Head of an Aged Woman

1655/1660

Rembrandt Workshop

Painter

Related Artist, Dutch, 1606 - 1669

After learning the fundamentals of drawing and painting in his native Leiden, Rembrandt van Rijn went to Amsterdam in 1624 to study for six months with Pieter Lastman (1583–1633), a famous history painter. Upon completion of his training Rembrandt returned to Leiden. Around 1632 he moved to Amsterdam, quickly establishing himself as the town’s leading artist, specializing in history paintings and portraiture. He received many commissions and attracted a number of students who came to learn his method of painting.

Rembrandt and members of his workshop frequently painted tronies, informal bust-length figure studies that were not considered to be portraits. The large number of such studies that have survived from Rembrandt's workshop indicates that the creation of tronies was one way by which the master taught his manner of painting. In this small tronie, an old woman stares out from under a white headpiece, her black cape fastened at the neck. Rembrandt's paintings of old women from the mid-1650s served as models for the student who created this particular panel. Abraham van Dijck (1635/1636–1672), who seems to have studied with Rembrandt in the early 1650s, is the most likely artist of this painting. The same model appears in several other of Van Dijck’s works, in particular his The Old Prophetess, c. 1655–1660, now in the Hermitage.

Artwork overview

-

Medium

oil on panel

-

Credit Line

-

Dimensions

overall: 21.1 x 17.5 cm (8 5/16 x 6 7/8 in.)

-

Accession Number

1942.9.64

More About this Artwork

Artwork history & notes

Provenance

Probably H. Verschuring, The Hague, by 1751. Gottfried Winkler [1731-1795], Leipzig, by 1765.[1] Possibly with (Stéphane Bourgeois [Bourgeois Frères], Paris), in 1893/1894.[2] Rodolphe Kann [1845-1905], Paris, by 1898;[3] purchased 1907 with the entire Kann collection by (Duveen Brothers, Inc., London, New York, and Paris);[4] sold to (F. Kleinberger & Co., Paris);[5] by exchange to (Leo Nardus [1868-1955], Suresnes, France, and New York); by exchange early 1909 to Peter A.B. Widener, Lynnewood Hall, Elkins Park, Pennsylvania;[6] inheritance from Estate of Peter A.B. Widener by gift through power of appointment of Joseph E. Widener, Elkins Park; gift 1942 to NGA.

[1] Gerard Hoet, Catalogus of Naamlyst van Schilderijen..., 2 vols., The Hague, 1752, 2: 482, lists in the collection of H. Verschuring "Een Oud Vrouwtje door Rembrandt. h.9d., br. 8d." The next painting listed was a pendant of an old man. Both paintings were then catalogued in the Winkler collection in 1768: Franz Wilhelm Kreuchauf, Historische Erklaerungen der Gemaelde welche Herr Gottfried Winkler in Leipzig gesammelt, Leipzig, 1798: nos. 495 and 496. Three years earlier, in 1765, the painting had been engraved in reverse by J.H. Bause, who for some reason dedicated his print to Johann Jacob Haid of Augsburg. Bause also engraved the pendant (no. 496 from Winkler's catalogue); the description of the latter work is: "Der Kopf eines betagten Mannes, mit dickaufgeschwollener Nase, kurzem Haare und Barte." This painting has disappeared but is listed in Cornelis Hofstede de Groot, A Catalogue Raisonné of the Works of the Most Eminent Dutch Painters of the Seventeenth Century..., trans. Edward G. Hawke, 8 vols., London, 1907-1927: 6(1916):no. 461. A photograph of Bause's engraving of the old man is in the NGA curatorial files.

[2] Émile Michel, Rembrandt: His Life, His Work, and His Time, Trans. Florence Simmonds, 2 vols., New York, 1894: 2:238, gives the following description of a painting in the possession of "M. Steph. Bourgeois": "Bust Portrait of a Woman, three-quarter to the front, small size. About 1640. W[ood]. 7 7/8 x 6 1/2 inches." It is possible that this painting is in fact Head of an Aged Woman, and that Rodolphe Kann obtained it from Bourgeois, but so far no direct evidence has come to light that supports this theory. Bourgeois was the father-in-law of Leo Nardus, the dealer from whom Peter A.B. Widener received the painting in 1909.

[3] Kann lent the painting to an exhibition in Amsterdam in 1898.

[4] Duveen Brothers Records, accession number 960015, Research Library, Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles: reels 38 and 39, boxes 115-118, Stock books, Paris Ledger, and Sales Book for the Kann Collection.

[5] Duveen Brothers Records, accession number 960015, Research Library, Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles: reel 39, box 117, Paris Ledger, no. 1, Kann Collection.

[6] Nardus received this painting and NGA’s Head of Saint Matthew (1942.9.58) from Kleinberger in exchange for a portrait of a lady by Hans Memling. The same two paintings, along with ten others, were sent to Widener in early 1909, as replacements for a dozen paintings Nardus had sold to and then took back from the collector, after they were deemed by art historians of the day to be modern copies of “Old Masters.”

These two transactions involving Nardus are revealed in correspondence between Widener, his lawyer, John G. Johnson, Nardus, and Nardus’ assistant, Michel van Gelder, now in the John G. Johnson Collection Archives at the Philadelphia Museum of Art (box 5, folders 5 and 6, especially a letter, Michel van Gelder to John G. Johnson, 29 January 1909). The correspondence was found, transcribed, and kindly shared with the NGA by Jonathan Lopez (letter, sent with transcriptions, 24 April 2006, to Arthur K. Wheelock, Jr., in NGA curatorial files). See also Jonathan Lopez, “‘Gross False Pretenses’: The Misdeeds of Art Dealer Leo Nardus,”_ Apollo_, ser. 2, vol. 166, no. 548 (December 2007): 80–81, fig. 9.

Associated Names

Exhibition History

1898

Rembrandt: schilderijen bijeengebracht ter gelegenheid van de inhuldiging van Hare Majesteit Koningin Wilhelmina, Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam, 1898, no. 100.

1969

Rembrandt in the National Gallery of Art [Commemorating the Tercentenary of the Artist's Death], National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., 1969, no. 8, repro., as by Rembrandt.

Bibliography

1752

Hoet, Gerard. Catalogus of naamlyst van schilderyen. 2 vols. The Hague, 1752: 2:482.

1768

Kreuchauf, Franz Wilhelm. Historische Erklaerungen der Gemaelde welche Herr Gottfried Winkler in Leipzig gesammelt. Leipzig, 1768: 201, no. 495.

1829

Smith, John. A Catalogue Raisonné of the Works of the Most Eminent Dutch, Flemish and French Painters. 9 vols. London, 1829-1842: 7(1836):182, no. 572.

1893

Michel, Émile. Rembrandt: Sa vie, son oeuvre et son temps. Paris, 1893: 563.

1894

Michel, Émile. Rembrandt: His Life, His Work, and His Time. 2 vols. Translated by Florence Simmonds. New York, 1894: 2:238.

1897

Bode, Wilhelm von, and Cornelis Hofstede de Groot. The Complete Work of Rembrandt. 8 vols. Translated by Florence Simmonds. Paris, 1897-1906: 6:26, 176, no. 472, repro., 8: 377.

1898

Hofstede de Groot, Comelis. Rembrandt: Collection des oeuvres du maître réunies, à l’occasion de l’inauguration de S. M. la Reine Wilhelmine. Exh. cat. Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam, 1898: no. 100.

1899

Bell, Malcolm. Rembrandt van Rijn and His Work. London, 1899: 82, 158.

1900

Bode, Wilhelm von. Gemälde-sammlung des Herrn Rudolf Kann in Paris. Vienna, 1900: no. 6, repro.

1904

Rosenberg, Adolf. Rembrandt: des Meisters Gemälde. Klassiker der Kunst in Gesamtausgaben 2. Stuttgart, 1904: 210, repro.

1906

Rosenberg, Adolf. Rembrandt, des Meisters Gemälde. Klassiker der Kunst in Gesamtausgaben 2. 2nd ed. Stuttgart, 1906: repro. 320.

1907

Hofstede de Groot, Cornelis. A Catalogue Raisonné of the Works of the Most Eminent Dutch Painters of the Seventeenth Century. 8 vols. Translated by Edward G. Hawke. London, 1907-1927: 6(1916):255, 258, nos. 508, 518.

Hofstede de Groot, Cornelis. Beschreibendes und kritisches Verzeichnis der Werke der hervorragendsten holländischen Maler des XVII. Jahrhunderts. 10 vols. Esslingen and Paris, 1907-1928: 6(1915):224, 227, no. 508.

Rosenberg, Adolf. The Work of Rembrandt, reproduced in over five hundred illustrations. Classics in Art 2. New York, 1907: 320, repro.

Bell, Malcolm. Rembrandt van Rijn. The great masters in painting and sculpture. London, 1907: 78, 136.

Sedelmeyer, Charles. Catalogue of Rodolphe Kann Collection. 2 vols. Paris, 1907: 1:iv, 76, no. 75, repro.

1908

Rosenberg, Adolf. Rembrandt, des Meisters Gemälde. Klassiker der Kunst in Gesamtausgaben 2. 3rd ed. Stuttgart and Berlin, 1908: repro. 440.

1909

Rosenberg, Adolf. Rembrandt: Des Meisters Gemälde. Edited by Wilhelm R. Valentiner. Klassiker der Kunst in Gesamtausgaben 2. Stuttgart and Leipzig, 1909: repro. 440.

1913

Hofstede de Groot, Cornelis, and Wilhelm R. Valentiner. Pictures in the collection of P. A. B. Widener at Lynnewood Hall, Elkins Park, Pennsylvania: Early German, Dutch & Flemish Schools. Philadelphia, 1913: unpaginated, no. 36, repro., as by Rembrandt van Rijn.

Rosenberg, Adolf. The Work of Rembrandt, reproduced in over five hundred illustrations. Classics in Art 2. Edited by Wilhelm R. Valentiner. 2nd ed. New York, 1913: repro. 440.

1914

Valentiner, Wilhelm R. The Art of the Low Countries. Translated by Mrs. Schuyler Van Rensselaer. Garden City, NY, 1914: 248, no. 74.

1921

Rosenberg, Adolf. The Work of Rembrandt. Edited by Wilhelm R. Valentiner. Classics in Art 2. 3rd ed. New York, 1921: 440, repro.

1923

Paintings in the Collection of Joseph Widener at Lynnewood Hall. Intro. by Wilhelm R. Valentiner. Elkins Park, Pennsylvania, 1923: unpaginated, repro., as by Rembrandt.

Meldrum, David S. Rembrandt’s Painting, with an Essay on His Life and Work. New York, 1923: 201, no. 383A.

1931

Valentiner, Wilhelm R. Rembrandt Paintings in America. New York, 1931: no. 131, repro.

Paintings in the Collection of Joseph Widener at Lynnewood Hall. Intro. by Wilhelm R. Valentiner. Elkins Park, Pennsylvania, 1931: 52, repro., as by Rembrandt.

1935

Bredius, Abraham. Rembrandt Schilderijen, 630 Afbeeldingen. Utrecht, 1935: no. 392, repro.

Bredius, Abraham. Rembrandt Gemälde, 630 Abbildungen. Vienna, 1935: no. 392, repro.

1936

Bredius, Abraham. The Paintings of Rembrandt. New York, 1936: no. 392, repro.

1942

National Gallery of Art. Works of art from the Widener collection. Washington, 1942: 6, as by Rembrandt van Ryn.

Bredius, Abraham. The Paintings of Rembrandt. 2 vols. Translated by John Byam Shaw. Oxford, 1942: 1:no. 392; 2:repro.

1948

National Gallery of Art. Paintings and Sculpture from the Widener Collection. Washington, 1948: 42, repro., as by Rembrandt van Ryn.

1957

Duveen, James Henry. The Rise of the House of Duveen. New York, 1957: 234.

1959

National Gallery of Art. Paintings and Sculpture from the Widener Collection. Reprint. Washington, DC, 1959: 42, repro., as by Rembrandt.

1963

Walker, John. National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. New York, 1963 (reprinted 1964 in French, German, and Spanish): 313, repro., as by Rembrandt van Rijn.

1965

National Gallery of Art. Summary Catalogue of European Paintings and Sculpture. Washington, 1965: 110, as by Rembrandt.

1966

Bauch, Kurt. Rembrandt Gemälde. Berlin, 1966: 15, no. 273, repro.

1968

National Gallery of Art. European Paintings and Sculpture, Illustrations. Washington, 1968: 98, repro.

1969

Bredius, Abraham. Rembrandt: The Complete Edition of the Paintings. Revised by Horst Gerson. 3rd ed. London, 1969: repro. 301, 581, no. 392.

National Gallery of Art. Rembrandt in the National Gallery of Art: Commemorating the tercentenary of the artist's death. Exh. cat. National Gallery of Art, Washington, 1969: 18, no. 8, repro.

1975

National Gallery of Art. European paintings: An Illustrated Summary Catalogue. Washington, 1975: 288, repro., as by Rembrandt.

1976

Fowles, Edward. Memories of Duveen Brothers. London, 1976: 52, 205.

Hoet, Gerard. Catalogus of naamlyst van schilderyen. 3 vols. Reprint of 1752 ed. with supplement by Pieter Terwesten, 1770. Soest, 1976: 2:482.

1985

National Gallery of Art. European Paintings: An Illustrated Catalogue. Washington, 1985: 334, repro.

1995

Wheelock, Arthur K., Jr. Dutch Paintings of the Seventeenth Century. The Collections of the National Gallery of Art Systematic Catalogue. Washington, 1995: 330-333, color repro. 331.

2002

Quodbach, Esmée. "The Last of the American Versailles: The Widener Collection at Lynnewood Hall." Simiolus 29, no. 1/2 (2002): 71.

2007

Lopez, Jonathan. "‘Gross False Pretenses’: The Misdeeds of Art Dealer Leo Nardus." Apollo ser. 2, 166, no. 548 (December 2007): 80-81, fig. 9.

Inscriptions

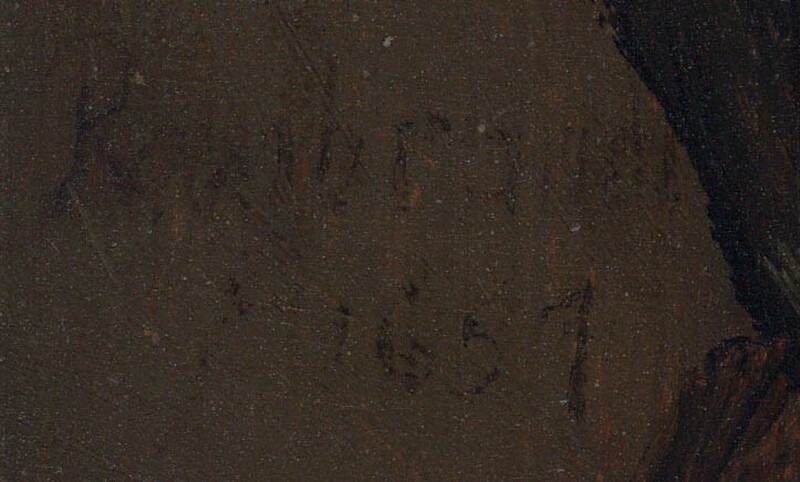

center left by a later hand: Rembrandt / f.1657

Wikidata ID

Q20177386