Venus with a Mirror

c. 1555

Titian

Painter, Venetian, 1488/1490 - 1576

Titian’s goddess of love and beauty conjures the sense of touch. Observing her flushed cheek, one can almost feel its warmth. The textures of flesh, jewels, fabric, and fur are exquisitely detailed. In the mirror a cupid holds up to her, she appears not to view herself, but perhaps someone gazing at her.

This is considered the finest surviving version of a composition executed in at least 30 variants by Titian and his workshop. It remained in the artist’s possession until his death, more than 20 years after he painted it. The reason Titian retained a painting of such high quality for so long is uncertain, but this Venus may have been a source of inspiration to those who worked for or visited the artist. For members of the workshop, she may have served as a model for replication, and the painting may have prompted visitors to order similar pictures for themselves.

When he painted this work, Titian reused a canvas that once depicted two figures in three-quarter-length view standing side by side. He rotated the canvas 90 degrees, and it appears that he left exposed the jacket of the male figure in the underlying composition to create the luxurious fur-lined red velvet that now wraps around Venus’s hip.

West Building Main Floor, Gallery 11

Artwork overview

-

Medium

oil on canvas

-

Credit Line

-

Dimensions

overall: 124.5 x 105.5 cm (49 x 41 9/16 in.)

framed: 157.48 x 139.07 x 10.8 cm (62 x 54 3/4 x 4 1/4 in.) -

Accession Number

1937.1.34

More About this Artwork

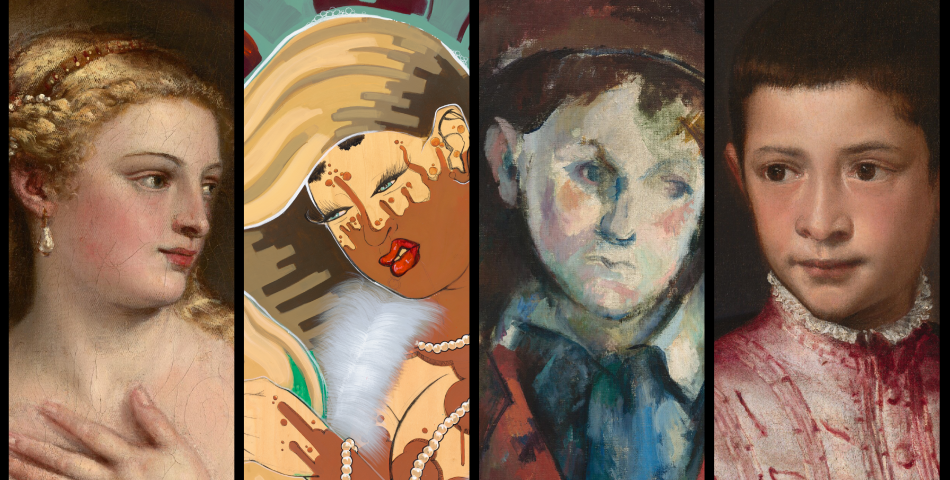

Interactive Article: Four Paintings Speak to Each Other Across Space and Time

See how Titian, Cezanne, and Rozeal. remix and reinterpret conventions for painting people.

Artwork history & notes

Provenance

The artist [c. 1490-1576], Venice; by inheritance to his son, Pomponio Vecellio, Venice; sold 27 October 1581 with the contents of Titian's house to Cristoforo Barbarigo [1544-1614], Venice; by inheritance to his son, Andrea Barbarigo;[1] by inheritance in the Barbarigo family, Palazzo Barbarigo della Terrazza, Venice;[2] sold 1850 by the heirs of Giovanni di Alvise Barbarigo [d. 1843] to Czar Nicholas I of Russia [1796-1855], Saint Petersburg;[3] Imperial Hermitage Gallery, St. Petersburg;[4] purchased April 1931 through (Matthiesen Gallery, Berlin; P. & D. Colnaghi & Co., London; and M. Knoedler & Co., New York) by Andrew W. Mellon, Pittsburgh and Washington, D.C.; deeded 5 June 1931 to The A.W. Mellon Educational and Charitable Trust, Pittsburgh;[5] gift 1937 to NGA.

[1] See Giuseppe Cardorin, Dello amore ai veneziani di Tiziano Vecellio delle sue case in Cadore e in Venezia, Venice, 1833: 77, 98-101, quoting the purchase document of October 1581 and Barbarigo’s will of March 1600, in which the Venus is mentioned as one of four pictures by Titian left to his heirs. See also Simona Savini Branca, Il collezionismo veneziano del Seicento, Padua, 1965: 47, 65, 183-186; Charles Hope, Titian, London, 1980: 167; Herbert Siebenhüner, Der Palazzo Barbarigo della Terrazza in Venedig und seine Tizian-Sammlung, Munich, 1981: 28; Jaynie Anderson, “Titian’s Unfinished ‘Portrait of a Patrician Woman and Her Daughter’ from the Barbarigo Collection, Venice,” The Burlington Magazine 144 (2002): 671, 672, 676; Lionello Puppi, Su Tiziano, Milan, 2004: 77; Charles Hope, “Tizians Familie und die Zerstreuung seines Nachlasses,” in Der späte Tizian und die Sinnlichkeit der Malerei, ed. Sylvia Ferino-Pagden, exh. cat. Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna; Gallerie dell'Accademia, Venice, Vienna, 2007: 35 (English edition: “Titian’s Family and the Dispersal of His Estate,” in Late Titian and the Sensuality of Painting, Venice, 2008: 37).

[2] The picture is recorded in the Palazzo Barbarigo by Carlo Ridolfi, Le maraviglie dell’arte, overo Le vite de gl'illustri pittori veneti, e dello stato, ed. Detlev von Hadeln, 2 vols., Berlin, 1914–1924 (originally Venice, 1648): 1(1914):200 (“Gli Signori Barbarighi di San Polo possiedono . . . vna Venere sino à ginocchi, che si vagheggia nello specchio con due Amori”); Marco Boschini, La carta del navegar pitoresco (1660), ed. Anna Pallucchini, Venice, 1966 (originally 1660): 664; Francesco Sansovino, Venetia città nobilissima et singolare (1581) . . . Con aggiunta di tutte le cose notabili della stessa città, fatte et occorse dall’anno 1580 fino al presente 1663 da D. Giustiniano Martinioni, Venice, 1663: 374; Arthur Young, Travels in France & Italy during the Years 1787, 1788, and 1789, London, 1915: 255; Abraham Hume, Notices of the Life and Works of Titian, London, 1829: 55, xxxix; Giuseppe Cadorin, Dello amore ai Veneziani di Tiziano Vecellio, Venice, 1833: 77, 98–101; and Gian Carlo Bevilacqua, Insigne Pinacoteca della nobile veneta famiglia barbarigo della Terrazza, Venice, 1845: 65, 67.

[3] Cesare Augusto Levi, Le collezioni veneziane d’arte e d’antichità dal secolo XIV ai nostri giorni, Venice, 1900: 281–289; Herbert Siebenhüner, Der Palazzo Barbarigo della Terrazza in Venedig und seine Tizian-Sammlung, Munich, 1981: 26.

[4] Eremitage Impérial: Catalogue de la Galerie des Tableaux, Saint Petersburg, 1863: 26, no. 99, and subsequent Hermitage catalogues.

[5] Mellon purchase date and date deeded to Mellon Trust is according to Mellon collection records in NGA curatorial files and David Finley's notebook (donated to the National Gallery of Art in 1977, now in the Gallery Archives).

Associated Names

Exhibition History

1979

The Golden Century of Venetian Painting, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 1979-1980, no. 21, repro.

1990

Tiziano [NGA title: Titian: Prince of Painters], Palazzo Ducale, Venice; National Gallery of Art, Washington, 1990-1991, no. 51, repro.

1993

Le siècle de Titien: L'âge d'or de la peinture à Venise, Galeries du Grand Palais, Paris, 1993, no. 178, repro., as Vénus à sa toilette.

2002

Tiziano / Rubens. Venus ante el espejo, Fundación Colección Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid, 2002-2003, no. 2, repro.

Nicholas I and the New Hermitage, The State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia, 2002, unnumbered catalogue.

2007

Der späte Tizian und die Sinnlichkeit der Malerei / Tiziano maturo e la sensualità della pittura, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna; Gallerie dell'Accademia, Venice, 2007-2008, no. 2.5, repro. (shown only in Vienna).

2009

Titian, Tintoretto, Veronese: Rivals in Renaissance Venice, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; Musée du Louvre, Paris, 2009-2010, no. 30 (no. 29 in French catalogue), repro.

Bibliography

1663

Sansovino, Francesco. Venetia città nobilissima et singolare (1581)...Con aggiunta di tutte le cose notabili della stessa città, fatte et occorse dall’anno 1580 fino al presente 1663 da D. Giustiniano Martinioni. Venice, 1663: 374.

1829

Hume, Abraham. Notices of the Life and Works of Titian. London, 1829: 55, xxxix.

1833

Cadorin, Giuseppe. Dello Amore ai Veneziani di Tiziano Vecellio. Venice, 1833: 77, 98-101.

1845

Bevilacqua, Gian Carlo. Insigne Pinacoteca della nobile veneta famiglia barbarigo della Terrazza. Venice, 1845

1863

Eremitage Impérial. Catalogue de la Galerie des Tableaux. St Petersburg, 1863: 26 no. 99.

1864

Viardot, Louis. “Le Musée de l’Ermitage a Saint Pétersbourg et son nouveau catalogue.” Gazette des Beaux-Arts 17 (1864): 322.

Waagen, Gustav Friedrich. Die Gemäldesammlung in der kaiserlichen Ermitage zu St. Petersburg nebst Bemerkungen über andere dortige Kunstsammlungen. Munich, 1864: 62.

1869

Eremitage Impérial. Catalogue de la Galerie des Tableaux. Les Écoles d’Italie et d’Espagne. St. Petersburg, 1869: 42-43.

1877

Crowe, Joseph Archer, and Giovanni Battista Cavalcaselle. Titian, His Life and Times. 2 vols. London, 1877: 2:334-336.

1886

Lafenestre, Georges. La vie et l’oeuvre de Titien. Paris, 1886: 234.

1891

Brüiningk, E., and Andrei Somof. Eremitage Impérial. Catalogue de la Galerie des Tableaux. Les Écoles d’Italie et d’Espagne. St Petersburg, 1891: 161-162 no. 99.

1897

Knackfuss, Hermann. Tizian. Bielefeld and Leipzig, 1897: 140.

Stillman, W. J. Venus and Apollo in Painting and Sculpture. London, 1897: 36.

1898

Phillips, Claude. The Later Work of Titian. London, 1898: 77, 90.

1899

Phillips, Claude. “The Picture Gallery of the Hermitage.” The North American Review 169, no. 4 (October 1899): 469.

1900

Gronau, Georg. Tizian. Berlin, 1900: 191.

Levi, Cesare Augusto. Le collezioni veneziane d’arte e d’antichità dal secolo XIV ai nostri giorni. Venice, 1900: 288.

1901

Venturi, Adolfo. Storia dell’arte italiana. 11 vols. Milan, 1901-1940: 9, part 3(1928):327-331.

1904

Fischel, Oskar. Tizian: Des Meisters Gemälde. Stuttgart [u.a.], 1904: 147.

Gronau, Georg. Titian. London, 1904: 197-198, 301.

1905

Miles, Henry. The Later Work of Titian. London, 1905: xxvii, 45.

Reinach, Salomon. Répertoire de peintures du moyen âge et de la Renaissance (1280-1580). 6 vols. Paris, 1905-1923: 6(1923):273.

1906

Kilényi, Hugo von. Ein wiedergefundenes Bild des Tizian. Budapest, 1906.

1907

Schmidt, James. “Les Toilette de Vénus du Titien: L’orignal et les répliques.” Starye Gody pt. 1 (1907): 216–222.

Hetzer, Theodor. “Vecellio, Tiziano.” In Allgemeines Lexikon der bildenden Künstler von der Antike bis zur Gegenwart. Edited by Ulrich Thieme, Felix Becker, and Hans Vollmer. 37 vols. Leipzig, 1907-1950: 34(1939):166.

1909

Wrangell, Baron Nicolas. Les Chefs-d'Oeuvre de la Galérie de Tableaux de l'Hermitage Impérial à St-Pétersbourg. London, 1909: vii, repro. 21.

Lafenestre, Georges. La vie et l’oeuvre de Titien. Rev. ed. Paris, 1909: 227, 278, 296-297.

1910

Ricketts, Charles. Titian. London, 1910: 122.

1911

Benois, Alexandre. Guide to the Hermitage Gallery (in Russian). St. Petersburg, 1911: 52-53.

1914

Ridolfi, Carlo. Le maraviglie dell’arte, overo Le vite de gl'illustri pittori veneti, e dello Stato (Venice, 1648). Edited by Detlev von Hadeln. 2 vols. Berlin, 1914-1924: 1(1914):200.

1915

Young, Arthur. Travels in France & Italy during the Years 1787, 1788 and 1789. London, 1915: 255.

1918

Basch, Victor. Titien. Paris, 1918: 214-216.

1919

Hourticq, Louis. La Jeunesse de Titien. Paris, 1919: 31.

1923

Weiner, Peter Paul von. Meisterwerke der Gemäldesammlung in der Eremitage zu Petrograd. Rev. ed. Munich, 1923: 11, 326.

1924

Bercken, Erich von der. “Some Unpublished Works by Tintoretto and Titian.” The Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs 44 (March 1924): 113.

1926

Venturi, Lionello. La Collezione Gualino. Turin and Rome, 1926: pl. 39.

1929

Poglayen-Neuwall, Stephan. “Eine tizianeske Toilette der Venus aus dem Cranach-Kreis.” Münchner Jahrbuch der Bildenden Kunst 6, no. 2 (1929): 167-199.

1932

Berenson, Bernard. Italian Pictures of the Renaissance: A List of the Principal Artists and Their Works with an Index of Places. Oxford, 1932: 571.

1933

Suida, Wilhelm. Tizian. Zürich and Leipzig, 1933: 116, 171.

1934

Poglayen-Neuwall, Stephan. “Titian’s Pictures of the Toilet of Venus and Their Copies.” The Art Bulletin 16 (1934): 358-384.

1935

Tietze, Hans. Meisterwerke europäischer Malerei in Amerika. Vienna, 1935: 87, repro. (English ed., Masterpieces of European Painting in America. New York, 1939: 88, repro.).

Hetzer, Theodor. Tizian: Geschichte seiner Farbe. Frankfurt-am-Main, 1935: 147, 163.

Mostra di Tiziano. Exh. cat. Palazzo Pesaro Papafava, Venice, 1935: 163.

1936

Tietze, Hans. Tizian: Leben und Werk. 2 vols. Vienna, 1936: 1:237, 314.

1937

Cortissoz, Royal. An Introduction to the Mellon Collection. Boston, 1937: repro. 8.

Jewell, Edward Alden. "Mellon's Gift." Magazine of Art 30, no. 2 (February 1937): 82.

1941

Preliminary Catalogue of Paintings and Sculpture. National Gallery of Art, Washington, 1941: 196, no. 34.

Wulff, Oskar. “Farbe, Licht und Schatten in Tizians Bildgestaltung.” Jahrbuch der preussischen Kunstsammlungen 62 (1941): 173, 194, 197, 199.

Stepanow, Giovanni. Tizian. Leipzig, 1941: xxxix.

1942

Book of Illustrations. National Gallery of Art, Washington, 1942: 239, repro. 199.

1944

Pallucchini, Rodolfo. La pittura veneziana del Cinquecento. 2 vols. Novara, 1944: 1:xxiv.

1946

Favorite Paintings from the National Gallery of Art Washington, D.C.. New York, 1946: 33-35, color repro.

Riggs, Arthur Stanley. Titian the Magnificent and the Venice of His Day. New York, 1946: 290, 324-326.

1947

Poglayen-Neuwall, Stephan. “The Venus of the Ca’ d’Oro and the Origin of the Chief Types of the Venus at the Mirror from the Workshop of Titian.” The Art Bulletin 29 (1947): 195-196.

1949

Paintings and Sculpture from the Mellon Collection. National Gallery of Art, Washington, 1949 (reprinted 1953 and 1958): 38, repro.

1950

Tietze, Hans. Titian. The Paintings and Drawings. London, 1950: 204 no. 218.

1951

Einstein, Lewis. Looking at Italian Pictures in the National Gallery of Art. Washington, 1951: 84-86, repro.

Hartlaub, Gustav F. Zauber des Spiegels: Geschichte und Bedeutung des Spiegels in der Kunst. Munich, 1951: 79-80, 107-108, 218.

1952

Cairns, Huntington, and John Walker, eds., Great Paintings from the National Gallery of Art. New York, 1952: 60, color repro.

Waterhouse, Ellis. “Paintings from Venice for Sevententh-Century England.” Italian Studies 7 (1952): 12.

1953

Pallucchini, Rodolfo. Tiziano. Lezioni di storia dell’arte. 2 vols. Bologna, 1953-1954: 2:63-64.

1955

Dell’Acqua, Gian Alberto. Tiziano. Milan, 1955: 127.

1956

Walker, John. National Gallery of Art, Washington. New York, 1956: 28, color repro.

1957

Shapley, Fern Rusk. Comparisons in Art: A Companion to the National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC. London, 1957 (reprinted 1959): pl. 47.

Berenson, Bernard. Italian Pictures of the Renaissance. Venetian School. 2 vols. London, 1957: 1:192.

1958

Tervarent, Guy de. Attributs et symboles dans l'art profane, 1450-1600. 3 vols. Geneva, 1958-1964: 1(1958):324.

1959

Morassi, Antonio. “Titian.” In Encyclopedia of World Art. 17+ vols. London, 1959+: 14(1967):col. 147.

1960

The National Gallery of Art and Its Collections. Foreword by Perry B. Cott and notes by Otto Stelzer. National Gallery of Art, Washington (undated, 1960s): 26, color repro. 12.

Shapley, Fern Rusk. Later Italian Painting in the National Gallery of Art. Washington, D.C., 1960 (Booklet Number Six in Ten Schools of Painting in the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.): 30, color repro.

Valcanover, Francesco. Tutta la pittura di Tiziano. 2 vols. Milan, 1960: 2:39-40.

1963

Walker, John. National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. New York, 1963 (reprinted 1964 in French, German, and Spanish): 148, repro.

Kennedy, Ruth Wedgwood. Novelty and Tradition in Titian’s Art. Northampton, Mass., 1963: 6, 20 n. 29.

1964

Savini Branca, Simona. Il collezionismo veneziano del Seicento. Padua, 1964: 186.

1965

Summary Catalogue of European Paintings and Sculpture. National Gallery of Art, Washington, 1965: 129.

1966

Cairns, Huntington, and John Walker, eds. A Pageant of Painting from the National Gallery of Art. 2 vols. New York, 1966: 1:172, color repro.

Walton, William. "Parnassus on Potomac." Art News 65 (March 1966): 38.

Boschini, Marco. La Carta del Navegar Pitoresco (1660). Edited by Anna Pallucchini. Venice, 1966: 664.

1968

National Gallery of Art. European Paintings and Sculpture, Illustrations. Washington, 1968: 116, repro.

Gandolfo, Giampaolo et al. National Gallery of Art, Washington. Great Museums of the World. New York, 1968: 46, 48-49, color repro.

1969

Pallucchini, Rodolfo. Tiziano. 2 vols. Florence, 1969: 1:143, 302.

Valcanover, Francesco. L’opera completa di Tiziano. Milan, 1969: 124-125 no. 384.

Wethey, Harold. The Paintings of Titian. 3 vols. London, 1969-1975: 3(1975):26, 67-70, 200-201.

1971

Freedberg, Sydney J. Painting in Italy 1500-1600. Harmondsworth, 1971, rev. ed. 1975: 508-509.

Pallucchini, Rodolfo. “Una nuova Pomona di Tiziano.” Pantheon 29 (1971): 114.

1972

Shapley, Fern Rusk. "Titian's Venus with a Mirror." Studies in the History of Art v.4 (1971-72):93-105, repro.

Fredericksen, Burton B., and Federico Zeri. Census of Pre-Nineteenth Century Italian Paintings in North American Public Collections. Cambridge, Mass., 1972: 203, 476, 645.

1973

Klesse, Brigitte. Katalog der italienischen, französischen and spanischen Gemälde bis 1800 im Wallraf-Richartz-Museum. Cologne, 1973: 131-135.

Moretti, Lino, ed. G. B. Cavalcaselle. Disegni da Antichi Maestri. Exh. cat. Fondazione Giorgio Cini, Venice. Vicenza, 1973: 113.

Finley, David Edward. A Standard of Excellence: Andrew W. Mellon Founds the National Gallery of Art at Washington. Washington, 1973: 22, 28 repro.

1974

Faldi, Italo. “Dipinti di figure dal rinascimento al neoclassicismo.” In L’Accademia Nazionale de San Luca. Rome, 1974: 96.

1975

European Paintings: An Illustrated Summary Catalogue. National Gallery of Art, Washington, 1975: 344, repro.

1976

Krsek, Ivo. Tizian. Prague, 1976: 69.

1977

Bialostocki, Jan. “Man and Mirror in Painting: Reality and Transience.” In Studies in Late Medieval and Renaissance Painting in Honor of Millard Meiss. Edited by Irving Lavin and John Plummer. New York, 1977: 70.

Fomichova, Tamara. “Lo sviluppo compositivo della Venere allo Speccio con due Amorini nell’opera di Tiziano e la copia dell’Eremitage.” Arte Veneta 31 (1977): 195-199.

Pallucchini, Rodolfo. Profilo di Tiziano. Florence, 1977: 46.

1978

Hadeln, Detlev von. Paolo Veronese. Florence, 1978: 84.

Rosand, David. Titian. New York, 1978: 33-34.

1979

Shapley, Fern Rusk. Catalogue of the Italian Paintings. 2 vols. Washington, 1979: 1:476-480; 2:pl. 341, 341A,B,C.

Watson, Ross. The National Gallery of Art, Washington. New York, 1979: 39, pl. 24.

Pignatti, Terisio. Golden Century of Venetian Painting. Exh. cat. Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles, 1979: 76-77.

1980

Braunfels, Wolfgang. “I quadri di Tiziano nello studio a Biri Grande (1530–1576).” In Tiziano e Venezia: Convegno internazionale di studi (1976). Vicenza, 1980: 409.

Fasolo, Ugo. Titian. Florence, 1980: 69.

Guillaume, Marguerite. Peintures italiennes: Catalogue raisonné du Musée des Beaux-Arts de Dijon. Dijon, 1980: 85.

Heinemann, Fritz. “La bottega di Tiziano.” In Tiziano e Venezia: convegno internazionale di studi (1976). Vicenza, 1980: 435.

Hope, Charles. Titian. London, 1980: 149-150, 158-160, 167, 170.

Williams, Robert C.. Russian Art and American Money, 1900-1940. Cambridge, MA, 1980: 173.

1981

Siebenhüner, Herbert. Der Palazzo Barbarigo della Terrazza in Venedig und seine Tizian-Sammlung. Munich, 1981: 26, 28.

1982

Held, Julius. “Rubens and Titian.” In Titian: His World and His Legacy. Edited by David Rosand. New York, 1982: 291.

1983

Goodman-Soellner, Elise. “A Poetic Interpretation of the ‘Lady at her Toilette’ Theme in Sixteenth-Century Painting.” Sixteenth Century Journal 14 (1983): 434, 440-441.

Shearman, John. The Early Italian Pictures in the Collection of Her Majesty the Queen. Cambridge, 1983: 268.

1984

Walker, John. National Gallery of Art, Washington. Rev. ed. New York, 1984: 208, no. 253, color repro.

Ingenhoff-Danhäuser, Monika. Maria Magdalena: Heilige und Sünderin in der italienischen Renaissance. Tübingen, 1984: 65.

1985

European Paintings: An Illustrated Catalogue. National Gallery of Art, Washington, 1985: 395, repro.

1986

Gemäldegalerie Berlin: Gesamtverzeichnis der Gemälde. Berlin, 1986: 75, 456.

Borghero, Gertrude, ed. Thyssen-Bornemisza Collection. Catalogue Raisonné of the Exhibited Works of Art. Milan, 1986: 273.

Valcanover, Francesco. Ca d’Oro: The Giorgio Franchetti Gallery. Translated by Michael Langley. Milan, 1986: 47.

1987

Hart Nibbrig, Christiaan. Spiegelschrift: Spekulationen über Malerei und Literatur. Frankfurt, 1987: 18.

Wethey, Harold E. Titian and His Drawings, with Reference to Giorgione and Some Close Contemporaries. Princeton, 1987: 88 n. 32.

1988

Brown, Beverley Louise, and Arthur K. Wheelock, Jr. Masterworks from Munich: Sixteenth- to Eighteenth-Century Paintings from the Alte Pinakothek. Exh. cat. National Gallery of Art, Washington, 1988: 117-118.

Hope, Charles, “La produzione pittorica di Tiziano per gli Asburgo”. In Venezia e la Spagna. Milan, 1988: 64.

Rearick, W. R. The Art of Paolo Veronese, 1528-1588. Exh. cat. National Gallery of Art, Washington. Cambridge, 1988: 172.

1989

Tiziano, le lettere. Edited by Clemente Gandini from materials

compiled by Celso Fabbro. 2nd ed. Cadore, 1989: 269.

1990

Titian, Prince of Painters. Exh. cat. Palazzo Ducale, Venice; National Gallery of Art, Washington. Venice, 1990: 302-304.

1991

Kopper, Philip. America's National Gallery of Art: A Gift to the Nation. New York, 1991: 91, 94, color repro.

Gingold, Diane J., and Elizabeth A.C. Weil. The Corporate Patron. New York, 1991: 90-91, color repro.

1992

National Gallery of Art. National Gallery of Art, Washington. New York, 1992: 102, repro.

Fomichova, Tamara. The Hermitage Catalogue of West European Painting, Vol. 2: Venetian Painting of the Fourteenth to Eighteenth Centuries. Florence, 1992: 352.

Shearman, John. Only Connect...Art and the Spectator in the Italian Renaissance. Princeton, 1992: 228.

1993

Echols, Robert. "Titian's Venetian Soffitti: Sources and Transformations." Studies in the History of Art 45 (1993): 20.

Oberhuber, Konrad. “La mostra di Tiziano a Venezia.” Arte Veneta 44 (1993): 80-81.

Le Siècle de Titien. L’Âge d’Or de la Peinture à Venise. Exh. cat. Grand Palais, Paris, 1993: 534-535.

1994

Sheard, Wendy Stedman. “Le Siècle de Titien.” The Art Journal 53 (Spring 1994): 89.

1995

Stokstad, Marilyn. Art History. New York, 1995: 706, fig. 18.28.

Brevaglieri, Sabina. “Tiziano, le Dame con il Piatto e l’allegoria matrimoniale.” Venezia Cinquecento 5, no. 10 (1995): 134-135.

1997

Goffen, Rona. Titian's Women. New Haven and London, 1997: 133-139, no. 79, repro.

Santore, Cathy. "The Tools of Venus." in Renaissance Studies 11, no. 3. The Society for Renaissance Studies, Oxford University Press, 1997: 185, repro. no. 7.

Ekserdjian, David. Correggio. New Haven and London, 1997: 269-270.

Goffen, Rona. “Sex, Space and Social History in Titian’s Venus of Urbino.” In Titian’s Venus of Urbino. Edited by Rona Goffen. Cambridge, 1997: 75.

Pardo, Mary. “Veiling the Venus of Urbino.” In Titian’s Venus of Urbino. Edited by Rona Goffen. Cambridge, 1997: 122-123.

Schäpers, Petra. Die junge Frau bei der Toilette: Ein Bildthema im venezianischen Cinquecento. Frankfurt, 1997: 111-124.

1998

Medievalia et Humanistica: Studies in Medieval and Renaissance Culture. [Vol. 25]. Edited by Paul Maurice Clogan. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc., 1998: 58-61, repro. no. 2.

Roberts, Helene E., ed. Encyclopedia of Comparative Iconography: Themes Depicted in Works of Art. 2 vols. Chicago, 1998: 1:324, 326.

Cheney, Liana de Girolami. "Love and Death." In Encyclopedia of Comparative Iconography: Themes Depicted in Works of Art, edited by Helene E. Roberts. 2 vols. Chicago, 1998: 1:523.

Shefer, Elaine. "Mirror/Reflection." In Encyclopedia of Comparative Iconography: Themes Depicted in Works of Art, edited by Helene E. Roberts. 2 vols. Chicago, 1998: 2:602.

Apostolos-Cappadona, Diana. “Toilet Scenes." In Encyclopedia of Comparative Iconography: Themes Depicted in Works of Art. Edited by Helene E. Roberts. 2 vols. Chicago, 1998: 2:873.

1999

Valcanover, Francesco. Tiziano: I suoi pennelli sempre partorirono espressioni di vita. Florence, 1999: 67-71, 267.

2001

Pedrocco, Filippo. Titian: The Complete Paintings. London, 2001: 59, 67, 261, no. 218, repro.

2002

Anderson, Jaynie. “Titian’s Unfinished ‘Portrait of a Patrician Woman and Her Daughter’ from the Barbarigo Collection, Venice.” The Burlington Magazine 144 (2002): 671, 672, figs. 28 and 29.

Prater, Andreas. Venus at Her Mirror: Velázquez and the Art of Nude Painting. Munich, 2002: 21.

Checa Cremades, Fernando. Titian–Rubens: Venus ante el espejo. Exh. cat. Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid, 2002: 11-85.

2003

Freedman, Luba. The Revival of the Olympian Gods in Renaissance Art. Cambridge, 2003: 155, 190, 208.

2004

Hand, John Oliver. National Gallery of Art: Master Paintings from the Collection. Washington and New York, 2004: 100-101, no. 77, color repro.

Adams, Laurie Schneider. “Iconographic Aspects of the Gaze in some Paintings by Titian.” In The Cambridge Companion to Titian. Edited by Patricia Meilman. Cambridge, 2004: 232-233.

Puppi, Lionello. Su Tiziano. Milan, 2004: 77.

2006

Frank, Mary Engel. “'Donne attempate': Women of a Certain Age in Sixteenth-Century Venetian Art.” 2 vols. Ph.D. diss., Princeton University, 2006: 1:64-106, 303, 305, 306, fig. 46, 67, 77.

Tagliaferro, Giorgio. “La bottega di Tiziano: Un percorso critico.” Studi Tizianeschi 4 (2006): 45.

2007

Cranston, Jodi. “Theorizing Materiality: Titian’s Flaying of Marsyas.” In Titian: Materiality, Likeness, Istoria. Edited by Joanna Woods-Marsden. Turnhout, 2007: 15.

Humfrey, Peter. Titian: The Complete Paintings. Ghent and New York, 2007: 260.

Artemieva, Irina. “Die Venus vor dem Spiegel Barbarigo und der Dialogo della Pittura von Lodovico Dolce.” In Der späte Tizian und die Sinnlichkeit der Malerei. Edited by Sylvia Ferino-Pagden. Exh. cat. Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna; Gallerie dell'Accademia, Venice. Vienna, 2007: 224–231, 246-248.

Ferino-Pagden, Sylvia, ed. Der späte Tizian und die Sinnlichkeit der Malerei. Exh. cat. Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna; Gallerie dell'Accademia, Venice. Vienna, 2007: 248.

2008

Dal Pozzolo, Enrico Maria. Colori d’Amore. Parole, Gesti e Carezze nella Pitture Veneziana del Cinquecento. Treviso, 2008: 110, 129-131.

Hochmann, Michel. “Le collezioni veneziane nel Rinasacimento: Storia e storiografia.” In Il collezionismo d’arte a Venezia: Dalle origini al Cinquecento. Edited by Michel Hochmann, Rosella Lauber, and Stefania Mason. Venice, 2008: 17, 37.

2009

Odom, Anne, and Wendy R. Salmond, eds. Treasures into Tractors: The Selling of Russia's Cultural Heritage, 1918-1938. Washington, 2009: 82, 91, 106 n. 84, 106 n. 89, 131, 135 n. 62, repro.

Ilchman, Frederick, et al. Titian, Tintoretto, Veronese: Rivals in Renaissance Venice. Exh. cat. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; Musée du Louvre, Paris. Boston, 2009: 184-185.

Ilchman, Frederick, et al. Titien, Tintoret, Véronèse: Rivalités à Venise. Exh. cat., Musée du Louvre, Paris, 2009: 226-228.

Tagliaferro, Giorgio, and Bernard Aikema, with Matteo Mancini and Andrew John. Le botteghe di Tiziano. Florence, 2009: 32, 261.

2010

Cranston, Jodi. The Muddied Mirror: Materiality and Figuration in Titian’s Later Paintings. University Park, PA, 2010: 17, 21-31, 38-39, 48-49, 127.

2012

Paglia, Camille. Glittering Images: A Journey through Art from Egypt to Star Wars. New York, 2012: 48-51, color repro.

Reist, Inge. "The Classical Tradition: Mythology and Allegory." In Paolo Veronese: A Master and His Workshop in Renaissance Venice. Edited by Virginia Brilliant. Exh. cat. John and Mable Ringling Museum of Art, Sarasota. London and Sarasota, 2012: 117, 118, color fig. 43.

Gentili, Augusto. Tiziano. Milan, 2012: 253-255.

Hale, Sheila. Titian: His Life. London, 2012: 559-560, 731.

2013

Semyonova, Natalya, and Nicolas V. Iljine, eds. Selling Russia's Treasures: The Soviet Trade in Nationalized Art 1917-1938. New York and London, 2013: 138, 139, 200, repro.

2014

Mims, Bryan. "Asheville's Fortress of Art." Our State Down Home in North Carolina (1 October 2014): 40-42, 44, repro.

Grasso, Monica. Seguendo Tiziano: Viaggio nel ’500 sulle orme di un grande maestro. Rome, 2014: 91-92.

Humfrey, Peter. “The Chronology of Titian’s Versions of the Venus with a Mirror and the Lost Venus for the Emperor Charles V.” In Artistic Practices and Cultural Transfer in Early Modern Italy: Essays in Honour of Deborah Howard. Edited by Nabahat Avcioglu and Allison Sherman. Farnham and Burlington, VT, 2014: 221-232.

2016

Jaques, Susan. The Empress of Art: Catherine the Great and the Transformation of Russia. New York, 2016: 398.

2017

Serres, Karen. "Duveen's Italian framemaker, Ferruccio Vannoni." The Burlington Magazine 159, no. 1370 (May 2017): 374 n. 45.

2019

Linden, Diana L. "'In Honor of Dr. Martin Luther King': White Privilege and White Masks in William Christopher's Paintings of 1963." American Art 33, no. 3 (Fall 2019): 67, color fig. 9

2025

Harper, Mel. "Exhibitions and Programs. Back and Forth: Rozeal., Titian, Cezanne." _ Art for the Nation_ 70 (Summer 2025): 37, repro.

Wikidata ID

Q7920648