Berlin Abstraction

1914/1915

Marsden Hartley

Painter, American, 1877 - 1943

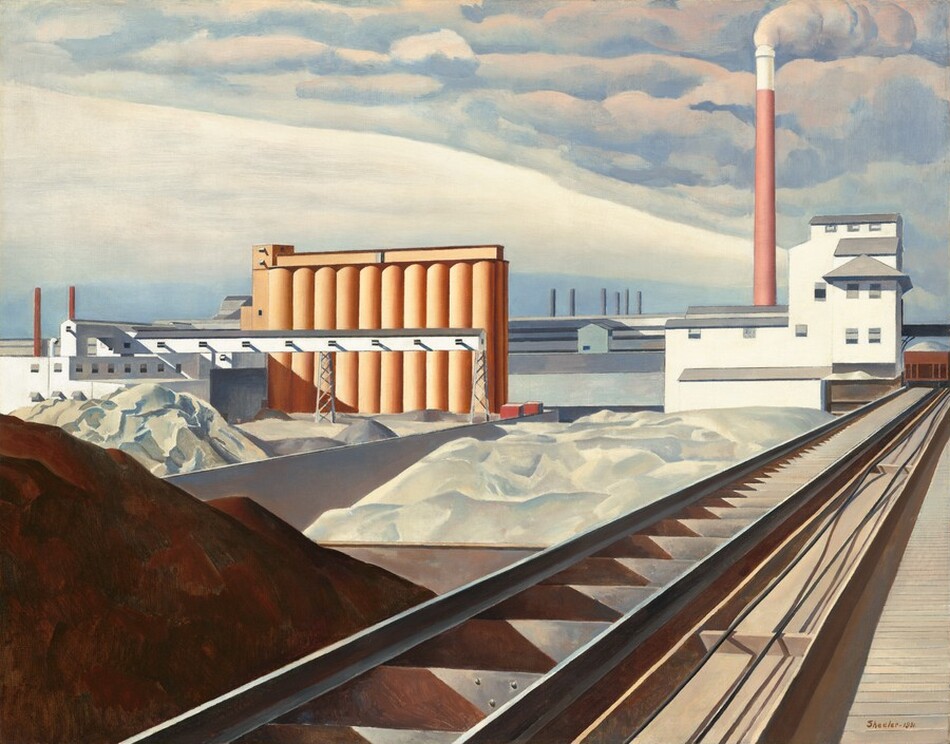

Berlin Abstraction is one of more than a dozen deeply symbolic and personal paintings Marsden Hartley produced in 1914 and 1915. These oils contain coded references to Hartley's life in Berlin's vibrant LGBTQ culture and the role of the German military in that culture, as well as an outpouring of the artist's thoughts about war. In particular, they memorialize the artist's cherished friend Karl von Freyburg, a young German lieutenant killed in action during World War I.

The mosaiclike arrangement of symbols and signs in Berlin Abstraction evokes the military pageantry that so impressed Hartley in Berlin: the sleeve cuffs and epaulets of uniforms; a helmet cockade denoted by two concentric circles; and the blue-and-white, diamond-patterned Bavarian flag. Other symbols refer specifically to Freyburg: the red number four signifies the Fourth Regiment of the Kaiser's guards, in which he fought, and the red-and-white checkerboard pattern recalls his love of chess. The central black cross on a white background circumscribed by red and white circles is likely an abstraction of the Iron Cross medal for bravery, which was bestowed posthumously on Freyburg. The calligraphic red letter E refers to Elisabeth, queen of Greece, the patroness of the regiment of Freyburg's cousin, sculptor Arnold Rönnebeck. The painting was strongly influenced by modernism, to which Hartley had been exposed during his European study. For example, the juxtaposition of flat, geometric, black-outlined shapes evidences his interest in synthetic cubism, which he saw in Pablo Picasso's paintings at Gertude and Leo Stein's famous 1912 salon in Paris, where he also met the artist.

Artwork overview

-

Medium

oil on canvas

-

Credit Line

-

Dimensions

overall: 80.8 × 64.8 cm (31 13/16 × 25 1/2 in.)

framed: 101 × 85.1 × 5.7 cm (39 3/4 × 33 1/2 × 2 1/4 in.) -

Accession Number

2014.79.21

More About this Artwork

Article: 15 LGBTQ+ Artists to Know

Discover the lives of 15 LGBTQ+ artists and their art, much of which you can see at the National Gallery.

Artwork history & notes

Provenance

Probably collection of the artist [1877-1943], Maine;[1] probably Alfred Stieglitz [1864-1946], New York.[2] Paul L. Rosenfeld [1890-1946], New York;[3] bequest 1946 to Arthur Schwab and Edna Bryner Schwab [1886-1967], New York;[4] consigned 1946 to (Downtown Gallery, New York);[5] consigned to (sale, Kende Galleries at Gimbel Brothers, New York, 17-18 January 1947, 1st day, no. 65); purchased January 1947 by Ione [1915-1987] and Hudson [1907-1976] Walker, Minneapolis;[6] (Babcock Galleries, New York), February 1966;[7] purchased 30 January 1967 by the Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington; acquired 2014 by the National Gallery of Art.

[1] There is no will on file for the artist. There are, however, documents in the Hancock County Probate Court, Ellsworth, Maine, related to Hartley's estate that list paintings in his collection; copies in NGA curatorial files. The list titled "Schedule of Personal Estate...Goods & Chattels" includes one painting (item no. 138) that could be Berlin Abstraction: "Painting #8," 25 1/2 x 31 1/2 in.

[2] Card files of Michael St. Clair, owner of Babcock Galleries from 1959 to 1989; see e-mail correspondence, 11 January 2007, Lisa Koonce, Babcock Galleries, to Emily Shapiro, assistant curator of American art, Corcoran Gallery of Art, in NGA curatorial files.

[3] Elizabeth McCausland Papers, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington: reel D269, frames 551-555; reel D274, frame 68; copies in NGA curatorial files.

[4] Paul Rosenfeld will, dated 22 October 1937, proved 7 August 1946, Surrogate's Court, County of New York; copy in NGA curatorial files.

[5] Records of the Downtown Gallery, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington: Series I: Correspondence; letter of 13 November 1946, Edith G. Halpert, president, The Downtown Gallery, to Miss Edna Bryner and Mr. Arthur Schwab; reel 5498, frames 965 and 968; copy in NGA curatorial files.

[6] Elizabeth McCausland Papers, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington: reel D269, frames 551-555; reel D274, frame 68; copies in NGA curatorial files.

[7] E-mail correspondence of 10 January 2007, Lisa Konce, Babcock Galleries, to Emily Shapiro, assistant curator of American art, Corcoran Gallery of Art; in NGA curatorial files.

Associated Names

Exhibition History

1915

Probably Haas-Heye Galerie of the Münchener Graphik Verlag, Berlin, October 1915.

1916

Probably Paintings by Marsden Hartley, Photo-Secession Galleries, New York, 4 April - 22 May 1916, unnumbered catalogue.

1950

Loan to display with permanent collection, University Gallery, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, 1950s-1965.

1960

Marsden Hartley, McNay Art Institute, San Antonio; Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam; Amerika Haus, Berlin; Stadtische Galerie München in Verbindung mit dem Amerika Haus, Munich; Kunstmuseum der Stadt Amerika Düsseldorf in Verbindung mit dem Amerikanischen Generalkonsultat, Dusseldorf; American Embassy, London; Walker Art Center, Minneapolis; City Art Museum, Saint Louis; Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, 1 December 1960 - 31 January 1962, no. 16.

1980

Marsden Hartley, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; Art Institute of Chicago, 5 March - 3 August 1980, no. 107.

2004

Figuratively Speaking: The Human Form in American Art, 1770-1950, Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington, 20 November 2004 - 7 August 2005, unpublished checklist.

2005

Encouraging American Genius: Master Paintings from the Corcoran Gallery of Art, Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington; Museum of Fine Arts, Houston; Parrish Art Museum, Southampton; Mint Museum of Art, Charlotte; John and Mable Ringling Museum of Art, Sarasota, 2005-2007, checklist no. 72.

2008

The American Evolution: A History through Art, Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington, 1 March - 27 July 2008, unpublished checklist.

2009

American Paintings from the Collection, Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington, 6 June - 18 October 2009, unpublished checklist.

2012

Inventing Abstraction, Museum of Modern Art, New York, 23 December 2012 - 15 April 2013, no. 153.

2013

American Journeys: Visions of Place, Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington, 21 September 2013 - 28 September 2014, unpublished checklist (removed early from this exhibition for loan to the 2014 exhibition in Berlin and Los Angeles).

2014

Marsden Hartley: The German Paintings, Neue Nationalgalerie, Berlin; Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 2014, unnumbered catalogue, repro.

Bibliography

1947

"1st Editions to Go on Sale Tomorrow." New York Times (12 January 1947): 63.

1952

McCausland, Elizabeth. Marsden Hartley. Minneapolis, 1952: 26, 66.

1967

Hudson, Andrew. "Viewpoint on Art: Capital's Museums Grow in Prestige." The Washington Post and Times Herald (28 May 1967): K:7, repro.

Hudson, Andrew. "Around the Galleries." The Washington Post and Times Herald (26 March 1967): H:7.

Harithas, James. "Marsden Hartley's German Period Abstractions." The Corcoran Gallery of Art Bulletin 16, no. 3 (November 1967): 22, repro., 24.

1968

Corcoran Gallery of Art. "The Annual Report of the One Hundred and Ninth Year." The Corcoran Gallery of Art Bulletin 16, no. 4 (June 1968): cover, 4, 26, repro.

1973

Phillips, Dorothy W. A Catalogue of the Collection of American Paintings in the Corcoran Gallery of Art, Vol. 2: Painters born from 1850 to 1910. Washington, 1973: 98, repro., 99.

1979

Levin, Gail. “Hidden Symbolism in Marsden Hartley’s Military Pictures.” Arts Magazine 54 (October 1979): 157, fig. 13, 158.

1984

Corcoran Gallery of Art. American Painting: The Corcoran Gallery of Art. Washington, 1984: 34, repro., 35.

1988

Scott, Gail R. Marsden Hartley. New York, 1988: 53, 55, pl. 39.

1995

McDonnell, Patricia. Dictated by Life: Marsden Hartley's German Paintings and Robert Indiana's Hartley Elegies. Exh. cat. Frederick R. Weisman Art Museum, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, 1995: 31, 52, repro.

2000

Cash, Sarah, with Terrie Sultan. American Treasures of the Corcoran Gallery of Art. New York, 2000: 161, 172, repro.

2002

Heartney, Eleanor, ed. A Capital Collection: Masterworks from the Corcoran Gallery of Art. London, 2002: 18 (detail), 19, 38-39, repro.

2006

Patterson, Tom. "Just Visiting: Major American Works from the Corcoran Gallery are Ending the Year at Charlotte's Mint Museum [exh. review]." Winston-Salem Journal (3 December 2006): F:9

Shinn, Susan. "Viewing Masters: 'Encountering American Genius: Master Paintings from the Corcoran Gallery of Art' Opens at the Mint [exh. review]." Salisbury Post (12 October 2006): D:7.

"Celebrating American Genius [exh. review]." New York Sun (6 July 2006): 1, repro, 16.

2007

Bennett, Lennie. "The Coming of Age of American Art [exh. review]." St. Petersburg Times (18 February 2007): 9L, repro.

2011

Cash, Sarah. "Marsden Hartley, Berlin Abstraction." In Corcoran Gallery of Art: American Paintings to 1945. Edited by Sarah Cash. Washington, 2011: 210-211, 278-279, repro.

2014

"The Corcoran Gallery of Art - A New Beginning." American Art Review 16, no. 2 (March-April 2014): 139, repro.

Scholz, Dieter, ed. Marsden Hartley: The German Paintings 1913-1915 Exh. cat. Neue Nationalgalerie, Berlin; Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Berlin, Los Angeles, and New York, 2014: 90 repro., 204.

Inscriptions

Verso: stickers, Babcock Gallery, American Federation of Arts, University Gallery, University of Minnesota.

Wikidata ID

Q20191813