The Dancing Couple

1663

Jan Steen

Artist, Dutch, 1625/1626 - 1679

Jan Steen’s paintings encompass a wide range of moods and subjects, from intimate scenes of a family saying grace before a meal to festive village celebrations, yet all of his paintings elicit a warm reaction to the lives of ordinary people. All five senses are represented in this work in which two young musicians play for a dancing couple while other people in the vine-covered arbor flirt, eat, drink, or smoke, and children amuse themselves with their toys. The grinning figure on the left who caresses the chin of the woman drinking from an elegant wine glass is none other than Steen himself. Despite the apparent frivolity of the scene, Steen used emblematic references such as cut flowers, broken eggshells, and soap bubbles to warn the viewer about the transience of sensual pleasures.

Many of Steen’s greatest paintings are large, complex scenes of families and merrymakers containing witty evocations of proverbs, emblems, or other moralizing messages. His pictures, which are marked by a sophisticated use of contemporary literature and popular theater, often depict characters from both the Italian commedia dell’arte and the native Dutch rederijkerskamers (rhetoricians’ chambers). Steen, one of the most versatile and prolific Dutch painters of the seventeenth century, was apparently less adept in his other profession as a brewer and innkeeper because, legend has it, he drank too much of his own inventory and spent more money than he earned. The relative chaos and merry mood of his paintings gave rise to the Dutch saying "to run a household like Jan Steen," meaning to have a disorderly house.

West Building Main Floor, Gallery 46

Artwork overview

-

Medium

oil on canvas

-

Credit Line

-

Dimensions

overall: 102.5 x 142.5 cm (40 3/8 x 56 1/8 in.)

framed: 131.4 x 171.8 cm (51 3/4 x 67 5/8 in.) -

Accession Number

1942.9.81

More About this Artwork

Artwork history & notes

Provenance

Possibly (sale, The Hague, 24 April 1737, no. 7). probably Graf van Hogendorp; probably (his sale, The Hague, 27 July 1751, no. 6).[1] Pieter Bisschop [c. 1690-1758] and Jan Bisschop [1680-1771], Rotterdam, by 1752; purchased 1771 with the Bisschop collection by Adrian Hope [1709-1781] and his nephew, John Hope [1737-1784], Amsterdam; by inheritance after Adrian's death to John, Amsterdam and The Hague; by inheritance to his sons, Thomas Hope [1769-1831], Adrian Elias Hope [1772-1834], and Henry Philip Hope [1774-1839], Bosbeek House, near Heemstede, and, as of 1794, London, where the collection was in possession of John's cousin, Henry Hope [c. 1739-1811], London; by inheritance 1811 solely to Henry Philip, Amsterdam and London, but in possession of his brother, Thomas, London; by inheritance 1839 to Thomas' son, Henry Thomas Hope [1808-1862], London, and Deepdene, near Dorking, Surrey; by inheritance to his wife, Adèle Bichat Hope [d. 1884], London and Deepdene; by inheritance to her grandson, Henry Francis Hope Pelham-Clinton-Hope, 8th duke of Newcastle-under-Lyme [1866-1941], London; (P. & D. Colnaghi & Co. and Charles J. Wertheimer, London), 1898-1901; (Thos. Agnew & Sons, Ltd., London); sold 1901 to Peter A.B. Widener, Lynnewood Hall, Elkins Park, Pennsylvania; inheritance from Estate of Peter A.B. Widener by gift through power of appointment of Joseph E. Widener, Elkins Park; gift 1942 to NGA.

[1] Mariët Westermann kindly brought the 1751 sale to the attention of Arthur K. Wheelock, Jr. For a discussion of the provenance of this painting, including the 1737 sale, see Ben Broos, Great Dutch Paintings from America, exh. cat., Mauritshuis, The Hague; Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, Zwolle and The Hague, 1990: 419-423.

Associated Names

- Sale, The Hague

- Hogendorp, Graf van

- Bisschop, Jan

- Bisschop, Pieter

- Hope, Adrian

- Hope, John

- Hope, Adrian Elias

- Hope, Thomas

- Hope, Henry Philip

- Hope, Henry Thomas

- Hope, Henry Thomas, Mrs.

- Pelham-Clinton-Hope, Henry Francis Hope, 8th duke of Newcastle-under-Lyme

- Wertheimer, Charles J.

- P. & D. Colnaghi & Co., Ltd.

- Thomas Agnew & Sons, Ltd.

- Widener, Peter Arrell Brown

- Widener, Joseph E.

Exhibition History

1818

British Institution for Promoting the Fine Arts in the United Kingdom, London, 1818, no. 138, as Merrymaking.

1849

British Institution for Promoting the Fine Arts in the United Kingdom, London, 1849, no. 84, as A Merrymaking.

1866

Possibly British Institution for Promoting the Fine Arts in the United Kingdom, London, 1866, no. 33, as A Dinner Party.

1881

Exhibition of of Works by the Old Masters, and by Deceased Masters of the British School. Winter Exhibition, Royal Academy of Arts, London, 1881, no. 124, as A Village Fête.

1891

The Hope Collection of Pictures of the Dutch and Flemish Schools, The South Kensington Museum, London, 1891-1898, no. 25.

1909

The Hudson-Fulton Celebration, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 1909, no. 126.

1925

Loan Exhibition of Dutch Paintings of the Seventeenth Century, Detroit Institute of Arts, 1925, no. 26.

1990

Great Dutch Paintings from America, Mauritshuis, The Hague; The Fine Arts Musuems of San Francisco, M. H. de Young Memorial Museum, 1990-1991, no. 59, color repro., as Dancing Couple at an Inn.

1996

Jan Steen: Painter and Storyteller, National Gallery of Washington, D.C.; Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, 1996-1997, no. 20, repro.

2003

Loan for display with permanent collection, The National Gallery, London, 2003-2004.

Bibliography

1771

Kabinet van schilderijen, berustende, onder den heere Jan Bisschop te Rotterdam. Rotterdam, 1771: 10.

1797

Reynolds, Sir Joshua. "A Journey to Flanders and Holland, in the Year MDCCLXXXI." In The Works of Sir Joshua Reynolds, Knt. Late President of the Royal Academy. 2 vols. Edited by Edmond Malone. London, 1797: 2:77.

1818

British Institution for Promoting the Fine Arts in the United Kingdom. Catalogue of pictures of the Italian, Spanish, Flemish, Dutch, and French schools. Exh. cat. British Institution. London, 1818: no. 138.

1824

British Institution for Promoting the Fine Arts in the United Kingdom. An Account of All the Pictures Exhibited in the Rooms of the British Institution, from 1813 to 1823, Belonging to the Nobility and Gentry of England: with Remarks, Critical and Explanatory. London, 1824: 172, no. 7 or 9.

Westmacott, C. M. British Galleries of Painting and Sculpture: Comprising a General Historical and Critical Catalogue with Separate Notices of Every Work of Fine Art in Principal Collections. London, 1824: 233.

1829

Smith, John. A Catalogue Raisonné of the Works of the Most Eminent Dutch, Flemish and French Painters. 9 vols. London, 1829-1842: 4(1833):50, no. 150.

1838

Waagen, Gustav Friedrich. Works of Art and Artists in England. 3 vols. Translated by H. E. Lloyd. London, 1838: 2:334.

1849

British Institution for Promoting the Fine Arts in the United Kingdom. A catalogue of the works of British artists placed in the gallery of the British institution. Exh. cat. British Institution, London, 1849: no. 84.

1854

Waagen, Gustav Friedrich. Treasures of Art in Great Britain: Being an Account of the Chief Collections of Paintings, Drawings, Sculptures, Illuminated Mss.. 3 vols. Translated by Elizabeth Rigby Eastlake. London, 1854: 2:118.

1856

Westrheene Wz., Tobias van. Jan Steen: Étude sur l'art en Hollande. The Hague, 1856: 119-120, no. 89.

1866

British Institution for Promoting the Fine Arts in the United Kingdom. Catalogue of pictures by Italian, Spanish, Flemish, Dutch, Franch, and English masters. Exh. cat. British Institution. London, 1866: 9, no. 33.

1881

Royal Academy of Arts. Exhibition of of Works by the Old Masters, and by Deceased Masters of the British School. Winter Exhibition. Exh. cat., Royal Academy of Arts, London, 1881: no. 124.

Royal Academy of Arts. Exhibition of Works by The Old Masters and by Deceased Masters of the British School...Winter Exhibition. Exh. cat. Royal Academy of Arts, London, 1881: no. 124.

1885

Catalogue of Paintings Forming the Collection of P.A.B. Widener, Ashbourne, near Philadelphia. 2 vols. Paris, 1885-1900: 2(1900):165.

1891

South Kensington Museum. A catalogue of pictures of the Dutch and Flemish schools lent to the South Kensington Museum by Lord Francis Pelham Clinton-Hope. Exh. cat. South Kensington Museum. London, 1891: no. 25.

South Kensington Museum. A catalogue of pictures of the Dutch and Flemish schools lent to the South Kensington Museum by Lord Francis Pelham Clinton-Hope. (Exh. cat. South Kensington Museum). London, 1891: no. 25.

1898

South Kensington Museum. The Hope Collection of Pictures of the Dutch and Flemish Schools with Descriptions Reprinted from the Catalogue Published in 1891 by the Science and Art Department of the South Kensington Museum. London, 1898: no. 25, repro.

1907

Thieme, Ulrich, and Felix Becker. Allgemeines Lexikon der bildenden Künstler von der Antike bis zur Gegenwart. 37 vols. Leipzig, 1907-1950: 31(1937): 512.

Hofstede de Groot, Cornelis. A Catalogue Raisonné of the Works of the Most Eminent Dutch Painters of the Seventeenth Century. 8 vols. Translated by Edward G. Hawke. London, 1907-1927: 1(1907):171-172, no. 655.

Hofstede de Groot, Cornelis. Beschreibendes und kritisches Verzeichnis der Werke der hervorragendsten holländischen Maler des XVII. Jahrhunderts. 10 vols. Esslingen and Paris, 1907-1928: 1(1907):159, no. 655.

1909

Valentiner, Wilhelm R. Catalogue of a collection of paintings by Dutch masters of the seventeenth century. The Hudson-Fulton Celebration 1. Exh. cat. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 1909: xxvii, 127, no. 126, repro., 157, 162.

1910

Breck, Joseph. "Hollandsche kunst op de Hudson-Fulton tentoonstelling te New York." Onze Kunst 17 (February 1910): 44.

Valentiner, Wilhelm R. "Die Ausstellung holländischer Gemälde in New York." Monatshefte für Kunstwissenschaft 3 (1910): 10.

Wiersum, E. "Het schilderijen-kabinet van Jan Bisschop te Rotterdam." Oud Holland 28 (Summer 1910): 171.

Valentiner, Wilhelm R. Catalogue of a Loan Exhibition of Paintings by Old Dutch Masters Held at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in Connection with the Hudson-Fulton Celebration. New York, 1910: 15, repro. 426, 427, no. 126.

1913

Hofstede de Groot, Cornelis, and Wilhelm R. Valentiner. Pictures in the collection of P. A. B. Widener at Lynnewood Hall, Elkins Park, Pennsylvania: Early German, Dutch & Flemish Schools. Philadelphia, 1913: unpaginated, repro.

1923

Paintings in the Collection of Joseph Widener at Lynnewood Hall. Intro. by Wilhelm R. Valentiner. Elkins Park, Pennsylvania, 1923: unpaginated, repro.

1925

Valentiner, Wilhelm R. Loan Exhibition of Dutch Paintings of the Seventeenth Century. Exh. cat. Detroit Institute of Arts. Detroit, 1925: no. 26.

Washburn-Freund, Frank E. "Eine Ausstellung niederländischer Malerei in Detroit." _Der Cicerone _ 17 (1925): 463.

1931

Paintings in the Collection of Joseph Widener at Lynnewood Hall. Intro. by Wilhelm R. Valentiner. Elkins Park, Pennsylvania, 1931: 220, repro.

1938

Waldmann, Emil. "Die Sammlung Widener." Pantheon 22 (November 1938): 336, 338.

1948

National Gallery of Art. Paintings and Sculpture from the Widener Collection. Washington, 1948: 53, repro.

1954

Martin, Wilhelm. Jan Steen. Amsterdam, 1954: 79.

1957

Shapley, Fern Rusk. Comparisons in Art: A Companion to the National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC. London, 1957 (reprinted 1959): pl. 108.

1958

Domela Nieuwenhuis, Peder Niels Hjalmar, and Anton van Duinkerken. Jan Steen. Exh. cat. Royal Picture Gallery Mauritshuis, The Hague, 1958: no. 18.

1959

National Gallery of Art. Paintings and Sculpture from the Widener Collection. Reprint. Washington, DC, 1959: 53, repro.

1960

Baird, Thomas P. Dutch Painting in the National Gallery of Art. Ten Schools of Painting in the National Gallery of Art 7. Washington, 1960: 28, color repro.

The National Gallery of Art and Its Collections. Foreword by Perry B. Cott and notes by Otto Stelzer. National Gallery of Art, Washington (undated, 1960s): 25.

1961

Bille, Clara. De Tempel der Kunst of Het Kabinet van den Heer Braamcamp. 2 vols. Amsterdam, 1961: 1:105.

1963

Walker, John. National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. New York, 1963 (reprinted 1964 in French, German, and Spanish): 35, 315, repro., 344.

1964

Constable, William George. Art Collecting in the United States of America: An Outline of a History. London, 1964: 117.

1965

National Gallery of Art. Summary Catalogue of European Paintings and Sculpture. Washington, 1965: 124.

1966

Cairns, Huntington, and John Walker, eds. A Pageant of Painting from the National Gallery of Art. 2 vols. New York, 1966: 1: 242, color repro.

1968

National Gallery of Art. European Paintings and Sculpture, Illustrations. Washington, 1968: 111, repro.

1974

Buist, Marten G. At Spes Non Fracta: Hope & Co. 1770-1815: Merchant Bankers and Diplomats at Work. The Hague, 1974: 492.

1975

National Gallery of Art. European paintings: An Illustrated Summary Catalogue. Washington, 1975: 332, repro.

Walker, John. National Gallery of Art, Washington. New York, 1975: 291, no. 385, color repro.

1977

Vries, Lyckle de. "Jan Steen, 'de kluchtschilder'." Ph.D. dissertation, Rijksuniversiteit, Groningen, 1977: 53-54, 162, no. 97.

1978

King, Marian. Adventures in Art: National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. New York, 1978: 59, pl. 33.

1980

Braun, Karel. Alle tot nu toe bekende schilderijen van Jan Steen. Rotterdam, 1980: 110-111, no. 180, repro.

1981

Niemeijer, J. W. "De kunstverzameling van John Hope (1737–1784)." Nederlands Kunsthistorisch Jaarboek 32 (1981): 197, no. 216.

1984

Sutton, Peter C. Masters of Seventeenth-Century Dutch Genre Painting. Edited by Jane Iandola Watkins. Exh. cat. Philadelphia Museum of Art; Gemäldegalerie, Staatliche Museen Preussischer Kulturbesitz, Berlin; Royal Academy of Arts, London. Philadelphia, 1984: 312, fig. 2.

Walker, John. National Gallery of Art, Washington. Rev. ed. New York, 1984: 291, no. 379, color repro.

Wheelock, Arthur K., Jr. Dutch Painting in the National Gallery of Art. Washington, D.C., 1984: 6, 34-35, color repro.

1985

National Gallery of Art. European Paintings: An Illustrated Catalogue. Washington, 1985: 381, repro.

1986

Ford, Terrence, compiler and ed. Inventory of Music Iconography, no. 1. National Gallery of Art, Washington. New York 1986: 6, no. 128.

Sutton, Peter C. A Guide to Dutch Art in America. Grand Rapids and Kampen, 1986: 309, repro. 461.

1990

Buijsen, Edwin. "De kunst van het verzamelen: De verzamelaar centraal op Haags symposium." Tableau 13 (December 1990): 64-66, fig. 2.

Schneider, Cynthia P. Rembrandt’s Landscapes: Drawings and Prints. Exh. cat. National Gallery of Art, Washington. Boston, 1990: 105-106, fig. 90.

Broos, Ben P. J., ed. Great Dutch Paintings from America. Exh. cat. Royal Picture Gallery Mauritshuis, The Hague; Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco. The Hague and Zwolle, 1990: 42, 419-423, no. 59, color repro. 421.

1991

Kopper, Philip. America's National Gallery of Art: A Gift to the Nation. New York, 1991: 195, color repro.

1992

National Gallery of Art. National Gallery of Art, Washington. New York, 1992: 135, repro.

1995

Wheelock, Arthur K., Jr. Dutch Paintings of the Seventeenth Century. The Collections of the National Gallery of Art Systematic Catalogue. Washington, 1995: 364-369, color repro. 365.

1996

Chapman, H. Perry, Wouter Th. Kloek, and Arthur K. Wheelock, Jr. Jan Steen, painter and storyteller. Edited by Guido Jansen. Exh. cat. National Gallery of Art, Washington; Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam. Washington, 1996: no. 20, repro.

Hertel, Christiane. Vermeer: Reception and Interpretation. Cambridge, 1996: 24, fig. 6.

1997

Palmer, Michael, and E. Melanie Gifford. "Jan Steen's Painting Practice: The Dancing Couple in the Context of the Artist's Career." _Studies in the History of Art _ 57 (1997): 127-155, repro. no. 1.

Westermann, Mariët. The amusements of Jan Steen: comic painting in the seventeenth century. Studies in Netherlandish art and cultural history 1. Zwolle, 1997: 221-223, fig. 128.

2003

Waagen, Gustav Friedrich. Treasures of Art in Great Britain. Translated by Elizabeth Rigby Eastlake. Facsimile edition of London 1854. London, 2003: 2:118.

2004

Hand, John Oliver. National Gallery of Art: Master Paintings from the Collection. Washington and New York, 2004: 211, no. 168, color repro.

2005

Kloek, Wouter Th. Jan Steen (1626-1679). Rijksmuseum dossiers. Zwolle, 2005: 55-57, fig. 50.

2007

Sotheby's. "Old Master Paintings Evening Sale." London, 4 July 2007: no. 36, 114-119, figs. 1-2.

2014

Wheelock, Arthur K, Jr. "The Evolution of the Dutch Painting Collection." National Gallery of Art Bulletin no. 50 (Spring 2014): 2-19, repro.

Inscriptions

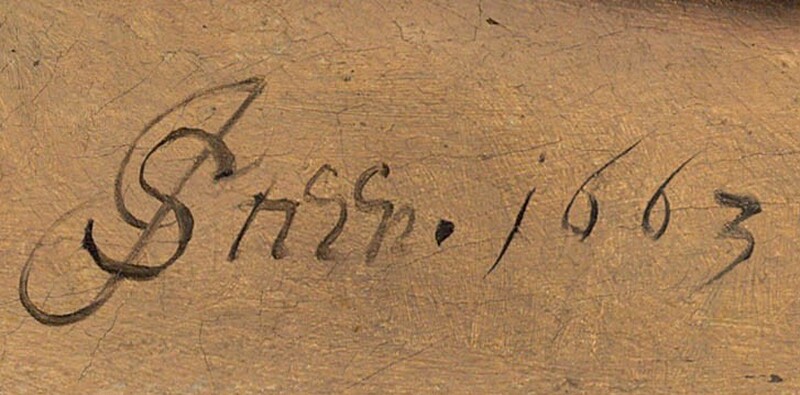

lower left, JS in ligature: JSteen. 1663

Wikidata ID

Q20177586