Philemon and Baucis

1658

Rembrandt van Rijn

Artist, Dutch, 1606 - 1669

After learning the fundamentals of drawing and painting in his native Leiden, Rembrandt van Rijn went to Amsterdam in 1624 to study for six months with Pieter Lastman (1583–1633), a famous history painter. Upon completion of his training Rembrandt returned to Leiden. Around 1632 he moved to Amsterdam, quickly establishing himself as the town’s leading artist. He received many commissions for portraits and attracted a number of students who came to learn his method of painting.

The Roman poet Ovid’s Metamorphoses provided Dutch artists with a wide range of mythological subjects, most of which contain underlying moralizing messages on human behavior. Rembrandt here depicts the moment when Jupiter and Mercury quietly reveal themselves to the elderly couple Philemon and Baucis, as described in the eighth book of Ovid’s commentaries. Rembrandt, who was able to penetrate the essence of the myth as no artist ever had, silhouetted Mercury against the primary light source to enhance the inherent drama of the moment.

The moral of the story is that hospitality and openness to strangers are virtues that are always rewarded. As depicted by Rembrandt, the hosts Philemon and Baucis, who come to recognize that they are in the presence of gods when the food and wine keep replenishing themselves, try to catch their only goose so they can offer their divine guests better fare. Jupiter commands them not to kill the goose and blesses their sparse offering with a firm yet comforting gesture. Dressed in exotic and loosely draped robes, Jupiter dominates the scene and takes on a Christ-like appearance that strongly echoes the Christ from Leonardo da Vinci’s Last Supper, which Rembrandt knew from a print. Leonardo’s composition had a profound impact on Rembrandt, and he used it in conceiving of a number of different subjects in prints, drawings, and paintings.

West Building Main Floor, Gallery 51

Artwork overview

-

Medium

oil on panel transferred to panel

-

Credit Line

-

Dimensions

overall: 54.5 x 68.5 cm (21 7/16 x 26 15/16 in.)

framed: 81.3 x 95.9 x 8.3 cm (32 x 37 3/4 x 3 1/4 in.) -

Accession Number

1942.9.65

More About this Artwork

Artwork history & notes

Provenance

Captain William Baillie [1723-1792], London; (his sale, Langford & Son, London, 1-2 February 1771, 2nd day, no. 73). possibly English private collection, by 1772.[1] Major Stanton; (Earl of Essex sale, Christie & Ansell, London, 31 January-1 February 1777, 2nd day, no. 75); Moris.[2] (Charles Sedelmeyer, Paris); Charles T. Yerkes, Jr. [1837-1905], Chicago and New York, by 1893;[3] (his sale, American Art Association, New York, 5-8 April 1910, no. 1160); (Scott and Fowles, New York); Otto H. Kahn [1867-1934], New York, by 1914 until at least April 1922; sold 1922, perhaps through (Scott and Fowles, New York) to Joseph E. Widener, Elkins Park, Pennsylvania;[4] inheritance from Estate of Peter A.B. Widener by gift through power of appointment of Joseph E. Widener, Elkins Park, Pennsylvania, after purchase by funds of the estate; gift 1942 to NGA.

[1] A mezzotint of the composition was executed in 1772 by Thomas Watson (John Charrington, A Catalogue of the Mezzotints After, or Said to Be After, Rembrandt, Cambridge, 1923:151, no. 182).

[2] The title page of the 1777 sale catalogue describes the collection as that of the Earl of Essex; however, in a copy of the catalogue at Christie's, London, the consignor's name is written in the margin as "Maj. Stanton." A handwritten results sheet bound into the same volume gives the following result: "75. 32/11/- Moris."

[3] Catalogue from Collection of Charles T. Yerkes, Chicago, U.S.A.. Chicago, 1893: no. 45.

[4] American Art News (9 December 1922):1 reported that the seller of the picture to Widener was Scott and Fowles. However, the journal also reported that Scott and Fowles had owned the painting since 1910, and various other sources, including Cornelis Hofstede de Groot, A Catalogue Raisonné of the Works of the Most Eminent Dutch Painters of the Seventeenth Century..., 8 vols., London, 1907-1927: 6:141, indicate that the owner during the mid-1910s was Otto H. Kahn. In addition, Kahn lent the painting to exhibitions in both 1920 and 1922, the latter a Rembrandt exhibition at the Fogg Art Museum, and although no checklist or catalogue exists for this exhibition, the museum’s records show that the picture entered the museum on 26 March 1922, and left on 13 April 1922. Perhaps Scott and Fowles simply handled the sale for Kahn.

Associated Names

Exhibition History

1920

Fiftieth Anniversary Exhibition, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 1920, unnumbered catalogue.

1922

Rembrandt Paintings, Drawings and Etchings, Fogg Art Museum, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1922, no catalogue.

1969

Rembrandt in the National Gallery of Art [Commemorating the Tercentenary of the Artist's Death], National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., 1969, no. 18, repro.

1998

A Collector's Cabinet, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., 1998, no. 47.

2000

Greek Gods and Heroes in the Age of Rubens and Rembrandt, National Gallery and Alexandros Soutzos Museum, Athens; Dordrechts Museum, 2000-2001, no. 62, repro.

2004

Rembrandt, Albertina, Vienna, 2004, no. 133, repro.

2011

Rembrandt in America, North Carolina Museum of Art, Raleigh; Cleveland Museum of Art; Minneapolis Institute of Arts, 2011-2012, no. 46, pl. 41.

Bibliography

n.d.

Catalogue from Collection of Charles T. Yerkes, Chicago, U.S.A.. Chicago, undated: no. 23.

1829

Smith, John. A Catalogue Raisonné of the Works of the Most Eminent Dutch, Flemish and French Painters. 9 vols. London, 1829-1842: 7(1836):79-80, no. 194.

1877

Vosmaer, Carel. Rembrandt Harmens van Rijn: sa vie et ses oeuvres. 2nd ed. The Hague, 1877: 252-253.

1885

Dutuit, Eugène. Tableaux et dessins de Rembrandt: catalogue historique et descriptif; supplément à l'Oeuvre complet de Rembrandt. Paris, 1885: 58, no. 111.

1886

Wurzbach, Alfred von. Rembrandtgalerie. Stuttgart, 1886: 97, no. 493.

1893

Catalogue from Collection of Charles T. Yerkes, Chicago, U.S.A.. Chicago, 1893: no. 45.

Michel, Émile. Rembrandt: Sa vie, son oeuvre et son temps. Paris, 1893: 446-447, 561.

1894

Michel, Émile. Rembrandt: His Life, His Work, and His Time. 2 vols. Translated by Florence Simmonds. New York, 1894: 2:128-129, 248.

1895

Stephens, F.G. "Mr. Yerkes' Collection at Chicago: The Old Masters." The Magazine of Art 18 (1895): 99.

1897

Bode, Wilhelm von, and Cornelis Hofstede de Groot. The Complete Work of Rembrandt. 8 vols. Translated by Florence Simmonds. Paris, 1897-1906: 6:6, 46, no. 407, repro.

1898

Sedelmeyer, Charles. Illustrated Catalogue of 300 Paintings by Old Masters of the Dutch, Flemish, Italian, French, and English schools, being some of the principal pictures which have at various time formed part of the Sedelmeyer Gallery. Paris, 1898: no. 137.

1899

Bell, Malcolm. Rembrandt van Rijn and His Work. London, 1899: 82, 184.

1904

Rosenberg, Adolf. Rembrandt: des Meisters Gemälde. Klassiker der Kunst in Gesamtausgaben 2. Stuttgart, 1904: 325, 404, repro.

Yerkes, Charles Tyson. Catalogue of paintings and sculpture in the collection of Charles T. Yerkes Esq., New York. 2 vols. New York (photogravures by Elson & Co., Boston), 1904: 1:no. 81, repro.

1905

Valentiner, Wilhelm R. Rembrandt und seine Umgebung. Strasbourg, 1905: 97.

1906

Valentiner, Wilhelm R. "Rembrandt auf der Lateinschule." Jahrbuch der Königlich Preussischen Kunstsammlungen 27 (1906): 118-128.

Rosenberg, Adolf. Rembrandt, des Meisters Gemälde. Klassiker der Kunst in Gesamtausgaben 2. 2nd ed. Stuttgart, 1906: repro. 325, 404.

1907

Brown, Gerard Baldwin. Rembrandt: A Study of His Life and Work. London, 1907: 138, 211.

Hofstede de Groot, Cornelis. A Catalogue Raisonné of the Works of the Most Eminent Dutch Painters of the Seventeenth Century. 8 vols. Translated by Edward G. Hawke. London, 1907-1927: 6(1916):140-141, no. 212.

Bell, Malcolm. Rembrandt van Rijn. The great masters in painting and sculpture. London, 1907: 79, 156.

Rosenberg, Adolf. The Work of Rembrandt, reproduced in over five hundred illustrations. Classics in Art 2. New York, 1907: 325, repro.

Thieme, Ulrich, and Felix Becker, eds. Allgemeines Lexikon der bildenden Künstler von der Antike bis zur Gegenwart. 37 vols. Leipzig, 1907-1950: 29(1935):266.

1908

Rosenberg, Adolf. Rembrandt, des Meisters Gemälde. Klassiker der Kunst in Gesamtausgaben 2. 3rd ed. Stuttgart and Berlin, 1908: repro. 388, 562.

Freise, Kurt. "Rembrandt and Elsheimer." The Burlington Magazine 13 (April 1908): 38–39.

1909

Rosenberg, Adolf. Rembrandt: Des Meisters Gemälde. Edited by Wilhelm R. Valentiner. Klassiker der Kunst in Gesamtausgaben 2. Stuttgart and Leipzig, 1909: repro. 388, 562.

1913

Rosenberg, Adolf. The Work of Rembrandt, reproduced in over five hundred illustrations. Classics in Art 2. Edited by Wilhelm R. Valentiner. 2nd ed. New York, 1913: repro. 325.

1914

Valentiner, Wilhelm R. The Art of the Low Countries. Translated by Mrs. Schuyler Van Rensselaer. Garden City, NY, 1914: 140-141, 248, no. 76.

1920

The Metropolitan Museum of Art. The Metropolitan Museum of Art Fiftieth Anniversary Exhibition. Exh. cat. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 1920: 9.

1921

Rosenberg, Adolf. The Work of Rembrandt. Edited by Wilhelm R. Valentiner. Classics in Art 2. 3rd ed. New York, 1921: 388, repro.

1922

"Widener Purchases Famous Rembrandt." Art News 21 (9 December 1922): 1.

1923

Meldrum, David S. Rembrandt’s Painting, with an Essay on His Life and Work. New York, 1923: 202, pl. 404.

Paintings in the Collection of Joseph Widener at Lynnewood Hall. Intro. by Wilhelm R. Valentiner. Elkins Park, Pennsylvania, 1923: unpaginated, repro.

1925

Valentiner, Wilhelm R. Rembrandt, des Meisters Handzeichnungen. 2 vols. Klassiker der Kunst in Gesamtausgaben. Berlin, 1925–1934: 2(1934):407 (under nos. 607 and 608).

1929

Wilenski, Reginald Howard. An Introduction to Dutch Art. New York, 1929: 59-60.

1930

Borenius, Tancred. "The New Rembrandt." The Burlington Magazine 57 (August 1930): 53-59.

1931

Valentiner, Wilhelm R. Rembrandt Paintings in America. New York, 1931: no. 132, repro.

Paintings in the Collection of Joseph Widener at Lynnewood Hall. Intro. by Wilhelm R. Valentiner. Elkins Park, Pennsylvania, 1931: 68, repro.

1932

Rijckevorsel, J. L. A. A. M. van. "Rembrandt en de Traditie." Ph.D. diss., Rijksuniversiteit Nijmegen, 1932: 77-78, 80, repro.

1934

Stechow, Wolfgang. "Rembrandts Darstellungen des Emmausmahles." Zeitschrift für Kunstgeschichte 3 (1934): 329-341.

1935

Bredius, Abraham. Rembrandt Schilderijen, 630 Afbeeldingen. Utrecht, 1935: no. 481, repro.

Bredius, Abraham. Rembrandt Gemälde, 630 Abbildungen. Vienna, 1935: no. 481, repro.

1936

Bredius, Abraham. The Paintings of Rembrandt. New York, 1936: no. 481, repro.

1938

Waldmann, Emil. "Die Sammlung Widener." Pantheon 22 (November 1938): 342.

1941

Valentiner, Wilhelm R. "Jan van de Cappelle." The Art Quarterly 4 (Autumn 1941): 272-296.

Stechow, Wolfgang. "Recent Periodical Literature on 17th-Century Painting in the Netherlands and Germany." Art Bulletin 23 (September 1941): 225-231.

Kieser, Emil. "Über Rembrandts Verhältnis zur Antike." Zeitschrift für Kunstgeschichte 10 (1941/1942): 146-147, 160-161.

Stechow, Wolfgang. "The Myth of Philemon and Baucis in Art." _Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes _ 4 (January 1941): 103-113, fig. 28a.

1942

Bredius, Abraham. The Paintings of Rembrandt. 2 vols. Translated by John Byam Shaw. Oxford, 1942: 1:no. 481; 2:repro.

National Gallery of Art. Works of art from the Widener collection. Washington, 1942: 6.

1945

Wilenski, Reginald Howard. Dutch Painting. Revised ed. London, 1945: 62.

1948

Rosenberg, Jakob. Rembrandt. 2 vols. Cambridge, MA, 1948: 1:185.

National Gallery of Art. Paintings and Sculpture from the Widener Collection. Washington, 1948: 46, repro.

1954

Benesch, Otto. The Drawings of Rembrandt: A Critical and Chronological Catalogue. 6 vols. London, 1954-1957: 5(1957):277, no. 958; 6(1957):396, no. A76.

1959

National Gallery of Art. Paintings and Sculpture from the Widener Collection. Reprint. Washington, DC, 1959: 46, repro.

1960

Goldscheider, Ludwig. Rembrandt Paintings, Drawings and Etchings. London, 1960: 180, pls. 97, 98.

1963

Walker, John. National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. New York, 1963 (reprinted 1964 in French, German, and Spanish): 313, 342, repro.

1964

Rosenberg, Jakob. Rembrandt: Life and Work. Revised ed. Greenwich, Connecticut, 1964: 300.

Gantner, Joseph. Rembrandt und die Verwandlung klassicher Formen. Berlin, 1964: 157-159, pl. 48.

1965

National Gallery of Art. Summary Catalogue of European Paintings and Sculpture. Washington, 1965: 110.

1966

Bauch, Kurt. Rembrandt Gemälde. Berlin, 1966: 7, no. 106, repro.

1968

Gerson, Horst. Rembrandt Paintings. Amsterdam, 1968: 103, color repro., 108, 132, 155, 357, 364-365, no. 278, repro., 499.

National Gallery of Art. European Paintings and Sculpture, Illustrations. Washington, 1968: 98, repro.

1969

Kitson, Michael. Rembrandt. London, 1969: no. 37, color repro. (also 1982 ed.).

Bredius, Abraham. Rembrandt: The Complete Edition of the Paintings. Revised by Horst Gerson. 3rd ed. London, 1969: repro. 390, 595, no. 481.

National Gallery of Art. Rembrandt in the National Gallery of Art: Commemorating the tercentenary of the artist's death. Exh. cat. National Gallery of Art, Washington, 1969: 6, 28-29, no. 18, repro.

1975

National Gallery of Art. European paintings: An Illustrated Summary Catalogue. Washington, 1975: 288, repro.

Walker, John. National Gallery of Art, Washington. New York, 1975: 283, no. 376, color repro.

1977

Bolten, J., and H. Bolten-Rempt. The Hidden Rembrandt. Translated by Danielle Adkinson. Milan and Chicago, 1977: 145-147, 149-150, color repro.

1982

Kitson, Michael. Rembrandt. 2nd ed. Oxford, 1982: no. 37, color repro.

1984

Schwartz, Gary. Rembrandt: Zijn leven, zijn schilderijen. Maarssen, 1984: 323, 330, no. 373, repro.

Walker, John. National Gallery of Art, Washington. Rev. ed. New York, 1984: 283, no. 370, color repro.

1985

National Gallery of Art. European Paintings: An Illustrated Catalogue. Washington, 1985: 332, repro.

Schwartz, Gary. Rembrandt: His Life, His Paintings. New York, 1985: 323, 330, no. 373, repro.

1986

Sluijter, Eric Jan. "De "Heydensche Fabulen" in de Noordnederlandse schilderkunst circa 1560–1670: een proeve van beschrijving en interpretatie van schilderijen met verhalende onderwerpen uit de klassieke mythologie." Ph.D. dissertation, University of Leiden, 1986: 100.

Sutton, Peter C. A Guide to Dutch Art in America. Washington and Grand Rapids, 1986: 313.

Tümpel, Christian. Rembrandt. Translated by Jacques and Jean Duvernet, Léon Karlson, and Patrick Grilli. Paris, 1986: repro. 249, 422, no. A26.

1990

Chapman, H. Perry. Rembrandt's Self-Portraits: A Study in Seventeenth-Century Identity. Princeton, 1990: 91, no. 135, repro.

Liedtke, Walter A. "Dutch Paintings in America: The Collectors and their Ideals." In Great Dutch Paintings from America. Edited by Ben P.J. Broos. Exh. cat. Royal Picture Gallery Mauritshuis, The Hague; Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco. The Hague and Zwolle, 1990: 43 fig. 30.

1991

Sello, Gottfried. "Beim Wein verrieten sich die Götter." Art Das Kunstmagazin 1 (January 1991): 82-88, repro.

1995

Wheelock, Arthur K., Jr. Dutch Paintings of the Seventeenth Century. The Collections of the National Gallery of Art Systematic Catalogue. Washington, 1995: 247-252, color repro. 249.

1998

Wheelock, Arthur K., Jr. A Collector's Cabinet. Exh. cat. National Gallery of Art, Washington, 1998: 67, no. 47.

2000

Paarlberg, Sander, and Peter Schoon. Greek gods and heroes in the age of Rubens and Rembrandt. Exh. cat. National Gallery/Alexandros Soutzos Museum and the Netherlands Institute, Athens; Dordrechts Museum, Dordrecht. Athens, 2000: no. 62, repro.

Wright, Christopher. Rembrandt. Collection Les Phares 10. Translated by Paul Alexandre. Paris, 2000: 74, fig. 58.

2002

Tromans, Nicholas. David Wilkie: painter of everyday life. Exh. cat. Dulwich Picture Gallery, London, 2002: 38, fig. 21.

Quodbach, Esmée. "The Last of the American Versailles: The Widener Collection at Lynnewood Hall." Simiolus 29, no. 1/2 (2002): 84, 96.

2003

Golahny, Amy. Rembrandt's Reading: The Artist's Bookshelf of Ancient Poetry and History. Amsterdam, 2003: 225-226, fig. 63..

2004

Schröder, Klaus Albrecht, and Marian Bisanz Prakken. Rembrandt. Edition Minerva. Exh. cat. Graphische Sammlung Albertina, Vienna. Wolfratshausen, 2004: 282, no. 133, repro.

2006

Schwartz, Gary. The Rembrandt Book. New York, 2006: 340, fig. 602.

2011

Keyes, George S., Tom Rassieur, and Dennis P. Weller. Rembrandt in America: collecting and connoisseurship. Exh. cat. North Carolina Museum of Art, Raleigh; Cleveland Museum of Art; Minneapolis Institute of Arts. New York, 2011: no. 46, pl. 41, 23, 70, 148-150, 157, 198.

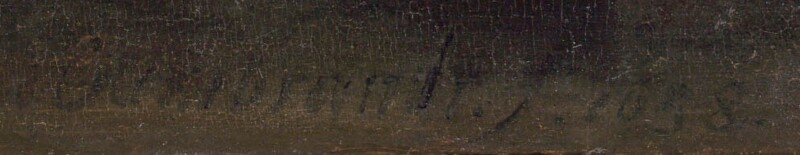

Inscriptions

lower left: Rembrandt f. 1658

Wikidata ID

Q20177472