3-7.

1907

Fischel, Oskar. Tizian: Des Meisters Gemälde. 3rd ed. Stuttgart and Leipzig, 1907: 99, 236.

1910

Ricketts, Charles. Titian. London, 1910: 107 n. 1.

1913

Borenius, Tancred. A Catalogue of the Paintings at Doughty House, Richmond, and Elsewhere in the Collection of Sir Frederick Cook Bt. Italian Schools. Vol. I, Pt. 2. Edited by Herbert Cook. London, 1913: 170.

1921

Mayer, August L. “Fulvio Orsini, ein Gönner des jungen Greco.” Zeitschrift für Bildende Kunst 32 (1921): 119.

1930

Waterhouse, Ellis K. "El Greco's Italian Period." Art Studies 8 (1930): 70-71, 85.

1932

Berenson, Bernard. Italian Pictures of the Renaissance: A List of the Principal Artists and Their Works with an Index of Places. Oxford, 1932: 574.

Brockwell, Maurice W. Abridged Catalogue of the Pictures at Doughty House, Richmond, Surrey, in the Collection of Sir Herbert Cook. London, 1932: 68-69.

1933

Suida, Wilhelm. Tizian. Zürich and Leipzig, 1933: 89-90, 103, 165.

1936

Berenson, Bernard. Pitture italiane del rinascimento: catalogo dei principali artisti e delle loro opere con un indice dei luoghi. Translated by Emilio Cecchi. Milan, 1936: 494.

Tietze, Hans. Tizian: Leben und Werk. 2 vols. Vienna, 1936: 1:174, 307.

1939

Kelly, Francis M. “Note on an Italian Portrait at Doughty House.” The Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs 75 (August 1939): 75-77.

1940

Adriani, Gert. Anton Van Dyck, Italienisches Skizzenbuch. Vienna, 1940: 69.

1944

Pallucchini, Rodolfo. La pittura veneziana del Cinquecento. 2 vols. Novara, 1944: 1:xxii.

1950

Tietze, Hans. Titian. The Paintings and Drawings. London, 1950: 39, 391.

1951

Paintings and Sculpture from the Kress Collection Acquired by the Samuel H. Kress Foundation 1945-1951. Introduction by John Walker, text by William E. Suida. National Gallery of Art, Washington, 1951: 114, no. 47, repro.

King, Marian. Portfolio Number 3. National Gallery of Art, Washington, 1951: no. 3, color repro.

1952

Suida, Wilhelm. “Miscellanea Tizianesca.” Arte Veneta 6 (1952): 38-40.

1953

Pallucchini, Rodolfo. Tiziano. Lezioni di storia dell’arte. 2 vols. Bologna, 1953-1954: 1:209, 212; 2:11, 16.

1955

Dell’Acqua, Gian Alberto. Tiziano. Milan, 1955: 123.

1957

Berenson, Bernard. Italian Pictures of the Renaissance. Venetian School. 2 vols. London, 1957: 1:192.

1959

Shapley, Fern Rusk. Early Italian Painting in the National Gallery of Art. Washington, D.C., 1959 (Booklet Number Three in Ten Schools of Painting in the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.): pl. 75.

Kress 1957, 191, repro.

Morassi, Antonio. “Titian.” In Encyclopedia of World Art. 17+ vols. London, 1959+: 14(1967):col. 143.

1960

Valcanover, Francesco. Tutta la pittura di Tiziano. 2 vols. Milan, 1960: 1:73.

Fragnito, Gigliola. “Ranuccio Franese.” In Dizionario biografico degli italiani. Edited by Alberto Maria Ghisalberti. 82+ vols. Rome, 1960+: 45(1995):150.

1961

Walker, John, Guy Emerson, and Charles Seymour. Art Treasures for America: An Anthology of Paintings & Sculpture in the Samuel H. Kress Collection. London, 1961: 120, repro. pl. 113, 115.

1962

Cairns, Huntington, and John Walker, eds. Treasures from the National Gallery of Art. New York, 1962: 32, color repro.

Neugass, Fritz. "Die Auflösung der Sammlung Kress." Die Weltkunst 32 (1 January, 1962): 4.

Wethey, Harold E. El Greco and His School. 2 vols. Princeton, 1962: 2:202.

1963

Walker, John. National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. New York, 1963 (reprinted 1964 in French, German, and Spanish): 307, repro.

1964

Morassi, Antonio. Titian. Greenwich, CT, 1964: 38.

1965

Summary Catalogue of European Paintings and Sculpture. National Gallery of Art, Washington, 1965: 130.

1966

Cairns, Huntington, and John Walker, eds. A Pageant of Painting from the National Gallery of Art. 2 vols. New York, 1966: 1:178-179, color repro.

Pope-Hennessy, John. The Portrait in the Renaissance. London and New York, 1966: 279-280, 326.

1967

Fabbro, Celso. “Tiziano, i Farnese e l’abbazia di San Pietro in Colle nel Cenedese.” Archivio Storico di Belluno, Feltre e Cadore 38 (1967): 3.

1968

National Gallery of Art. European Paintings and Sculpture, Illustrations. Washington, 1968: 116, repro.

Shapley, Fern Rusk. Paintings from the Samuel H. Kress Collection: Italian Schools, XV-XVI Century. London, 1968: 182-183, fig. 428-429.

Ballarin, Alessandro. “Pittura veneziana nei Musei di Budapest, Dresda, Praga e Varsavia.” Arte Veneta 22 (1968): 247.

1969

Matteoli, Anna. “La ritrattistica del Bronzino nel ‘Limbo.’” Commentari 20, no. 4 (1969): 303-304.

Pallucchini, Rodolfo. Tiziano. 2 vols. Florence, 1969: 1:99, 107, 277.

Valcanover, Francesco. L’opera completa di Tiziano. Milan, 1969: 112-113.

Wethey, Harold. The Paintings of Titian. 3 vols. London, 1969-1975: 2(1971):28, 98-99.

1972

Fredericksen, Burton B., and Federico Zeri. Census of Pre-Nineteenth Century Italian Paintings in North American Public Collections. Cambridge, Mass., 1972: 203, 513, 647.

1975

European Paintings: An Illustrated Summary Catalogue. National Gallery of Art, Washington, 1975: 346, repro.

1976

Gallego, Julian. “El retrato en Tiziano.” Goya 135 (1976): 171.

Krsek, Ivo. Tizian. Prague, 1976: 65.

Pozza, Neri. Tiziano. Milan, 1976: 251.

Rizzati, Maria Luisa. Tiziano. Milan, 1976: 93.

1977

Pallucchini, Rodolfo. Profilo di Tiziano. Florence, 1977: 39.

1978

Rosand, David. Titian. New York, 1978: 114.

1979

Shapley, Fern Rusk. Catalogue of the Italian Paintings. 2 vols. National Gallery of Art, Washington, 1979: 1:483-485; 2:pl. 344.

1980

Meller, Peter. “Il lessico ritrattistico di Tiziano.” In Tiziano e Venezia: Convegno internazionale di studi (1976). Vicenza, 1980: 332.

Pallucchini, Rodolfo. “Tiziano e la problematica del Manierismo.” In Tiziano e Venezia: Convegno internazionale di studi (1976). Vicenza, 1980: 401.

1983

Ramsden, E. H. “Come, take this lute”: A Quest for Identities in Italian Renaissance Portraiture. Salisbury, 1983: 64, 193.

Martineau, Jane, and Charles Hope. The Genius of Venice, 1500-1600. Exh. cat. Royal Academy of Arts, London, 1983: 225.

1984

Walker, John. National Gallery of Art, Washington. Rev. ed. New York, 1984: 206, no. 248, color repro.

1985

European Paintings: An Illustrated Catalogue. National Gallery of Art, Washington, 1985: 396, repro.

1986

Gemäldegalerie Berlin: Gesamtverzeichnis der Gemälde. Berlin, 1986: 75.

1987

Wethey, Harold E. Titian and His Drawings, with Reference to Giorgione and Some Close Contemporaries. Princeton, 1987: 83 n.80, 98 n.80.

Bertini, Giuseppe. La Galleria del Duca di Parma. Storia di una Collezione. Bologna, 1987: 41, 57, 62, 89.

1989

Freedman, Luba. “Titian’s Portrait of Clarissa Strozzi: The State Portrait of a Child.” Jahrbuch der Berliner Museen 39 (1989): 177.

1990

Campbell, Lorne. Renaissance Portraits: European Portrait-Painting in the 14th, 15th, and 16th Centuries. New Haven, 1990: 178-179, 181, color fig. 194,195.

Titian, Prince of Painters. Exh. cat. Palazzo Ducale, Venice; National Gallery of Art, Washington. Venice, 1990: 244.

Zapperi, Roberto. Tiziano, Paolo III e i suoi nipoti: Nepotismo e ritratto di stato. Turin, 1990: 27.

1991

Zapperi, Roberto. “Tiziano e i Farnese: Aspetti economici del rapporto di committenza.” Bolletino d’arte 76 (1991): 39.

1992

National Gallery of Art, Washington. National Gallery of Art, Washington, 1992: 101, repro.

Robertson, Clare. Il Gran Cardinale: Alessandro Farnese, Patron of the Arts. New Haven and London, 1992: 69-70.

1993

Oberhuber, Konrad. “La mostra di Tiziano a Venezia.” Arte Veneta 44 (1993): 79.

1994

Jaffe, Michael. "On Some Portraits Painted by Van Dyck in Italy, Mainly in Genoa." Studies in the History of Art 46 (1994): 141-142.

Jestaz, Bertrand, ed. L’Inventaire du Palais et des Propriétés Farnèse à Rome en 1644, Vol. 3, Pt. 3: Le Palais Farnèse. Rome, 1994: 171.

1995

Tuohy, Thomas. “The Farnese: What a Family.” Apollo 142, no. 403 (September 1995): 64.

Fornari Schianchi, Lucia, and Nicola Spinosa, eds. I Farnese: Arte e collezionismo. Exh. cat. Palazzo Ducale, Colorno; Galleria Nazionale di Capodimonte, Naples; Haus der Kunst, Munich. Milan, 1995: 203-206.

1998

Kaminsky, Marion. Titian. Cologne, 1998: 76-77.

1999

Cole, Bruce. Titian and Venetian Painting, 1450-1590. Boulder, 1999: 110-112.

Valcanover, Francesco. Tiziano: I suoi pennelli sempre partorirono espressioni di vita. Florence, 1999: 43, 267.

2001

Pedrocco, Filippo. Titian: The Complete Paintings. New York, 2001: 50, 179.

2003

Jaffé, David, ed. Titian. Exh. cat. The National Gallery, London, 2003: 136.

Falomir, Miguel, ed. Tiziano. Exh. cat. Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid, 2003: 192, 370-371.

Fletcher, Jennifer. “Titian as a Painter of Portraits.” In Titian. Edited by David Jaffé. Exh. cat. The National Gallery, London, 2003: 39-40.

2004

Danziger, Elon. "The Cook Collection: Its Founder and Its Inheritors." The Burlington Magazine 146, no. 1216 (July 2004): 457.

Hand, John Oliver. National Gallery of Art: Master Paintings from the Collection. Washington and New York, 2004: 102-103, no. 78, color repro.

2006

Fletcher, Jennifer. “‘La sembianza vera.’ I ritratti di Tiziano.” In Tiziano e il ritratto di corte da Raffaello ai Carracci. Edited by Nicola Spinosa. Exh. cat. Museo Nazionale di Capodimonte, Naples, 2006: 40.

Wolf, Norbert. Tizian. Munich, 2006: 67.

Zapperi, Roberto. “Tiziano e i Farnese.” In Tiziano e il ritratto di corte da Raffaello ai Carracci. Edited by Nicola Spinosa. Exh. cat. Museo Nazionale di Capodimonte, Naples, 2006: 51.

2007

Humfrey, Peter. Titian: The Complete Paintings. Ghent and New York, 2007: 187.

Humfrey, Peter. Titian. London, 2007: 138.

Romani, Vittoria. Tiziano e il tardo rinascimento a Venezia: Jacopo Bassano, Jacopo Tintoretto, Paolo Veronese. Florence, 2007: 114, 135.

2008

Fletcher, Jennifer. “El retrato renacentista: Funciones, usos y exhibición.” In El retrato del Renacimiento. Edited by Miguel Falomir. Exh cat. Museo del Nacional Prado, Madrid, 2008: 76.

2009

Ilchman, Frederick, et al. Titian, Tintoretto, Veronese: Rivals in Renaissance Venice. Exh. cat. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; Musée du Louvre, Paris. Boston, 2009: 216-219.

Ilchman, Frederick, et al. Titien, Tintoret, Véronèse: Rivalités à Venise. Exh. cat., Musée du Louvre, Paris, 2009: 276.

2011

Biferali, Frabrizio. Tiziano: Il genio e il potere. Rome, 2011: 161.

2012

Gentili, Augusto. Tiziano. Milan, 2012: 210-212.

Hale, Sheila. Titian: His Life. London, 2012: 437.

2013

Smith, Zadie. "Man vs. Corpse." New York Review of Books 60, no. 19 (December 5, 2013): 16, color fig.

Villa, Giovanni C.F., ed. Tiziano. Exh. cat., Scuderie del Quirinale, Rome. Milan, 2013: 178-181.

Marinelli, Sergio. “Pietro Bembo nella storia della pittura.” In Pietro Bembo e le arti. Edited by Guido Beltramini, Howard Burns, and Davide Gasparotto. Venice, 2013: 476-477.

Avery-Quash, Susanna. “Titian at the National Gallery, London: An Unchanging Reputation?” In The Reception of Titian in Britain: From Reynolds to Ruskin. Edited by Peter Humfrey. Turnhout, 2013: 224.

2014

Bouvrande, Isabelle. Le Coloris Vénitien à la Renaissance. Autour de Titien. Paris, 2014: 167-169.

2015

Lacourture, Fabien. “’You Will Be a Man, My Son’: Signs of Masculinity and Virility in Italian Renaissance Paintings of Boys.” In The Early Modern Child in Art and History. Edited by Matthew Knox Averett. The Body, Gender and Culture 18. Oxford and New York, 2015: 108-110, fig. 6.5.

2025

Healy, Rachel. "Three men and an abbey:the Cornaro triple portrait." Renaissance Studies (21 April, 2025): 20, fig. 9. https://doi.org/10.1111/rest.12989.

Inscriptions

center right: TITIANVS / .f.

Wikidata ID

Q12146958