The Circumcision

1661

Rembrandt van Rijn

Artist, Dutch, 1606 - 1669

After learning the fundamentals of drawing and painting in his native Leiden, Rembrandt van Rijn went to Amsterdam in 1624 to study for six months with Pieter Lastman (1583–1633), a famous history painter. Upon completion of his training Rembrandt returned to Leiden. Around 1632 he moved to Amsterdam, quickly establishing himself as the town’s leading artist. He received many commissions for portraits and attracted a number of students who came to learn his method of painting.

Only the Gospel of Luke, 2:15–22, mentions the circumcision of Christ: "the shepherds said one to another, Let us now go even unto Bethlehem.... And they came with haste, and found Mary and Joseph, and the babe lying in a manger.... And when eight days were accomplished for the circumcising of the child, his name was called Jesus." This cursory reference to this significant event in the early childhood of Christ allowed artists throughout history wide latitude in the way they represented the circumcision. The predominant Dutch pictorial tradition was to depict the ceremony as occurring in the Temple, but in this beautifully evocative painting Rembrandt places the scene in front of the stable. In this innovative composition, Mary, rather than Joseph or another male figure, tenderly holds her son in her lap in front of the ladder of the stable, just as she will cradle his corpse some thirty-three years later near a ladder leaning against the cross. In this way Rembrandt suggests the fundamental association between the circumcision and Christ's final shedding of blood at his Crucifixion. Onlookers crowd around the scribe who records the name of the Child in a large book.

Iconographic, compositional, and documentary evidence all point strongly to Rembrandt's authorship. The fact that a dealer, who knew Rembrandt's work well and who was in the midst of complex financial arrangements with him, paid a substantial amount of money for this painting makes it virtually certain that The Circumcision was executed by the master himself.

West Building Main Floor, Gallery 51

Artwork overview

-

Medium

oil on canvas

-

Credit Line

-

Dimensions

overall: 56.5 x 75 cm (22 1/4 x 29 1/2 in.)

framed: 81.3 x 99 x 8.2 cm (32 x 39 x 3 1/4 in.) -

Accession Number

1942.9.60

More About this Artwork

Artwork history & notes

Provenance

Lodewijck van Ludick [1607-1669], Amsterdam, by 1662.[1] Probably Ferdinand Bol [1616-1680], by 1669.[2] Probably Isaak van den Blooken, The Netherlands, by 1707; (his sale, Jan Pietersz. Zomer, Amsterdam, 11 May 1707, no. 1). Duke of Ancaster; (his sale, March 1724, no.18); Andrew Hay; (his sale, Cock, London, 14-15 February 1745, no. 47);[3] John Spencer, 1st earl Spencer [1734-1783], Althorp, Northamptonshire; by inheritance through the earls Spencer to John Poyntz, 5th earl Spencer [1835-1910], Althorp;[4] (Arthur J. Sulley & Co., London); Peter A.B. Widener, Lynnewood Hall, Elkins Park, Pennsylvania, by 1912; inheritance from Estate of Peter A.B. Widener by gift through power of appointment of Joseph E. Widener, Elkins Park, Pennsylvania; gift 1942 to NGA.

[1] On 18 August 1662 Rembrandt and Van Ludick drew up a contract to address the artist's debts, in the second part of which is revealed that sometime earlier Rembrandt had sold the painting to Van Ludick. See: Walter L. Strauss and Marjon van der Meulen, The Rembrandt Documents, New York, 1979: doc. 1662/6, 499–502; Paul Crenshaw, Rembrandt's bankruptcy: the artist, his patrons, and the art market in the seventeenth-century, Cambridge and New York, 2006: 30, 84, 107, 179 n. 200.

[2] Albert Blankert, Ferdinand Bol (1616-1680): Rembrandt's Pupil, translated by Ina Rike, Doornspijk, 1982: 76-77, no. 14 in an inventory of 8 October 1669.

[3] For the Ancaster and Hay sales, see Frank Simpson, "Dutch Paintings in England before 1760," The Burlington Magazine 95 (January 1953): 41. The Duke of Ancaster who sold the painting in 1724 would have been Peregrine Bertie, 2nd duke of Ancaster and Kesteven (1686-1742); it is possible he was selling paintings that had been in the collection of his father, Robert Bertie, the 1st duke, who had died the year before (he lived 1660-1723).

[4] The painting is listed in Spencer collection catalogues and inventories in 1746, 1802, and 1822, and was lent by the earls Spencer to exhibitions in 1868, 1898, and 1899.

Associated Names

Exhibition History

1868

National Exhibition of Works of Art, Leeds Art Gallery, England, 1868, no. 735.

1898

Rembrandt: Schilderijen Bijeengebracht ter Gelegenheid van de Inhuldiging van Hare Majesteit Koningin Wilhelmina, Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam, 1898, no. 115.

1899

Exhibition of Works by Rembrandt. Winter Exhibition, Royal Academy of Arts, London, 1899, no. 5.

1969

Rembrandt in the National Gallery of Art [Commemorating the Tercentenary of the Artist's Death], National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., 1969, no. 22, repro.

1986

Rembrandt and the Bible, Sogo Museum of Art, Yokohoma; Fukuoka Art Museum; National Museum of Modern Art, Kyoto, 1986-1987, no. 11 (shown only in Fukuoka and Kyoto, 1987).

1998

A Collector's Cabinet, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., 1998, no. 46, repro.

2004

Rembrandt, Albertina, Vienna, 2004, no. 134, repro.

2006

Rembrandt - Quest of a Genius [Rembrandt - Zoektocht van een Genie] [Rembrandt - Genie auf der Suche], Museum Het Rembrandthuis, Amsterdam; Kulturforum, Berlin, 2006, fig. 209 in Amsterdam catalogue (not in Berlin catalogue).

2008

Rembrandt: Pintor de Historias [Rembrandt: Painter of History], Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid, 2008-2009, no. 39, repro.

2017

Ferdinand Bol: het huis, de collectie, de kunstenaar [Ferdinand Bol: the house, the collection, the artist], Museum Van Loon, Amsterdam, 2017-2018, no. 22, repro.

2018

Rembrandt: Painter as Printmaker, Denver Art Museum, 2018-2019, no. 99, repro.

Bibliography

1829

Smith, John. A Catalogue Raisonné of the Works of the Most Eminent Dutch, Flemish and French Painters. 9 vols. London, 1829-1842: 7(1836):xxiii, 28, no. 69.

1838

Waagen, Gustav Friedrich. Works of Art and Artists in England. 3 vols. Translated by H. E. Lloyd. London, 1838: 3:336.

1854

Waagen, Gustav Friedrich. Treasures of Art in Great Britain: Being an Account of the Chief Collections of Paintings, Drawings, Sculptures, Illuminated Mss.. 3 vols. Translated by Elizabeth Rigby Eastlake. London, 1854: 3:459.

1868

Vosmaer, Carel. Rembrandt Harmens van Rijn, sa vie et ses œuvres. The Hague, 1868: 311, 496.

1877

Vosmaer, Carel. Rembrandt Harmens van Rijn: sa vie et ses oeuvres. 2nd ed. The Hague, 1877: 361, 562.

1879

Mollett, John W. Rembrandt. Illustrated biographies of the great artists. London, 1879: 73.

1883

Dutuit, Eugène. L'oeuvre complet de Rembrandt: catalogue raisonné de toutes les estampes du maître accompagné de leur reproduction en facsimili de la granden des originaux. Paris, 1883: 48, no. 53.

Bode, Wilhelm von. Studien zur Geschichte der holländischen Malerei. Braunschweig, 1883: 525, 578, no. 137.

1884

Roever, Nicolaas de "Rembrandt: Bijdragen tot de geschiedenis van zijn laatste levensjaren." Oud Holland 2 (1884): 81-105.

1885

Dutuit, Eugène. Tableaux et dessins de Rembrandt: catalogue historique et descriptif; supplément à l'Oeuvre complet de Rembrandt. Paris, 1885: 48, 59, no. 53.

1893

Michel, Émile. Rembrandt: Sa vie, son oeuvre et son temps. Paris, 1893: 462-463, 555.

1894

Michel, Émile. Rembrandt: His Life, His Work, and His Time. 2 vols. Translated by Florence Simmonds. New York, 1894: 2:237.

1897

Bode, Wilhelm von, and Cornelis Hofstede de Groot. The Complete Work of Rembrandt. 8 vols. Translated by Florence Simmonds. Paris, 1897-1906: 7:13, 98-99, no. 518, repro.

1898

Hofstede de Groot, Comelis. Rembrandt: Collection des oeuvres du maître réunies, à l’occasion de l’inauguration de S. M. la Reine Wilhelmine. Exh. cat. Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam, 1898: no. 115.

1899

Hofstede de Groot, Cornelis. "Die Rembrandt-Ausstellungen zu Amsterdam (September–October 1898) und zu London (January–March 1899)." Repertorium für Kunstwissenschaft 22 (1899): 163, no. 115.

Bell, Malcolm. Rembrandt van Rijn and His Work. London, 1899: 85.

Royal Academy of Arts. Exhibition of works by Rembrandt. Exh. cat. Royal Academy of Arts, London, 1899: 10, no. 5.

1904

Rosenberg, Adolf. Rembrandt: des Meisters Gemälde. Klassiker der Kunst in Gesamtausgaben 2. Stuttgart, 1904: 236, 264, repro.

1906

Rosenberg, Adolf. Rembrandt, des Meisters Gemälde. Klassiker der Kunst in Gesamtausgaben 2. 2nd ed. Stuttgart, 1906: repro. 366, 405, 418-419, 430.

Hofstede de Groot, Cornelis. Die Urkunden über Rembrandt (1575-1721). Quellenstudien zur holländischen Kunstgeschichte 3. The Hague, 1906: 302.

1907

Brown, Gerard Baldwin. Rembrandt: A Study of His Life and Work. London, 1907: 211.

Hofstede de Groot, Cornelis. A Catalogue Raisonné of the Works of the Most Eminent Dutch Painters of the Seventeenth Century. 8 vols. Translated by Edward G. Hawke. London, 1907-1927: 6(1916):68, no. 82.

Bell, Malcolm. Rembrandt van Rijn. The great masters in painting and sculpture. London, 1907: 81, 123.

Rosenberg, Adolf. The Work of Rembrandt, reproduced in over five hundred illustrations. Classics in Art 2. New York, 1907: 366, repro.

1908

Rosenberg, Adolf. Rembrandt, des Meisters Gemälde. Klassiker der Kunst in Gesamtausgaben 2. 3rd ed. Stuttgart and Berlin, 1908: repro. 465, 564, 579, 582, 595.

1909

Rosenberg, Adolf. Rembrandt: Des Meisters Gemälde. Edited by Wilhelm R. Valentiner. Klassiker der Kunst in Gesamtausgaben 2. Stuttgart and Leipzig, 1909: repro. 465, 564, 579, 582, 595.

1913

Hofstede de Groot, Cornelis, and Wilhelm R. Valentiner. Pictures in the collection of P. A. B. Widener at Lynnewood Hall, Elkins Park, Pennsylvania: Early German, Dutch & Flemish Schools. Philadelphia, 1913: unpaginated, repro.

Rosenberg, Adolf. The Work of Rembrandt, reproduced in over five hundred illustrations. Classics in Art 2. Edited by Wilhelm R. Valentiner. 2nd ed. New York, 1913: repro. 465.

1914

Valentiner, Wilhelm R. The Art of the Low Countries. Translated by Mrs. Schuyler Van Rensselaer. Garden City, NY, 1914: 249, no. 87.

1921

Valentiner, Wilhelm R. Rembrandt: wiedergefundene Gemälde (1910-1922). Klassiker der Kunst in Gesamtausgaben 27. Stuttgart and Berlin, 1921: 465, repro.

Rosenberg, Adolf. The Work of Rembrandt. Edited by Wilhelm R. Valentiner. Classics in Art 2. 3rd ed. New York, 1921: 465, repro.

1923

Meldrum, David S. Rembrandt’s Painting, with an Essay on His Life and Work. New York, 1923: 64, 107-108, 202, pl. 415.

Paintings in the Collection of Joseph Widener at Lynnewood Hall. Intro. by Wilhelm R. Valentiner. Elkins Park, Pennsylvania, 1923: unpaginated, repro.

Van Dyke, John C. Rembrandt and His School. New York, 1923: 144.

1930

Valentiner, Wilhelm R. "Important Rembrandts in American Collections." Art News 28, no. 30 (26 April 1930): 3-84, repro.

1931

Paintings in the Collection of Joseph Widener at Lynnewood Hall. Intro. by Wilhelm R. Valentiner. Elkins Park, Pennsylvania, 1931: 58, repro.

Valentiner, Wilhelm R. Rembrandt Paintings in America. New York, 1931: no. 150, repro.

1935

Bredius, Abraham. Rembrandt Schilderijen, 630 Afbeeldingen. Utrecht, 1935: no. 596, repro.

Bredius, Abraham. Rembrandt Gemälde, 630 Abbildungen. Vienna, 1935: no. 596, repro.

1936

Bredius, Abraham. The Paintings of Rembrandt. New York, 1936: no. 596, repro.

1938

Waldmann, Emil. "Die Sammlung Widener." Pantheon 22 (November 1938): 342.

1942

Mather, Frank Jewett. "The Widener Collection at Washington." Magazine of Art 35 (October 1942): 198, repro.

National Gallery of Art. Works of art from the Widener collection. Washington, 1942: 6, no. 656.

Bredius, Abraham. The Paintings of Rembrandt. 2 vols. Translated by John Byam Shaw. Oxford, 1942: 1:no. 596; 2:repro.

1948

National Gallery of Art. Paintings and Sculpture from the Widener Collection. Washington, 1948: 47, repro.

1953

Simpson, Frank. "Dutch Paintings in England before 1760." The Burlington Magazine 95, no. 599 (January 1953): 39-42.

1954

Münz, Ludwig. Rembrandt Harmenszoon van Rijn. The Library of Great Painters. New York, 1954: 146-147, repro.

1959

National Gallery of Art. Paintings and Sculpture from the Widener Collection. Reprint. Washington, DC, 1959: 48, repro.

1963

Walker, John. National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. New York, 1963: 313, repro.

1965

National Gallery of Art. Summary Catalogue of European Paintings and Sculpture. Washington, 1965: 110.

1966

Bauch, Kurt. Rembrandt Gemälde. Berlin, 1966: 6-7, no. 93, repro.

Schiller, Gertrud. Ikonographie der christlichen Kunst. 6 vols. Gütersloh, 1966-1990: 1:100.

1968

Gerson, Horst. Rembrandt Paintings. Amsterdam, 1968: 132, 134, 154, 410, 416, repro., 501-502, no. 350.

National Gallery of Art. European Paintings and Sculpture, Illustrations. Washington, 1968: 99, repro.

1969

Bredius, Abraham. Rembrandt: The Complete Edition of the Paintings. Revised by Horst Gerson. 3rd ed. London, 1969: repro. 500, 611, no. 596.

National Gallery of Art. Rembrandt in the National Gallery of Art: Commemorating the tercentenary of the artist's death. Exh. cat. National Gallery of Art, Washington, 1969: 6, 32, no. 22, repro.

1971

Schiller, Gertrud. Iconography of Christian art. 2 vols. Translated by Janet Seligman. London, 1971: 1:90.

1974

Garlick, Kenneth. "A Catalogue of Pictures at Althorp." Walpole Society 45 (1974-1976): 117-124.

1975

National Gallery of Art. European paintings: An Illustrated Summary Catalogue. Washington, 1975: 286, repro.

Walker, John. National Gallery of Art, Washington. New York, 1975: 282, no. 373, color repro.

1978

Esteban, Claude, Jean Rudel, and Simon Monneret. Rembrandt. Paris, 1978: 112-113, color repro.

1979

Keller, Ulrich. "Knechtschaft und Freiheit: ein neutestamentliches Thema bei Rembrandt." Jahrbuch der Hamburger Kunstsammlungen 24 (1979): 77-112, color repro.

Strauss, Walter L., and Marjon van der Meulen. The Rembrandt Documents. New York, 1979: 480, 499-500.

1980

Hoekstra, Hidda. Rembrandt en de bijbel. Utrecht, 1980: 27, repro.

1981

Tümpel, Christian. "Rembrandt, die Bildtradition und der Text." In Ars Auro Prior: Studia Ioanni di Bialostocki Sexagenario Bicata. Warsaw, 1981: 429-434.

1984

Schwartz, Gary. Rembrandt: Zijn leven, zijn schilderijen. Maarssen, 1984: 324, no. 376, repro.

Walker, John. National Gallery of Art, Washington. Rev. ed. New York, 1984: 283, no. 367, color repro., as by Rembrandt van Ryn.

Münz, Ludwig. Rembrandt. Revised ed. London, 1984: 112-113, repro.

1985

National Gallery of Art. European Paintings: An Illustrated Catalogue. Washington, 1985: 331, repro.

Schwartz, Gary. Rembrandt: His Life, His Paintings. New York, 1985: 324, 330, no. 376, repro.

1986

Guillaud, Jacqueline, and Maurice Guillaud. Rembrandt: das Bild des Menschen. Translated by Renate Renner. Stuttgart, 1986: 554-555, color repro.

Senzoku, Nobuyuki. Renburanto, Kyosho to sono shuhen [Rembrandt and the Bible]. Exh. cat. Sogo Museum of Art, Yokohama; Fukuoka Art Museum; Kyoto National Museum of Modern Art. Tokyo, 1986: 65, no. 11, color repro.

Sutton, Peter C. A Guide to Dutch Art in America. Washington and Grand Rapids, 1986: 312.

Tümpel, Christian. Rembrandt. Translated by Jacques and Jean Duvernet, Léon Karlson, and Patrick Grilli. Paris, 1986: repro. 355, 420, no. A12.

Guillaud, Jacqueline, and Maurice Guillaud. Rembrandt, the human form and spirit. Translated by Suzanne Boorsch et al. New York, 1986: nos. 554-555, color repro.

1988

Pears, Iain. The Discovery of Painting: The Growth of Interest in the Arts in England, 1680–1768. Studies in British Art. New Haven, 1988: 83, repro.

1995

Wheelock, Arthur K., Jr. Dutch Paintings of the Seventeenth Century. The Collections of the National Gallery of Art Systematic Catalogue. Washington, 1995: 270-276, color repro. 271.

1998

Wheelock, Arthur K., Jr. A Collector's Cabinet. Exh. cat. National Gallery of Art, Washington, 1998: 67, no. 46, repro.

2003

Waagen, Gustav Friedrich. Treasures of Art in Great Britain. Translated by Elizabeth Rigby Eastlake. Facsimile edition of London 1854. London, 2003: 3:459.

2004

Schröder, Klaus Albrecht, and Marian Bisanz Prakken. Rembrandt. Edition Minerva. Exh. cat. Graphische Sammlung Albertina, Vienna. Wolfratshausen, 2004: 284-285, no. 134, repro.

2006

Wetering, Ernst van de. Rembrandt: Quest of a genius. Edited by Bob van den Boogert. Exh. cat. Museum Het Rembrandthuis, Amsterdam; Gemäldegalerie, Berlin. Zwolle, 2006: fig. 209, 184.

Crenshaw, Paul. Rembrandt's bankruptcy: the artist, his patrons, and the art market in seventeenth-century Netherlands. Cambridge and New York, 2006: 84, 107, 179 n. 200.

2008

De Witt, David. The Bader Collection Dutch and Flemish paintings. Agnes Etherington Art Centre Catalogues. Kingston, Ontario, 2008: 268-269, repro. 268.

Vergara, Alexander. Rembrandt, pintor de historias. Exh. cat. Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid, 2008: no. 39, 210-212.

2014

Bikker, Jonathan, and Gregor J.M. Weber. Rembrandt: The Late Works. Exh. cat. National Gallery, London; Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam. London, 2014: 30, fig. 10, 272 nn. 61, 62.

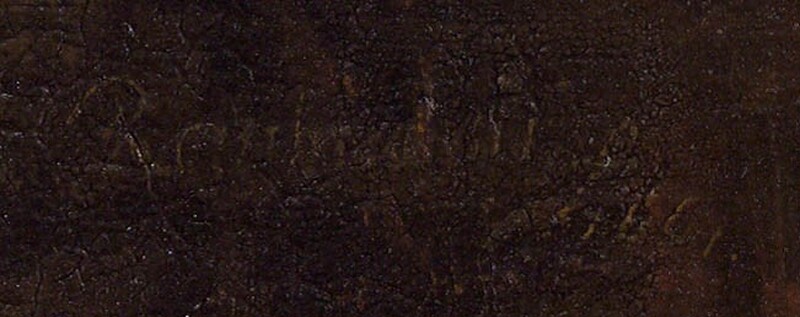

Inscriptions

lower right: Rembrandt. f. 1661

Wikidata ID

Q20177576