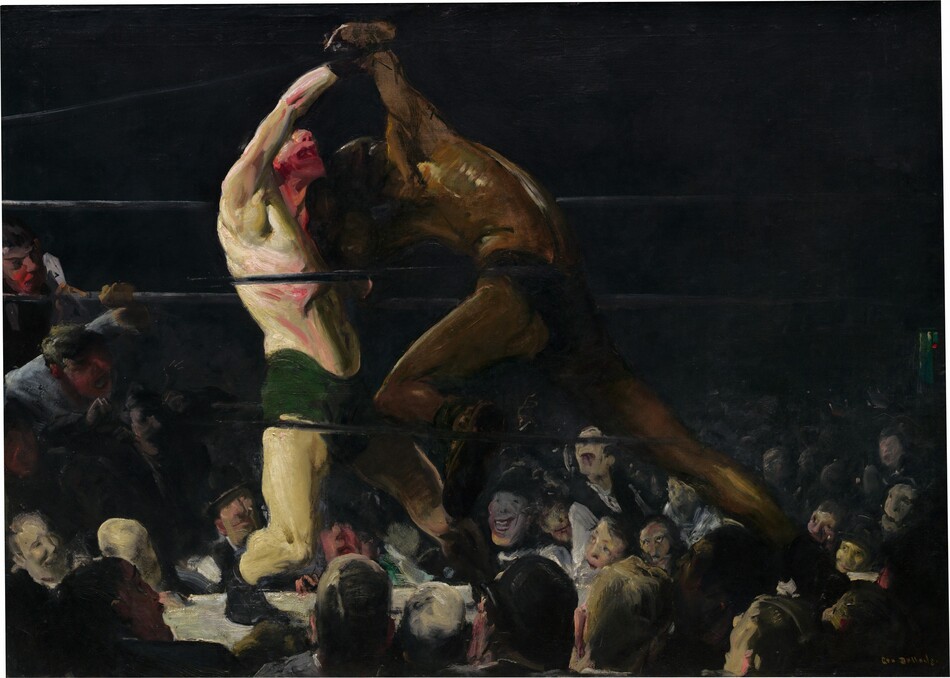

Both Members of This Club

1909

George Bellows

Painter, American, 1882 - 1925

Painted in October 1909, the remarkably expressive and dynamic Both Members of This Club is the third and largest of George Bellows’s early prizefighting subjects. The painting’s title is a reference to the practice in private athletic clubs of introducing the contestants to the audience as “both members” to circumvent the Lewis Law of 1900 that had banned public boxing matches in New York State. Boxing was a controversial subject, but the interracial theme made this painting even more so, especially since the black boxer appears to be winning the match.

It is likely that Bellows intended Both Members of This Club as an allusion to the recent and much-publicized success of the African American professional prizefighter Jack Johnson, who had won the world heavyweight championship in 1908. The idea of a black boxing champion was so unsettling to the prejudiced social order of the time that many thought interracial bouts should be outlawed. Painted at the height of the Jim Crow era, Bellows’s powerful delineation of a white fighter about to be defeated by a black opponent was an exceptionally daring and provocative piece of social commentary.

Artwork overview

-

Medium

oil on canvas

-

Credit Line

-

Dimensions

overall: 115 x 160.5 cm (45 1/4 x 63 3/16 in.)

framed: 133 x 177.8 cm (52 3/8 x 70 in.) -

Accession Number

1944.13.1

More About this Artwork

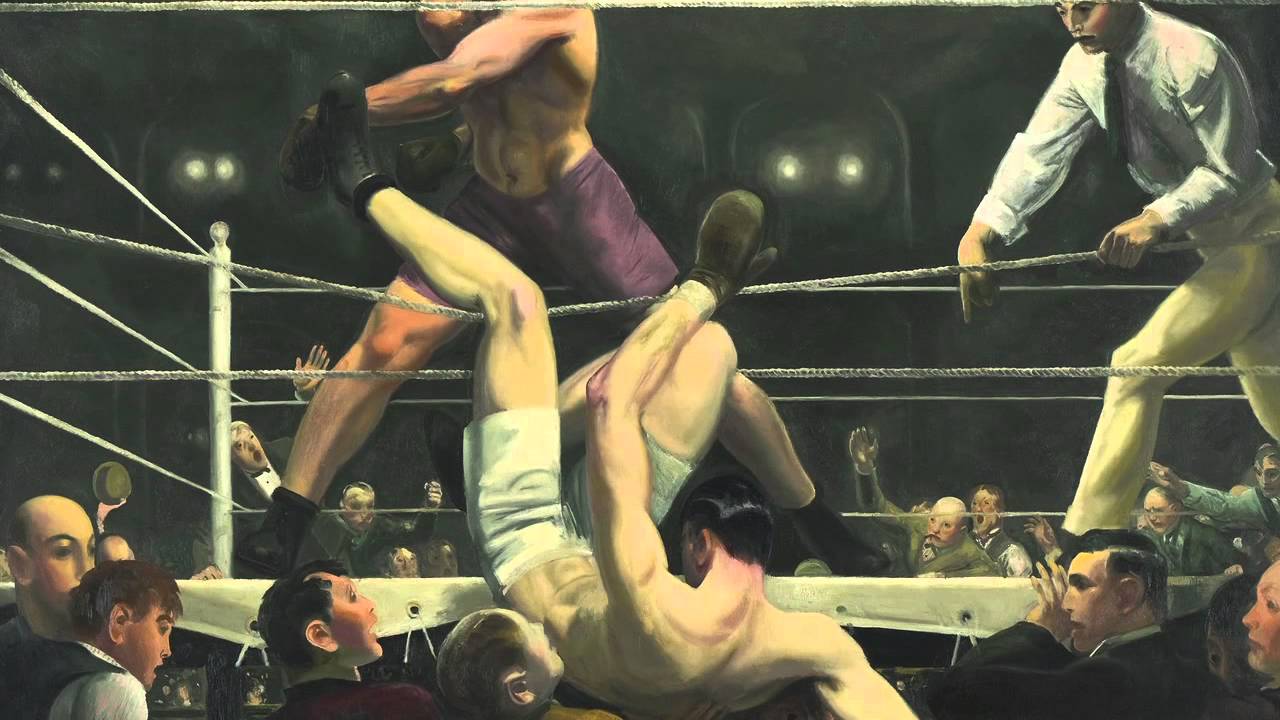

Video: George Bellows and the Art of Boxing

In this video, Sharmbá Mitchell, former two-time Junior Welterweight Champion of the World, and Charles Brock, associate curator of American and British paintings at the National Gallery of Art, Washington, talk about four of the greatest sports paintings in American art by George Bellows (1882–1925).

Artwork history & notes

Provenance

The artist [1882-1925]; by inheritance to his wife, Emma S. Bellows [1884-1959]; purchased 29 September 1944 through (H.V. Allison & Co., New York) by Chester Dale [1883-1962], New York; gift 1944 to NGA.

Associated Names

Exhibition History

1910

Exhibition of Independent Artists, Galleries at 29-31 West 35th Street, New York, April 1910, no. 53.

Fifth Annual Exhibition of Selected Paintings by American Artists, Albright Art Gallery, Buffalo, May-September 1910, no. 12.

One Hundred and Fifth Annual Exhibition, Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Philadelphia, January-March 1910, no. 338.

Fifth Annual Exhibition of Selected Paintings by American Artists, The City Art Museum, St. Louis, September-November 1910, no. 11.

1917

Exhibition of Paintings [by 12 different artists], The MacDowell Club, New York, 1917, no. 3.

1925

Memorial Exhibition of the Work of George Bellows, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 1925, no. 10, repro.

1940

Thirty-Six Paintings by George Bellows, Columbus Gallery of Fine Arts, Ohio, 1940, no catalogue.

1944

Art in Progress: Fifteenth Anniversary Exhibition: Painting, Sculpture, Prints, The Museum of Modern Art, New York, May-October 1944, unnumbered catalogue, repro. 39.

Paintings by George Bellows, H.V. Allison & Co., New York, March-April 1944, unnumbered checklist.

1946

George Bellows: Paintings, Drawings and Prints, Art Institute of Chicago, January-March 1946, no. 6, repro.

Robert Henri & Five of his Pupils, The Century Association, New York, April-June 1946, no. 6, repro.

1957

George Bellows: A Retrospective Exhibition, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., 1957, no. 14, repro.

1965

The Chester Dale Bequest, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., 1965, unnumbered checklist.

1982

Bellows: The Boxing Pictures, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., 1982, no. 3, fig. 29, pl. 5.

2012

George Bellows, National Gallery of Art, Washington; The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; Royal Academy of Arts, London, 2012-2013, pl. 18 (shown only in Washington).

Bibliography

1936

Barrows, Edward M. "George Bellows, Athlete." The North American Review 242, no. 2 (1 December 1936): 297.

Salpeter, Harry. "George Bellows, Native." Esquire 5, no. 4 (April 1936): 137.

1942

Boswell, Peyton, Jr. George Bellows. New York, 1942: 17.

1945

Watson, Jane. "Two Bellows Gifts Made Here." The Washington Post (7 January 1945): 11S.

Mechlin, Leila. "In the Art World: Two Paintings by George Bellows Acquired by National Gallery." The Washington Star (7 January 1945): C:6.

1952

Cairns, Huntington, and John Walker, eds., Great Paintings from the National Gallery of Art. New York, 1952: 180, color repro.

1959

Bouton, Margaret. American Painting in the National Gallery of Art. Washington, D.C., 1959 (Booklet Number One in Ten Schools of Painting in the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.): 40, color repro.

1963

Walker, John. National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. New York, 1963 (reprinted 1964 in French, German, and Spanish): 328, repro.

1965

Paintings other than French in the Chester Dale Collection. National Gallery of Art, Washington, 1965: 48, repro.

Morgan, Charles H. George Bellows. Painter of America. New York, 1965: 101-102, 104, repro. 323.

1966

Cairns, Huntington, and John Walker, eds. A Pageant of Painting from the National Gallery of Art. 2 vols. New York, 1966: 2:502, color repro.

1969

Young, Mahonri Sharp. "George Bellows: Master of the Prize Fight." Apollo 89 (February 1969): 138 fig. 8, 139.

1970

American Paintings and Sculpture: An Illustrated Catalogue. National Gallery of Art, Washington, 1970: 16, repro.

1971

Braider, Donald. George Bellows and the Ashcan School of Painting. New York, 1971: 54, fig. 8.

1973

Young, Mahonri Sharp. The Eight. New York, 1973: 42, color pl. 11.

1974

Gerdts, William H. The Great American Nude: A History in Art. New York, 1974: 158-162, fig. 8-5.

1978

King, Marian. Adventures in Art: National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. New York, 1978: 109, pl. 70.

1979

Watson, Ross. The National Gallery of Art, Washington. New York, 1979: 125-126, pl. 113.

1980

Wilmerding, John. American Masterpieces from the National Gallery of Art. National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., 1980: 17, no. 53, color repro.

American Paintings: An Illustrated Catalogue. National Gallery of Art, Washington, 1980: 26, repro.

1981

Williams, William James. A Heritage of American Paintings from the National Gallery of Art. New York, 1981: 205, color repro. 220.

1982

Carmean, E.A., Jr., et al. Bellows: The Boxing Pictures. Exh. cat. National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., 1982: no. 3, fig. 29, pl. 5, 32-36, 77-78.

1984

Walker, John. National Gallery of Art, Washington. Rev. ed. New York, 1984: 571, no. 869, color repro.

1988

Zurier, Rebecca. "Hey Kids: Children in the Comics & the Art of George Bellows." Print Collector's Newsletter 18, no. 6 (January-February 1988): 200-201, repro.

Wilmerding, John. American Masterpieces from the National Gallery of Art. Rev. ed. National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., 1988: 166, no. 60, color repro.

1990

Kelly, Frankin. "George Bellows' Shore House." Studies in the History of Art 37 (1990): 121, repro. no. 7.

1991

Kopper, Philip. America's National Gallery of Art: A Gift to the Nation. New York, 1991: 239, 242, color repro.

1992

American Paintings: An Illustrated Catalogue. National Gallery of Art, Washington, 1992: 29, repro.

National Gallery of Art, Washington. National Gallery of Art, Washington, 1992: 246, repro.

Doezema, Marianne. George Bellows and Urban America. New Haven and London, 1992: 101-113, fig. 44, color pl. 11.

Quick, Michael, Jane Myers, Marianne Doezema, and Franklin Kelly. The Paintings of George Bellows. Exh. cat. Los Angeles County Museum of Art; Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; Columbus (Ohio) Museum of Art; Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, 1992-1993. New York, 1992: 21-22, figs. 14 and 15.

Adams, Henry. "George Bellows [exh. review]." The Burlington Magazine 134, no. 1075 (October 1992): 686.

1994

Craven, Wayne. American Art: History and Culture. New York, 1994: 433, fig. 29.12.

Weinberg, H. Barbara, Doreen Bolger, and David Park Curry. American Impressionism and Realism: The Painting of Modern Life, 1885-1915. Exh. cat. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; Amon Carter Museum, Fort Worth; Denver Art Museum; Los Angeles County Museum of Art. New York, 1994: 240, fig. 225.

1995

Zurier, Rebecca, Robert W. Snyder, and Virginia M. Mecklenburg. Metropolitan Lives: The Ashcan Artists and Their New York. Exh. cat. National Museum of American Art, Washington. Washington and New York, 1995: 46-47, fig. 44.

Clark, Carol, and Allen Guttmann. "Artists and Athletes." Journal of Sports History 22 (Summer 1995): repro. 103, 104-105.

1997

Hughes, Robert. _ American Visions: The Epic History of Art in America_. New York, 1997: 334, color fig. 203.

1998

Pinkus, Karen. “Sport." In Encyclopedia of Comparative Iconography: Themes Depicted in Works of Art. Edited by Helene E. Roberts. 2 vols. Chicago, 1998: 2:855, 856.

2004

Hand, John Oliver. National Gallery of Art: Master Paintings from the Collection. Washington and New York, 2004: 404, no. 333, color repro.

2005

Mathews, Nancy Mowll., et al. Moving Pictures; American Art and Early Film, 1880-1910. Exh. cat. Williams College Museum of Art, Williamstown; Reynolda House, Museum of American Art, Winston-Salem; Grey Art Gallery & Study Center, New York University; The Phillips Collection, Washington; 2005-2007. Manchester, 2005: 114 fig. 178, 115.

2009

Peck, Glenn C. George Bellows' Catalogue Raisonné. H.V. Allison & Co., 2009. Online resource, URL: http://www.hvallison.com. Accessed 16 August 2016.

2011

Corebett, David Peters. "Camden Town and the Ashcan: Difference, Similarity and the 'Anglo-American' in the Work of Walter Sickert and John Sloan." Art History 34, no. 4 (September 2011): 791.

2012

Brock, Charles, et al. George Bellows. Exh. cat. National Gallery of Art, Washington; The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; Royal Academy of Arts, London, 2012-2013. Washington and New York, 2012: 10-11, 23, 71, 73, 77, 78, 215, pl. 18.

2013

Corbett, David Peters. The American Experiment: George Bellows and the Ashcan Painters, with Katherine Bourguignon and Christopher Riopelle. London, 2013: 21, 22, color fig. 6.

2016

National Gallery of Art. Highlights from the National Gallery of Art, Washington. Washington, 2016: 274, repro.

Inscriptions

lower right: Geo Bellows

Wikidata ID

Q12857837