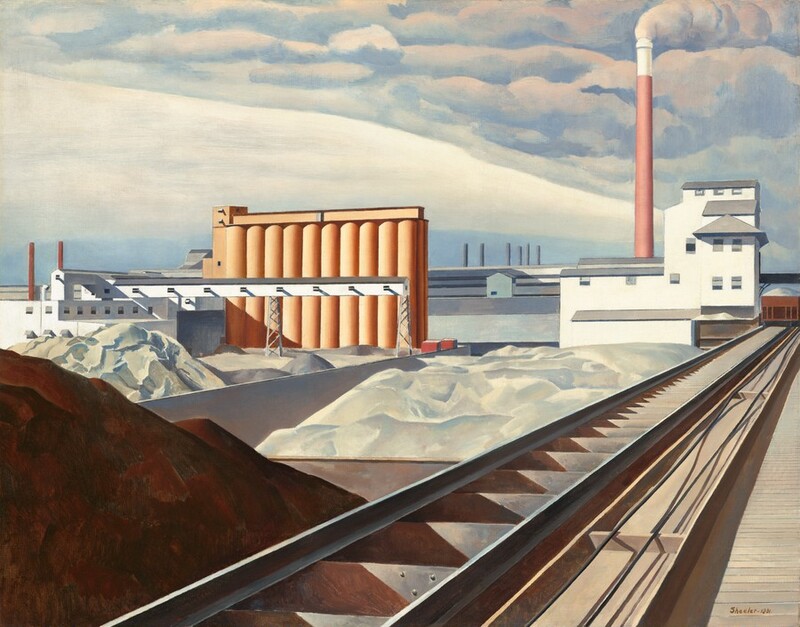

Classic Landscape

1931

Charles Sheeler

Painter, American, 1883 - 1965

Charles Sheeler was a master of both painting and photography, and his work in one medium influenced and shaped his work in the other.[1] In 1927, he was commissioned to photograph the Ford Motor Company's new River Rouge Plant near Detroit. Then the world's largest industrial complex, employing more than 75,000 workers, the plant produced Ford's Model A, successor to the famed Model T. Sheeler's photographs were used for the company's advertising, but he found himself greatly inspired by the subject, which he declared "incomparably the most thrilling I have had to work with."[2] In 1930, he began painting oils of the plant, creating over the next six years American Landscape (1930, The Museum of Modern Art, New York), Classic Landscape (1931), River Rouge Plant (1932, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York), and City Interior (1936, Worcester Art Museum, Worcester, MA).

Classic Landscape depicts an area of the plant where cement was made from by-products of the car manufacturing process. The silos in the middle distance stored the cement until it could be shipped for sale. Sheeler's choice of this relatively anonymous scene, rather than one connected with the production of automobiles, suggests that his interest lay in making a generalized portrait of the landscape of industry. That, in part, may explain his use in the painting's title of the word "classic," with its connotations of typical or standard. But "classic" also evokes the culture of ancient Greece and Rome, and Sheeler certainly implies that this modern American scene can be compared to the high achievements of the classical past. One might well be reminded of classical architecture by the temple-like form of the silos and the pediment-like roofs of the nearby buildings, but the matter clearly went beyond superficial resemblance. Like others of his day, Sheeler admired architecture that was functional and straightforward, with shape and plan determined by specifics of use rather than by conventions of style and decoration. For the great French architect Le Corbusier, whose influential Towards a New Architecture Sheeler probably read around the same time he was photographing the Rouge plant, the timeless principles of good design embodied by ancient architecture were indeed still at work in "the American grain elevators and factories, the magnificent first-fruits of the new age."[3] The iconic power and special importance of Classic Landscape were recognized from the time of its first public exhibition in New York in 1931. Through the years, it has become one of the most widely exhibited and best-known works of its era, and today it stands as a key masterwork of 20th-century American art.

[1] This overview is adapted from text previously published in Art for the Nation: Collecting for a New Century (Washington, DC, 2000).

[2] Letter to Walter Arensberg, Oct. 25, 1927; quoted in Theodore E. Stebbins Jr. and Norman Keyes Jr., Charles Sheeler: The Photographs (Boston, 1987), 25.

[3] Le Corbusier, Towards a New Architecture, trans. Frederick Etchells (London, 1927), 21.

East Building Ground Level, Gallery 106-C

Artwork overview

-

Medium

oil on canvas

-

Credit Line

-

Dimensions

overall: 63.5 x 81.9 cm (25 x 32 1/4 in.)

framed: 72.9 x 91.1 x 7 cm (28 11/16 x 35 7/8 x 2 3/4 in.) -

Accession Number

2000.39.2

More About this Artwork

Artwork history & notes

Provenance

Acquired 1931 from the artist by (The Downtown Gallery, New York); purchased 1932 by Edsel B. Ford [d. 1943], Dearborn, Michigan; by inheritance to his wife, Mrs. Edsel B. Ford [d. 1976], Grosse Point Shores, Michigan; her estate; by transfer 1982 to the Edsel and Eleanor Ford House, Detroit; (sale, Sotheby's, New York, 2 June 1983, no. 201); (Hirshl & Adler Galleries, New York; Kennedy Gallery, New York; Long & Company Gallery, Houston); purchased 4 June 1984 by Mr. and Mrs. Barney A. Ebsworth, St. Louis; gift 2000 to NGA.

Associated Names

Exhibition History

1931

Charles Sheeler, Exhibition of Recent Works, The Downtown Gallery, New York, 1931, checklist no. 4.

1932

Paintings and Drawings by Charles Sheeler, The Arts Club of Chicago, January-February 1932, no. 3.

American Painting & Sculpture, 1862-1932, Museum of Modern Art, New York, 1932-1933, no. 95, repro.

American Contemporary Paintings and Sculpture, The Society of Arts and Crafts, Detroit, March-April 1932, no. 26.

1933

A Loan Exhibition of Retrospective American Painting, The Society of Arts and Crafts, Detroit, 1933, typewritten checklist, no. 13.

1934

Water Colours and Drawings by Sheeler, Hopper and Burchfield, Fogg Art Museum, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1934, no catalogue.

1935

An Exhibition of Paintings by Charles Burchfield and Charles Sheeler, The Society of Arts and Crafts, Detroit, 1935, no. 17.

1938

Trois Siècles d'Art au Etats-Unis, Musée de Jeu de Paume, Paris, May-July 1938, no. 154, fig. 35.

Americans at Home: 32 Painters and Sculptors, The Downtown Gallery, New York, October 1938, no. 25.

1939

Charles Sheeler: Paintings, Drawings, and Photographs, Museum of Modern Art, New York, October-November 1939, no. 22, repro.

Art in Our Time: An Exhibition to Celebrate the Tenth Anniversary of the Museum of Modern Art and the Opening of its New Building, Museum of Modern Art, New York, April 1939, no. 140, repro.

1946

American Painting from the Eighteenth Century to the Present Day, Tate Gallery, London, 1946, no. 192.

1953

An Exhibition of Contemporary Art Collected by American Business, Meta Mold Aluminium Company, Cedarburg, Wisconsin, 1953, no. 40, repro. (incorrectly listed as owned by Henry Ford II).

1954

Charles Sheeler: A Retrospective Exhibition, Art Galleries, University of California, Los Angeles; M.H. DeYoung Memorial Museum, San Franisco; Fort Worth Art Center; Munson-Williams-Proctor Institute, Utica; Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Philadelphia; San Diego Fine Arts Gallery, 1954, no. 15.

Ben Shahn, Charles Sheeler, Joe Jones, Detroit Institute of Arts, March-April 1954, no. 7, as Classical Landscape, incorrectly dated 1932.

1957

Painting in America: The Story of 450 Years, Detroit Institute of Arts, 1957, no. 164, fig. 161, as Modern Classic.

1958

The Iron Horse in Art: The Railroad as It Has Been Interpreted by Artists of the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries, Fort Worth Art Center, 1958, no. 96, fig. 24.

1960

The Precisionist View in American Art, Walker Art Center, Minneapolis; Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; Detroit Institute of Arts; Los Angeles County Museum of Art; San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, 1960-1961, unnumbered catalogue.

1963

The Quest of Charles Sheeler, 83 Works Honoring His 80th Year, University of Iowa, Iowa City, 1963, no. 37, fig. 10.

1966

Art of the United States: 1670-1966, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, 1966, no. 255, repro.

1967

Charles Sheeler, A Retrospective Exhibition, Cedar Rapids Art Center, 1967, no. 9, repro.

1968

Charles Sheeler, National Collection of Fine Arts (now National Museum of American Art), Washington, D.C.; Philadelphia Museum of Art; Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, 1968-1969, no. 63, repro.

1969

Detroit Collects, Selections from the Collections of the Friends of Modern Art, Detroit Institute of Arts, 1969, no. 168, as Classic Landscape--River Rouge.

1976

Arts and Crafts in Detroit 1906-1976: The Movement, The Society, The School, Detroit Institute of Arts, 1976-1977, no. 239, repro. (incorrectly dated 1932).

1977

The Modern Spirit: American Painting 1908-1935, Royal Scottish Academy, Edinburgh; Hayward Gallery, London, 1977, no. 101, repro.

Lines of Power, Hirschl & Adler Galleries, New York, 1977, unnumbered catalogue, repro.

1978

William Carlos Williams and the American Scene, 1920-1940, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, 1978-1979, unnumbered catalogue, repro.

The Rouge: The Image of Industry in the Art of Charles Sheeler and Diego Rivera, Detroit Institute of Arts, 1978, no. 27, repro.

1979

2 Jahrzehnte Amerikanische Malerei, 1920-1940, Städtische Kunsthalle, Düsseldorf; Kunsthaus, Zurich; Palais des Beaux-Arts, Brussels, 1979, no. 78, repro.

1980

Paris and the American Avant-Garde, 1900-1925, Kalamazoo Institute of Arts; Jesse Besser Museum, Alpena, Michigan; University of Michigan Museum of Art, Ann Arbor; Krasl Art Center, St. Joseph, Michigan; Kresge Art Center Gallery, East Lansing; Ella Sharp Museum, Jackson, Michigan, 1980, no. 30.

1984

The Art of Collecting, Hirschl & Adler Galleries, New York, 1984, no. 44, repro.

1986

The Machine Age in America, 1918-1941, Brooklyn Museum; Carnegie Institute, Pittsburgh; Los Angeles County Museum of Art; High Museum of Art, Atlanta, 1986-1988, not in catalogue (shown only in Brooklyn and Pittsburgh).

1987

The Ebsworth Collection: American Modernism, 1911-1947, Saint Louis Art Museum; Honolulu Academy of Arts; Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, 1987-1988, no. 61, repro.

Charles Sheeler: Paintings, Drawings, Photographs, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; Museum of Fine Arts, Dallas, 1987-1988, no. 37, repro. (shown only in Boston and Dallas).

1991

The 1920s: Age of the Metropolis, Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, 1991, no. 590, fig. 608.

1993

American Impressions: Masterworks from American Art Forum Collections, 1875-1935, National Museum of American Art, Washington, D.C., March-July 1993, no catalogue.

American Art in the 20th Century: Painting and Sculpture 1913-1993, Martin-Gropius-Bau, Berlin; Royal Academy of Arts, London, September-December 1993, no. 54, repro. (shown only in London).

1994

Precisionism in America 1915-1941: Reordering Reality, Montclair Art Museum, New Jersey; Norton Gallery of Art, West Palm Beach; Columbus Museum of Art, Ohio; Sheldon Memorial Art Gallery, Lincoln, Nebraska, 1994-1995, no. 65.

1999

The American Century: Art and Culture, 1900-1950, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, 1999, fig. 292.

2000

Art for the Nation: Collecting for a New Century, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., 2000-2001, unnumbered catalogue, repro.

Twentieth-Century American Art: The Ebsworth Collection, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.; Seattle Art Museum, 2000, no. 58, repro.

2006

Charles Sheeler: Across Media, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.; Art Institute of Chicago; Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, M.H. de Young Memorial Museum, 2006-2007, no. 27, repro.

2009

After Many Springs: Regionalism, Modernism, and the Midwest, Des Moines Art Center; St. Louis Art Museum, 2009, pl. 3 (shown only in Des Moines).

2015

Picturing the Americas: Landscape Painting from Tierra del Fuego to the Arctic, Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto; Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, Bentonville; Pinacoteca do Estado de Sao Paulo, 2015-1016, unnumbered catalogue, fig. 3 (shown only in Toronto and Bentonville).

2016

America After the Fall: Painting in the 1930s, Art Institute of Chicago; Musée de l'Orangerie, Paris; Royal Academy of Arts, London, 2016-2017, no. 44, repro. (shown only in Chicago), no. 44.

2018

Konstruktion der Welt: Kunst und Okonomie, 1919-1939 [Constructing the World: Art and Economy 1919-1939], Kunsthalle Mannheim, 2018-2019, unnumbered catalogue, repro.

Cult of the Machine: Precisionism and American Art, Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, de Young Museum; Dallas Museum of Art, 2018-2019, no. 35, repro. (shown only in San Francisco, 2018).

2019

Life is a Highway: Art and American Car Culture, Toledo Museum of Art, 2019, no.27, repro.

Bibliography

1931

"Exhibition in New York: Charles Sheeler, Downtown Gallery." Art News 30, no. 8 (1931): 8.

Devree, Howard V. "Charles Sheeler's Exhibition." New York Times (19 November 1931): 32, col. 6.

Kootz, Samuel M. "Ford Plant Photos of Charles Sheeler." Creative Art 8, no. 4 (April 1931): 99, repro.

McCormick, W.B. "Machine Age Debunked." New York American (26 November 1931): 19, col. 2 (also printed in Los Angeles Examiner, 9 December 1931).

Pemberton, Murdock. "The Art Galleries: The Strange Case of Charles Sheeler." The New Yorker 7 (28 November 1931): 48.

Charles Sheeler, Exhibition of Recent Works. Exh. cat. The Downtown Gallery, New York, 1931: checklist no. 4.

1932

Brace, Ernest. "Charles Sheeler." Creative Art 11 (October 1932): 98, 104, repro.

Ringel, Frederick J., ed. America as Americans See It. New York, 1932: repro. facing 303.

American Contemporary Paintings and Sculpture. Exh. cat. The Society of Art and Crafts, Detroit, March-April 1932: no. 26.

American Painting and Sculpture, 1862-1932. Exh. cat. Museum of Modern Art, New York, 1932-1933: no. 95, repro.

Paintings and Drawings by Charles Sheeler. Exh. cat. The Arts Club of Chicago, Chicago, January-February 1932: no. 3.

1933

"New Phases of American Art." London Studio 5 (February 1933): 90, repro.

A Loan Exhibition of Retrospective American Painting. Exh. cat. The Society of Arts and Crafts, Detroit, 1933, typewritten checklist, no. 13.

1934

"Les Etats Unis." L'Amour d'Art 15 (November 1934): 467, fig. 606.

New York Times Book Review 82 (7 July 1934): 4, sec. 5, repro.

1935

"Loan Listings." Fogg Art Museum Annual Report. Cambridge, 1934-1935.

An Exhibition of Paintings by Charles Burchfield and Charles Sheeler. Exh. cat. The Society of Arts and Crafts, Detroit, 1935, no. 17.

1936

"Charles Sheeler--Painter and Photographer." The Index of Twentieth Century Artists 3, no. 4 (January 1936): 231.

1938

"New Exhibition of the Week: Works that were Shown Abroad." Art News 37, no. 5 (15 October 1938): 13.

Jewell, Edward Alden. "Art of Americans Put on Exhibition." New York Times (5 October 1938): col. 1, "Art."

Rourke, Constance. Charles Sheeler, Artist in the American Tradition. New York, 1938: 83, 147-148, 153, 166, 194, repro.

Sweeney, James J. "L'art Contemporain aux Etats-Unis." Cahiers d'art 13 (1938): 61, repro.

Whelan, Anne. "Barn Is Thing of Beauty to Charles Sheeler, Artist." The Bridgeport Sunday Post (21 August 1938): B4.

Americans at Home: 32 Painters and Sculptors. Exh. cat. The Downtown Gallery, New York, October 1938, no. 25.

Trois siècles d'art aux États-Unis: exposition organisée en collaboration avec le Museum of Modern Art, New-York. Exh. cat. Musée du Jeu de Paume, Paris, May-July 1938, no. 154, fig. 35.

1939

Bulletin of the Museum of Modern Art 6 (May-June 1939): 13, repro.

"Exhibits Work of Three Decades." The Villager (Greenwich Village) 7, no. 28 (12 October 1939): 7, col. 3.

"Museum of Modern Art to Open Its Fifth Show of a Living Artist's Works." New York Herald Tribune 99 (4 October 1939): 21, col. 2-3.

B., C. "Art of Charles Sheeler." The Christian Science Monitor 31 (14 October 1939): 12, col. 3.

Coates, Robert M. "The Art Galleries/A Sheeler Retrospective." The New Yorker 15 (14 October 1939): 55.

Cortissoz, Royal. "Types of American, British, and French Art." New York Herald Tribune 99, no. 33 (8 October 1939): 8, sec. VI, col. 1-5.

Crowninshield, Frank. "Charles Sheeler's 'Americana'." Vogue 94 (15 October 1939): 106.

Genauer, Emily. "Charles Sheeler in One-Man Show." New York World Telegram 82 (7 October 1939): 34, col. 1.

Jewell, Edward Alden. "Sheeler in Retrospect." New York Times (8 October 1939): 9, col. 3.

T., B. "The Home Forum." The Christian Science Monitor 31 (28 June 1939): 8, col. 2-5, repro.

Art in Our Time: An Exhibition to Celebrate the Tenth Anniversary of the Museum of Modern Art and the Opening of its New Building. Exh. cat. Museum of Modern Art, New York, April 1939, no. 140, repro.

Charles Sheeler: Paintings, Drawings, and Photographs. Introduction by William Carlos Williams. Exh. cat. Museum of Modern Art, New York, 1939, no. 22, repro.

1940

New York Times Book Review 89 (15 September 1940): 3, sec. 6, col. 3-5, repro.

Beam, Laura. "Development of the Artist/.../IV/Charles Sheeler." Manuscript, American Association of University Women, 1940: 23.

1946

American Painting from the Eighteenth Century to the Present Day. Exh. cat. Tate Gallery, London, 1946: no. 192.

1948

Born, Wolfgang. American Landscape Painting, An Interpretation. New Haven, 1948: xiii, 211, 213, fig. 142.

1953

"Cedarburg Shows Off Top Art." The Milwaukee Journal, Picture Journal (7 June 1953): 3, repro. (incorrectly listed as lent by Henry Ford II).

An Exhibition of Contemporary Art Collected by American Business. Exh. cat. Meta Mold Aluminum Company, Cedarburg, WI, 1953: no. 40, repro. (incorrectly listed as owned by Henry Ford II).

1954

Frankenstein, Alfred. "This World/The Charles Sheeler Exhibition." San Francisco Chronicle 18 (28 November 1954): 21, col. 1, magazine section.

Wight, Frederick S. "Charles Sheeler." Art in America 42, no. 3 (October 1954): 192, 197, repro.

Williams, William Carlos. "Postscript by a Poet." Art in America 42, no. 3 (October 1954): 215.

Ben Shahn, Charles Sheeler, Joe Jones, Detroit Institute of Arts. Exh. cat. Detroit Institute of Arts, Detroit, 1954: no. 7, as Classical Landscape, incorrectly dated 1932.

Charles Sheeler: A Retrospective Exhibition. Exh. cat. UCLA Art Galleries, Los Angeles; M.H. de Young Memorial Museum, San Francisco; Fort Worth Art Center; Munson-Williams-Proctor Arts Institute, Utica; Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Philadelphia; Fine Arts Gallery, San Diego. Los Angeles, 1954: no. 15.

1955

Chanin, A.L. "Charles Sheeler: Purist Brush and Camera Eye." Art News 54, no. 4 (Summer 1955): 72.

Kepes, Gyorgy. "The New Landscape in Art and Science." Art in America 43, no. 3 (October 1955): 35, repro.

Sorenson, George N. "Portraits of Machine Age: Sheeler Exhibition Called Year's Most Important." The San Diego Union (9 January 1955): repro.

1956

Richardson, Edgar P. "Three American Painters: Sheeler--Hopper--Burchfield." Perspectives USA (Summer 1956): following 112, repro.

Richardson, Edgar P. Painting in America: The Story of 450 Years. New York, 1956: fig. 161 (as Modern Classic).

1957

Freedman, Leonard, ed. Looking at Modern Painting. New York, 1957: 100-101, repro.

Wight, Frederick S. "Charles Sheeler." In New Art in America, Fifty Painters of the 20th Century. Greenwich, Connecticut, 1957: 97, 102, repro.

Painting in America: The Story of 150 Years. Exh. cat. Detroit Institute of Arts, Detroit, 1957: no. 164, fig. 161, as Modern Classic.

1958

The Iron Horse in Art: The Railroad as It Has Been Interpreted by Artists of the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries. Exh. cat. Fort Worth Art Center, Fort Worth, TX, 1958: no. 96, fig. 24.

1959

Craven, George M. "Sheeler at Seventy-Five." College Art Journal 18, no. 2 (Winter 1959): 138.

1960

The Precisionist View in American Art. Exh. cat. Walker Art Center, Minneapolis; Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; Detroit Institute of Arts, Detroit; Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles; San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, San Francisco. Minneapolis, 1960: n.p.

1963

Dochterman, Lillian N. "The Stylistic Development of the Work of Charles Sheeler." Ph.D. dissertation, University of Iowa, Iowa City, 1963: 49-50, 56, 58-60, 65, 320, no. 31.153, repro.

The Quest of Charles Sheeler: 83 Works Honoring His 80th Year. Exh. cat. University of Iowa, Iowa City, 1963: no. 37, fig. 10.

1965

Richardson, Edgar P. Painting in America from 1502 to the Present. New York, 1965: 341, repro. 377.

1966

Art of the United States: 1670-1966. Exh. cat. Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, 1966: no. 255, repro.

1967

The Artist in America. Compiled by the editors of Art in America. New York, 1967: 169.

Charles Sheeler: A Retrospective Exhibition. Exh. cat. Cedar Rapids Art Center, Cedar Rapids, IA, 1967: no. 9, repro.

1968

Charles Sheeler. Exh. cat. National Collection of Fine Arts (now National Museum of American Art), Washington; Philadelphia Museum of Art, Philadelphia; Whitney Museum of America Art, New York. Washington, DC, 1968: no. 63, repro.

1969

Selections from the Collections of the Friends of Modern Art. Exh. cat. Detroit Institute of Arts, Detroit, 1969: no. 168, as Classic Landscape--River Rouge.

1972

Hunter, Sam. American Art of the 20th Century. New York, 1972: 91, pl. 192.

1973

Bennet, Ian. A History of American Painting. London, 1973: 185.

1974

Davidson, Abraham A. The Story of American Painting. New York, 1974: 131-133, no. 118, repro.

1975

Friedman, Martin. Charles Sheeler: Paintings, Drawings, and Photographs. New York, 1975: 8, 95, 112-113, pl. 17.

1976

Silk, Gerald D. "The Image of the Automobile in Modern Art." Ph.D. dissertation, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, 1976: x, 114, 292, fig. 93.

Wilmerding, John. American Art. Hammondsworth, England, and New York, 1976: 181.

Arts and Crafts in Detroit 1906-1976: The Movement, The Society, The School. Exh. cat. Detroit Institute of Arts, Detroit, 1976: no. 239, repro. (incorrectly dated 1932).

1977

Maroney, James H. Lines of Power. Exh. cat. Hirschl & Adler Galleries, New York, 1977: n.p., repro.

Brown, Milton W. The Modern Spirit: American Painting, 1908-1935. Exh. cat. Royal Scottish Academy, Edinburgh; Hayward Gallery, London. London, 1977: no. 101, repro.

1978

Yeh, Susan Fillin. "Charles Sheeler's 1923 'Self-Portrait'." Arts 52, no. 5 (January 1978): 107.

Yeh, Susan Fillin. "The Rouge." Arts Magazine 53 (November 1978): 8, repro.

The Rouge: The Image of Industry in the Art of Charles Sheeler and Diego Rivera. Exh. cat. Detroit Institute of Arts, Detroit, 1978: no. 27, repro.

Tashjian, Dickran. William Carlos Williams and the American Scene, 1920-1940. Exh. cat. Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, 1978: n.p.

1979

Brown, Milton, et al. American Art: Painting, Sculpture, Architecture, Decorative Arts, and Photography. New York, 1979: 427, pl. 66.

Towle, Tony. "Art and Literature: William Carlos Williams and the American Scene." Art in America 67, no. 3 (May-June 1979): 52, repro.

Yeh, Susan Fillin. "Charles Sheeler's 'Upper Deck'." Arts 53, no. 5 (January 1979): 94.

2 Jahrzehnte amerikanische Malerei 1920-1940. Exh. cat. Städtische Kunsthalle, Düsseldorf; Kunsthaus, Zürich; Palais de Beaux-Arts, Brüssel. Düsseldorf, 1979: no. 78, repro.

Fellenberg, Walo von. "Griff nach der Realität." Weltkunst 49 (1979): 2555 repro.

1980

Les Realismes, 1919-1939. Exh. cat. Georges Pompidou Centre, Paris; Staatliche Kunsthalle, Berlin. Paris, 1980: 30, 36, repro.

Dintenfass, Terry. Charles Sheeler (1883-1965), Classic Themes: Paintings, Drawings, and Photographs. Exh. cat. Dintenfass Gallery, New York, 1980: 9.

Dozema, Marianne. American Realism in the Industrial Age. Exh. cat. Cleveland Museum of Art, 1980: fig. 16.

Sims, Patterson. Charles Sheeler, A Concentration of Works from the Permanent Collection of The Whitney Museum of American Art, a 50th Anniversary Exhibition. Exh. cat. Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, 1980: 24-25, repro.

Yeh, Susan Fillin. "Charles Sheeler, Industry, Fashion, and the Vanguard." Arts Magazine 54, no. 6 (February 1980): 158.

Paris and the American Avant-Garde, 1900-1925. Exh. cat. Kalamazoo Institute of Arts, Kalamazoo, MI; Jesse Besser Museum, Alpena, MI; University of Michigan Museum of Art, Ann Arbor, MI; Krasl Art Center, St Joseph, MI; Kresge Art Center Gallery, East Lansing; Ella Sharp Museum, Jackson, MI. Detroit, 1980: no. 30.

1981

Yeh, Susan Fillin. "Charles Sheeler and the Machine Age." Ph.D. dissertation, City University of New York, 1981: 42, 64-65, n. 126-132, 72-73, 95, 113, 145, 150, n. 31, 152, n. 57-58, 154, n. 84-85, 185-186, 189, 217, 222-224, 231, nn. 39 and 47, 296, pl. 44.

1982

Tsujimoto, Karen. Images of America: Precisionist Painting and Modern Photography. Exh. cat. San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, 1982: 83.

1983

"Choice Auctions." The Magazine Antiques 213 (June 1983): 23, repro.

Art at Auction: The Year at Sotheby's, 1982-1983, London, 1983: 10, 134, color repro.

Hogrefe, Jeffrey. "Sheeler Auctioned for $1.87 Million." Washington Post (3 June 1983).

Reif, Rita. "Sheeler Work Sets a Record." New York Times (3 June 1983).

Stewart, Patrick L. "Charles Sheeler, William Carlos Williams, and Precisionism: A Redefinition." Arts Magazine 58, no. 3 (November 1983): 100-114.

1984

International Auction Records. Editions Mayer 17 (1984): 1271, repro.

The Art of Collecting. Exh. cat. Hirschl & Adler Galleries, New York, 1984: no. 44, repro.

1986

Troyon, Carol. "The Open Window and the Empty Chair: Charles Sheeler's 'View of New York'." The American Art Journal 18, no. 2 (1986): 25.

Tepfer, Diane. "Twentieth Century Realism: The American Scene." In American Art Analog. Compiled by Michael David Zellman. New York, 1986: 743, 745, repro.

Wilson, Richard Guy, et al. The Machine Age in America, 1918-1941. Exh. cat. Brooklyn Museum, New York; Carnegie Institute, Pittsburgh; Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles; High Museum of Art, Atlanta. New York, 1986: not in catalogue.

1987

Colihan, J. "Industrial Landscape Paintings of Charles Sheeler." American Heritage 38, no. 7 (1987): 86-87, repro.

McQuade, Donald, ed. The Harper American Literature. New York, 1987: vol. 2, color repro.

Stebbins, Theodore E., and Norman Keyes, Jr. Charles Sheeler: The Photographs. Exh. cat. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, 1987: 34, 40.

Troyen, Carol, and Erica E. Hirshler. Charles Sheeler: Paintings and Drawings. Exh. cat. Museum of Fine Art, Boston; Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; Museum of Fine Arts, Dallas. Boston, 1987: no. 37, repro.

The Ebsworth Collection: American Modernism, 1911-1947. Exh. cat. Saint Louis Art Museum, Saint Louis; Honolulu Academy of Arts, Honolulu; Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Saint Louis, 1987: no. 61, repro.

1989

Lucic, Karen. "Charles Sheeler and Henry Ford: A Craft Heritage for the Machine Age." Bulletin of the Detroit Institute of Arts 65, no. 1 (1989): 38-39, 44-46, repro.

1990

Raymond Loewy: Pionier des Amerikanischen Industriedesigns. Exh. cat. Internationalen Design Zentrum, Berlin, 1990: 260, repro.

Rubin, Joan Shelley. "A Convergence of Vision: Constance Rourke, Charles Sheeler, and American Art." American Quarterly 42, no. 2 (June 1990): 209, 211, repro.

1991

Vetrocq, Marcia E. "Modernity and the City." Art in America (November 1991): 56.

Lucic, Karen. Charles Sheeler and the Cult of the Machine. Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1991: 13-14, 76, 98, 102-103, 107, 114, 117, 141, pl. 37.

Clair, Jean, ed. The 1920s: Age of the Metropolis. Exh. cat. Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, Montreal, 1991: no. 590, fig. 608.

1992

Harnsberger, R. Scott. Ten Precisionist Artists: Annotated Bibliographies. Westport, Connecticut, 1992: 230, 263, 264.

1993

"American Art: Odd Ommissions." The Economist (25 September 1993): 102, repro.

Livingston, M. "American Art in the Twentieth Century: Painting and Sculpture, 1913-1993." The Burlington Magazine 135 (September 1993): 646, repro.

Joachimides, Christos M., and Norman Rosenthal, eds. American Art in the 20th Century: Painting and Sculpture 1913-1993. Exh. cat. Martin-Gropius-Bau, Berlin; Royal Academy of Arts, London. Munich, 1993: no. 54, repro.

1994

Precisionism in America, 1915-1941: Reordering Reality. Exh. cat. Montclair Museum of Art, Montclair; Norton Gallery of Art, West Palm Beach; Columbus Museum of Art, Columbus; Sheldon Memorial Art Gallery, Lincoln. New York, 1994: no. 65.

1995

Roberts, Brady M., James M. Dennis et al. Grant Wood: An American Artist Revealed. Exh. cat. Joslyn Art Museum, Omaha, NE; Davenport Museum of Art, IA, and the Worcester Art Museum, MA, 1995-1996. Davenport and San Francisco, 1995: 23, repro.

Stavitsky, Gail. "Precisionism in America, 1915-1941: Reordering Reality." American Art Review 7, no. 1 (February-March 1995): 125, repro.

Zimmer, Michael. "The Many Layers of Precisionism." New York Times (11 December 1995): repro.

1996

Fontenas, Hugues. "Un Trouble de L'Esthetique Architectural." Cahiers du Musée National d'Art Moderne 58 (Winter 1996): 97, repro.

1998

Dennis, James M. Renegade Regionalists: The Modern Independence of Grant Wood, Thomas Hart Benton, and John Steuart Curry. Madison, 1998: 221-224, 231, repro.

1999

Maroney, Jr., James H. "Charles Sheeler Reveals the Machinery of His Soul." American Art 13, no. 2 (Summer 1999): 49.

Haskell, Barbara. The American Century: Art and Culture, 1900–1950. Exh. cat. Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, 1999: fig. 292.

Hughes, Robert. "A Nation's Self." Time (10 May 1999): 78-79, repro. [exhibition review]

2000

Art for the Nation: Collecting for a New Century. Exh. cat. National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., 2000: 104 repro., 105.

Robertson, Bruce. Twentieth-Century American Art: The Ebsworth Collection. Exh. cat. National Gallery of Art, Washingtion; Seattle Art Museum, Seattle. Washington, D.C., 2000: no. 58, repro.

2004

Hand, John Oliver. National Gallery of Art: Master Paintings from the Collection. Washington and New York, 2004: 420-421, no. 353, color repro.

2006

Brock, Charles. Charles Sheeler: Across Media. Exh. cat. National Gallery of Art, Washington; The Art Institute of Chicago; Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco; M.H. de Young Memorial Museum, San Francisco. Washington and Berkeley, 2006: no. 27, repro.

2008

Miller, Angela et al. American Encounters: Art, History, and Cultural Identity. Upper Saddle River, NJ, 2008: 463-464, color fig. 14.17

2009

Balken, Debra Bricker. After Many Springs: Regionalism, Modernism, and the Midwest. Exh. cat. Des Moines Art Center, Des Moines. New Haven, 2009: pl. 3.

2012

Brock, Charles. “George Bellows: An Unfinished Life.” In George Bellows ed. Charles Brock. Exh. cat. National Gallery of Art, Washington; Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; Royal Academy of Arts, London. Munich, 2012: 25-24, color fig. 16.

2015

Brownlee, Peter John, Valeria Piccoli, and Georgiana Uhlyarik, eds. Picturing the Americas: Landscape Painting from Tierra del Fuego to the Arctic. Exh. cat. Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto; Crystal Bridge Museum of American Art, Bentonville; Pinacoteca do Estado de Sao Paolo, 2015-2016. Chicago and New Haven: 2015: 191.

2016

National Gallery of Art. Highlights from the National Gallery of Art, Washington. Washington, 2016: 297, repro.

Barter, Judith A., ed. American After the Fall: Painting in the 1930s. Exh. cat. Art Institute of Chicago; Musee de l'Orangerie, Paris; Royal Academy of Arts, London, 2016-2017. Chicago, 2016: no. 44, 20, repro. 21, 31, 65.

Inscriptions

lower right: Sheeler-1931.

Wikidata ID

Q20192851