A Naval Encounter between Dutch and Spanish Warships

c. 1618/1620

Cornelis Verbeeck

Painter, Dutch, 1590/1591 - 1637

In 1995 two marine paintings, Dutch Warship Attacking a Spanish Galley and Spanish Galleon Firing Its Cannons, were bequeathed to the National Gallery of Art. Technical examinations determined that the panels originally had formed a single painting that was subsequently cut in half to form two separate works. Dendrochronological analysis revealed that the two horizontally joined oak panel boards from each segment came from the same trees. This technical information, coupled with compositional evidence, such as corresponding cloud and wave patterns on the two segments, demonstrated that the two panels had once formed a continuous larger composition with the Spanish Galleon Firing Its Cannons panel on the left and the Dutch Warship Attacking a Spanish Galley panel on the right. Fortunately, the two panels had remained together throughout their history, and after they were conserved in 2009–2010, they were brought together to reestablish the original appearance of Verbeeck’s work.

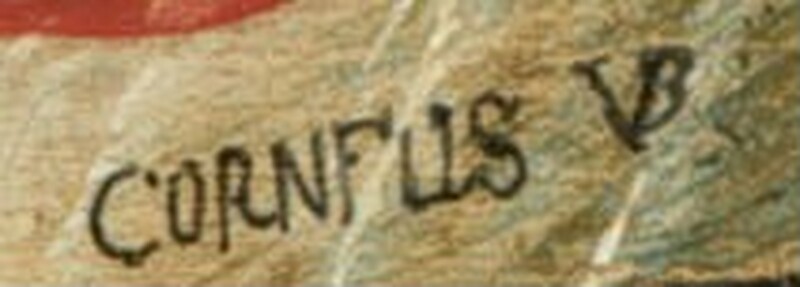

This reconstructed painting, now titled A Naval Encounter between Dutch and Spanish Warships, vividly depicts an intense naval engagement, characteristic of Dutch battles against Spain during the long Dutch Revolt. At right a Dutch warship under full sail has already destroyed a small Spanish galley that is sinking in the stormy sea. The Dutch ship is alive with triumphant activity, from the commander and trumpeter standing on the poop deck beneath the red flag to the sailors scurrying up the rigging and the soldiers reloading their muskets. At left a Spanish galleon is firing its portside cannons toward the large Dutch warship while trying to hit another Dutch ship with its starboard cannons. The smaller Dutch vessel, in the left background, has already reduced a Spanish galley to a burning wreck. Verbeeck’s painting, which the artist signed Cornelis VB on the red, white, and blue Dutch flag atop the main mast, does not appear to represent an actual battle scene but seems to be a nautical metaphor celebrating the victory of the Dutch people over their enemy.

Artwork overview

-

Medium

oil on panel

-

Credit Line

-

Dimensions

overall (sight size): 47.63 x 141.61 cm (18 3/4 x 55 3/4 in.)

framed: 66.68 x 159.39 cm (26 1/4 x 62 3/4 in.) -

Accession Number

1995.21.1-2

More About this Artwork

Artwork history & notes

Provenance

Henry Villard [1835-1900], New York, by the 1880s; by descent to his granddaughter, Dorothea Villard Hammond [1907-1994], Washington, D.C.; bequest 1995 to NGA.

Associated Names

Exhibition History

2018

Water, Wind, and Waves: Marine Paintings from the Dutch Golden Age, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., 2018, unnumbered brochure.

Bibliography

2007

Wheelock, Arthur K., Jr., and Michael Swicklik. "Behind the Veil: Restoration of a Dutch Marine Painting Offers a New Look at Seventeenth-Century Dutch Art and History." National Gallery of Art Bulletin no. 37 (Fall 2007): 2-13, figs. 1, 11, 12.

2020

Kattenburg, Rob, et al. Cornelis Isaacz. Verbeeck, The discovery of a masterpiece: The Blockade of the Privateers' Nest at Dunkirk with the 'Vlieghende Groene Draeck', left in the foreground. Bergen, 2020: 7, fig. 6.

Inscriptions

on the Dutch flag: Cornelis VB

Wikidata ID

Q20176969